A Trojan Horse for Change

A former trader decides to start a company and build software for other professional investors. His startup marches promptly to $100mn in revenue and sustains double-digit growth for years. It has a long future, and has already changed the market forever.

The startup creates a new type of synthesis layer—an aggregation of systematic channels, unstructured documents, and proprietary sources. It automates analysts’ undifferentiated heavy lifting. No more browsing long reports or chasing esoteric data. And the product is much better than those of established competitors, whose tools and data are hopelessly siloed. It’s more interactive and plugs into diligence, dealmaking, and trading. Tedious tasks shrink from hours to seconds. Firms make pricing decisions with a speed and completeness never before possible. In time, these improvements to the old ways enable new investing strategies and new types of investment firms.

This is what the Bloomberg Terminal did in the bond and public equity markets in the 1980s. And it foreshadows why we’re underestimating how AI will change private markets.

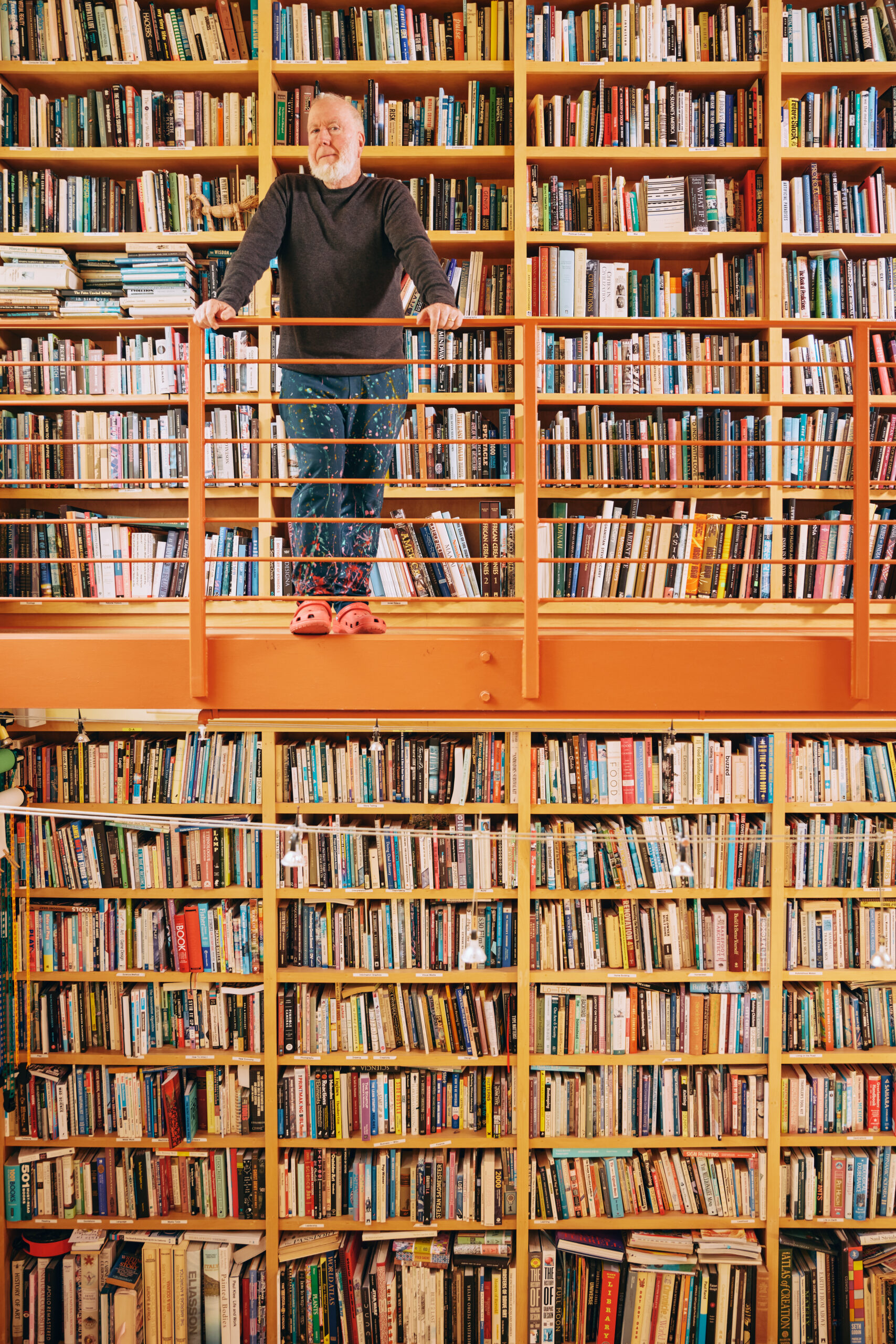

Bob Hamill understands how technology transforms investing. He’s spent nearly 35 years leading investment teams at some of Wall Street’s most well-known firms—Drexel Burnham Lambert, Citi, J.P. Morgan, Lehman Brothers, and Jefferies. In this time, he successfully navigated the rise of the terminal, electronic trading, and the internet. Over lunch, he told us how those shifts ultimately reshaped the market in surprising ways.

In 1984, the year the Bloomberg Terminal launched, Hamill was just starting his career in investment banking at EF Hutton. He vividly remembers how work was done with paper spreadsheets, white-out, and the HP 12c, a checkbook-sized calculator that could display 10 digits. Lucky teams shared a single Quotron, an electronic version of a ticker tape machine. “You would fill out the spreadsheets and do everything by hand,” he explained. “You would take it to the word processing department and a couple hours later it would come out. And the key thing is you had to be proofreading like crazy because they were literally entering the stuff in. Your desk had a ton of pens and pages of paper and white-out and erasers. No TVs, no screens.”

striegel, Minderbinder

The Quotron, HP 12c calculator. Not pictured: the pencil and paper required to finalize trade calculations.

Bloomberg meant alpha for early adopters. It allowed traders to access real-time data on their investments and quickly compute trade information, all using the same platform. It easily surpassed existing bond math calculators by summarizing extra information like a bond’s terms, company description, and holder list. This conferred an edge over traders relying on manual workflows and fragmented systems. “You didn’t need to calculate bond prices or look at prospectuses. You pretty much took the summary information for granted,” Hamill explained. “Getting that Bloomberg box was pretty cool. It was a status symbol.”

These advantages quickly became table stakes. By 1986, Bloomberg was selling 10x more terminals than in 1984. By 1996, it was selling 10x more than that[1] [2]. Early-adopter alpha vanished.

In the end, Bloomberg’s knowledge-work automation was a Trojan horse for far greater change. It made markets more competitive, but also enabled new types of investing, like programmatic, quantitative strategies and technology-native investment firms. Hamill also explained that it helped facilitate the rise of indexing, noting that “there was basically no passive money in the late 80s, early 90s.” Jack Bogle deserves credit for creating the investor demand, but it was Bloomberg that made it cheap to build, rebalance, and distribute indexes like the iconic Lehman Aggregate (created in 1986, now owned by Bloomberg itself). Today, almost half of US investment firm holdings are in indexes.

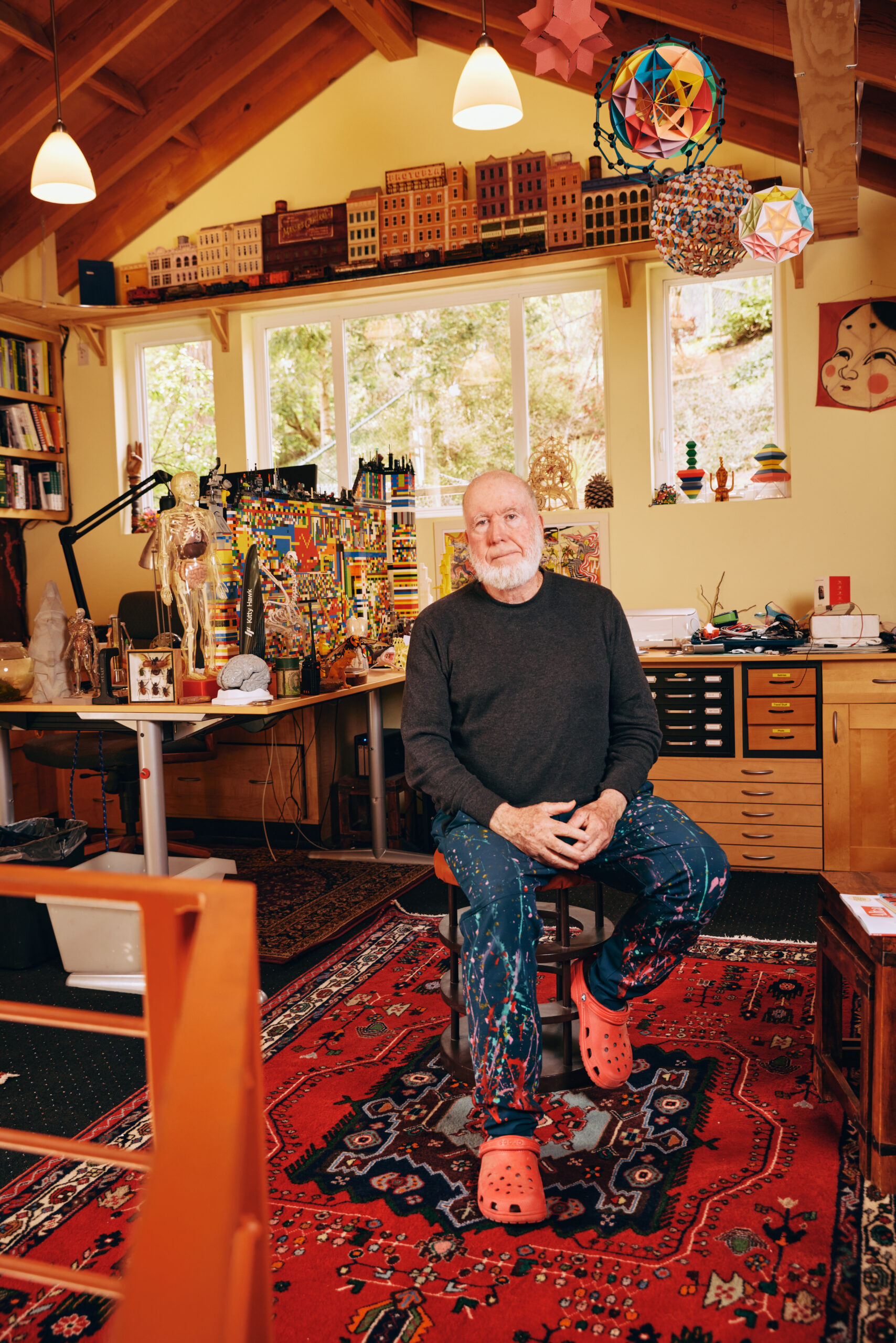

TOM TRACY PHOTOGRAPHY

A 1980s bond trading floor. Find paper spreadsheets, newspapers, spiral-bound pitch books, Monroe bond math calculators, Quotron monitors, and phone banks for direct lines.

Bloomberg was a key catalyst for spiraling changes in the bond and equity markets. We think AI will drive a similar pattern of change in private equity and venture capital today. Firms working against the backdrop of more crowded and competitive markets will readily adopt AI for operational efficiency. As this technology becomes ubiquitous, it will create opportunities to invest in completely new ways.

In a world where every private markets investor relies on AI, we believe that the enduring moats of relationships, data, and operational excellence will matter even more. Cheap data aggregation means only truly proprietary data will provide an edge. Democratized information means firms need unparalleled access and genuine trust to win the best deals. Maximizing operating leverage requires systems that can adjust to conditions in real time.

We explore these themes through conversations with the best founders building in this space today.

A $100bn Prize for AI in Finance

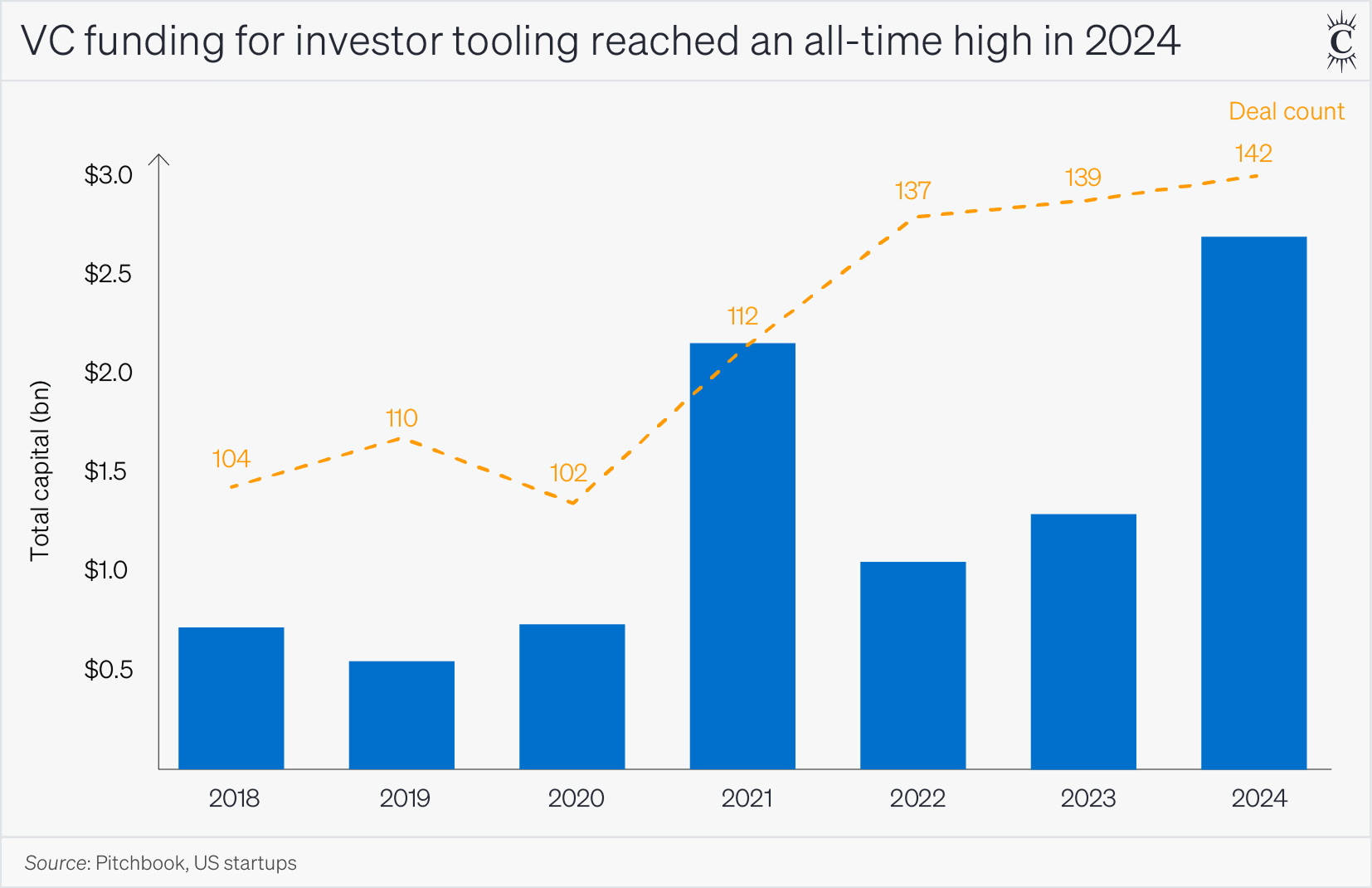

The artificial intelligence stack for investors is gaining momentum, fast.

Gabe Stengel is the Founder of Rogo, an AI-powered financial research platform established in 2021 for deal teams in public and private markets. It’s part of a wave of new companies changing how investors operate, and Stengel has seen the rapid embrace of AI for everything, from memo summarization to sourcing automation, up close. He thinks the biggest impacts of AI are yet to be felt.

“The things that would have required a special financial workflow two years ago, like benchmarking or comps, are now able to be done by systems like Rogo.” Eventually, “we’re going to do everything. We’re going to do the modeling. We’re going to do investment committee memos. We’re going to write that outbound email for you. We’re going to update your CRM when you speak with a company. Really, we’re going to replace and augment everything you do.”

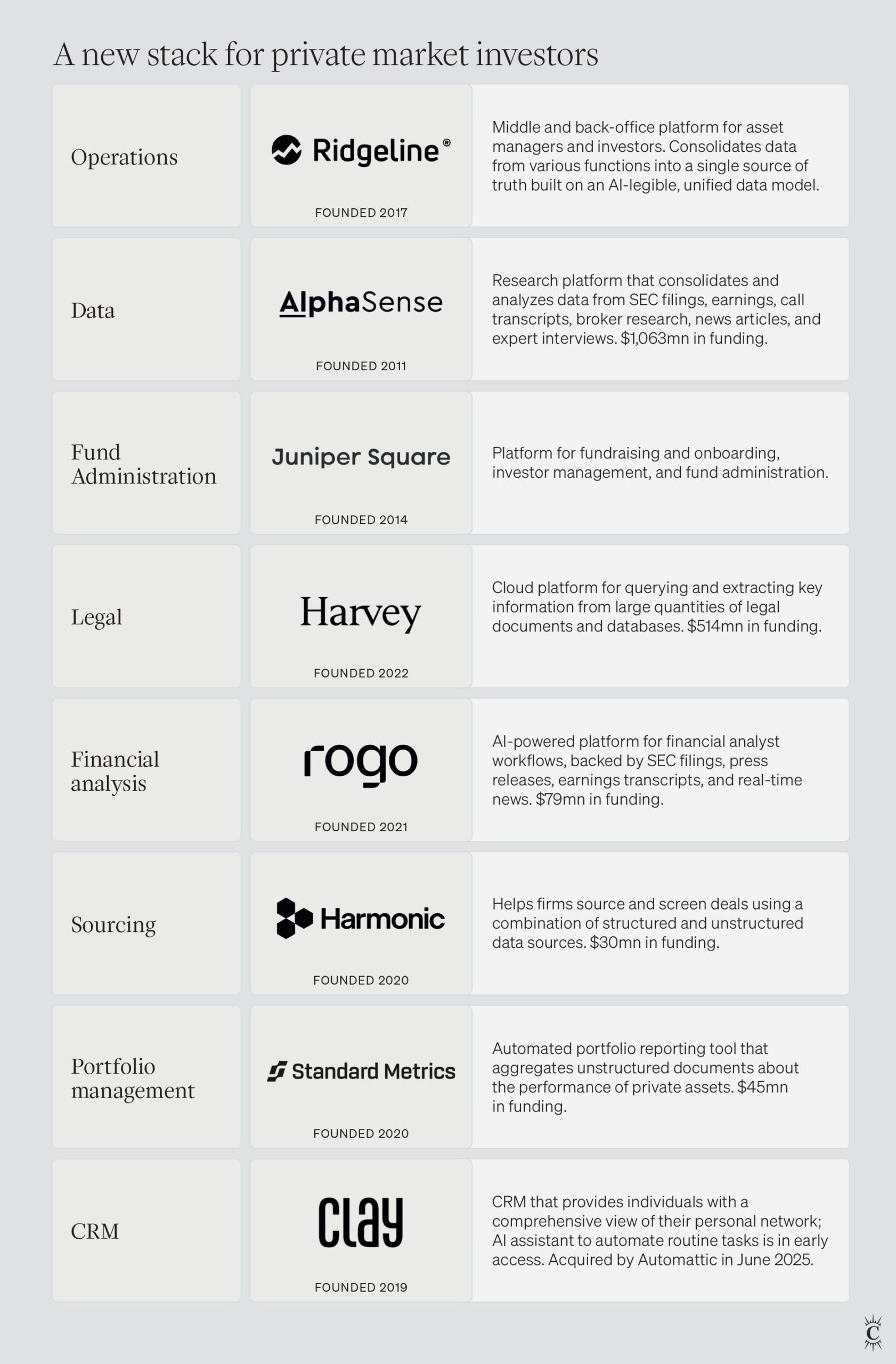

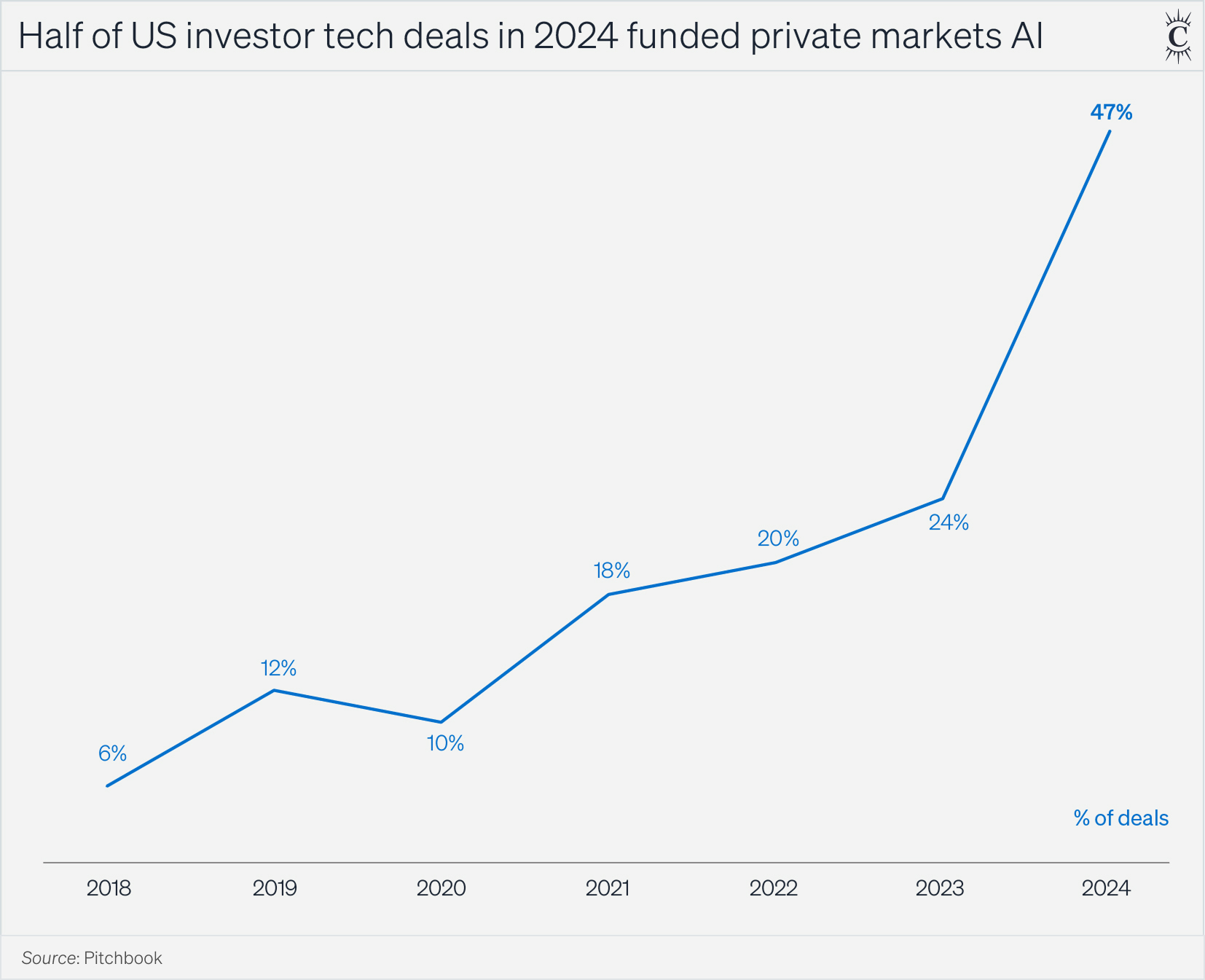

Startup activity supports Stengel’s take that even more transformative use cases for AI will emerge in the coming years. Early-stage investors are jockeying for exposure—in the past year alone, VCs have put over $2.5bn into 100+ US startups building tooling for investment firms. This is still a relatively small share of overall VC funding, representing less than 1% of the nearly $400bn deployed in 2024, but is 5x more than the pre-LLM baseline. Nearly half of these companies are currently positioning themselves as AI companies, and many more incorporate AI into their product in some form.

Taken together, the startups being funded cover virtually every part of a firm’s operations—a new, AI-powered stack for investors. The products they are building allow investors to integrate internal data to accelerate deal sourcing, due diligence, and internal communications. They are often competing with incumbents—S&P Global, SS&C, and more—that are also racing to deploy generative AI in their product offerings.

Many firms we’ve met aren’t waiting around for products to come to market; they’ve developed their own platforms on top of models from the major providers. These internal platforms range from organizational and summarization tools to end-to-end investment diligence applications. Some of these efforts have already been spun out—Seattle-based Finpilot traces its roots to internal tools built at Euclidean Technologies, a quantitative investment firm. There is precedent for this motion: BlackRock’s Aladdin® started as an internal risk management software project, and is now the platform of choice for the world’s largest asset managers.

We don’t see these trends slowing down. There’s still ample white space for companies and firms to build products, including in ways that slice the market differently than the traditional operational verticals we highlighted in our market map. For example, paid expert network calls are too expensive for many of the smaller firms we’ve met. However, voice AI has made tremendous strides over the past few years, and is approaching quality and latency indistinguishable from actual humans. A future expert network product could use AI across the entire product surface—to ingest requirements from firms, source the right experts, conduct calls at the level of quality of an analyst-mediated conversation, and synthesize results. In doing so, it could significantly lower the overhead and cost required to access expert insights. Startups like Listen Labs and Bridgetown Research are ones to watch in this space.

Another challenge we expect AI products to attack is that investor telemetry is underutilized in private markets like venture and private equity. Pitchbook and Cambridge Associates publish data on capital flows, vertical-specific funding dynamics, investor hiring, and manager performance, but are largely oriented around looking up specific data or high-level quarterly reports of aggregate statistics. We think that AI presents an opportunity for products that help investors tailor reference points to understand their performance across many dimensions. They could contextualize their deal flow within broader capital flow patterns to understand whether they are early or late to funding trends. The startup Vantager is attacking this from the limited partner side, using AI to normalize general partner reporting and provide reference sets to help LPs diligence managers.

We also see an opportunity for products that enable firms to get more out of their own data. The principal shortcoming we’ve experienced with off-the-shelf tools like Gemini or OpenAI Deep Research is that we can’t inject our proprietary data (often the most valuable and insightful) into the tools’ analyses. A product that allows firms to easily integrate and structure their disparate data—like decks, emails, and call transcripts—with minimal friction could supercharge research by making all the firm’s data legible to AI.

Labor automation is the wedge

While the emerging AI stack for investors covers a laundry list of investing firm processes, every product in it ultimately leverages AI for the same task: aggregation and transformation of data from one format to another. Think extraction of financial data from an earnings report transcript into an Excel workbook, the automatic identification and replacement of the ‘usual’ clauses during redlining, or summarization of a company’s data room during diligence. In all cases, humans are being replaced as the translation layer between documents and data. Most of these tasks have historically been impossible to automate with rigid, rules-based software, and manual work was the only viable solution.

As such, the immediate prize these companies are chasing is the pool of labor largely populated by highly trained professionals like analysts, associates, lawyers, and operations staff. This is a large market, even when crudely measured via direct labor costs. There are over 450,000 financial analysts in the US alone, representing a ~$100bn+ labor TAM.[3] This number increases into the hundreds of billions globally, especially when supporting infrastructure and other roles are included in the tally.

We don’t think the full value of the market can be consumed by AI, but we do believe AI tooling can capture a significant portion of it. For most investment diligence workflows, upstream work to find and prepare data, and downstream work to synthesize and report results, is often as time consuming as any analysis. Automating these things frees more time for investment teams or operations staff to focus on the places that demand intuition and creativity.

We’ve seen the benefits of this ourselves. At Positive Sum, we’ve built an in-house AI research platform called Hubble, and use it to accelerate our understanding of markets and companies. Hubble has full deal context—it automatically aggregates everything from our external sources, call transcripts, company decks, proprietary data, and internal discussions. This up-to-date context means the system is a valuable copilot across the end-to-end investment process: we use it to generate subject-matter primers ahead of our first call with a founder, flag risks in a company deck, measure how our firm’s perception of a company changes over time, and even draft full investment memos. Some of these tasks, when offloaded to Hubble, save up to eight hours of rote work, and over the course of a typical diligence process, Hubble can save days’ worth of effort.

Private markets are the last mile

The $20tn managed by private markets investors—especially in venture and private equity—will arguably be the biggest beneficiary of this new way of operating. These firms run on varied documents, not orderly data feeds. Virtual data rooms are stocked with lengthy PDFs and slide decks. Bespoke spreadsheets are the currency of the realm. There’s no Sarbanes-Oxley driving regular and standardized reporting for firms to consume.

There are good reasons why the current status quo exists. Historically, it simply didn’t make sense to invest in automation because of relatively low deal volume. Transactions are typically between a company’s owners and investors, perhaps through an investment bank. A PE or VC firm might ‘trade’ a dozen times a year and hold an asset for a decade; many hedge funds trade a dozen times per second. These deals are also relatively large—measured in the millions or billions of dollars. Deploying human capital to carry out diligence for these deals is a worthwhile investment.

“Private equity is the last mile” for investment workflow automation, Techstars-backed Founder Lydia Ofori, CFA, CAIA says. She’s spent two decades working across both private and public markets investment firms, deploying a wide range of strategies, and has seen both the opportunities—and challenges—for automation up close. Now, her startup Plainr aims to let private markets investors get more out of their internal and external data via AI. Ofori sees the opportunity as a lattice of new models, first principles engineering, and a shift from static, manual processes to live ones. “I do believe that if a modicum of these things is achieved, the identification of alpha in a deal would happen faster, which in turn makes it possible for capital to move faster and consequently for private markets to expand.”

Rogo’s Founder, Stengel, agrees. “There’s more value locked up in sub-$50mn enterprise-value SMBs than people realize. And those businesses are probably systematically undervalued, and there’s a huge, huge portion of the US economy in this long tail of smaller businesses … I think there’s a lot of attractive private market assets, but there’s not enough brain power and horsepower toward actually looking into them.”

Now, the last mile of private markets is traversable. As the cost of admission to AI automation has dropped precipitously, the calculus around automation vs. manual labor has shifted. At the same time, firms are facing pressure to compete in increasingly crowded and competitive venture and private equity markets.

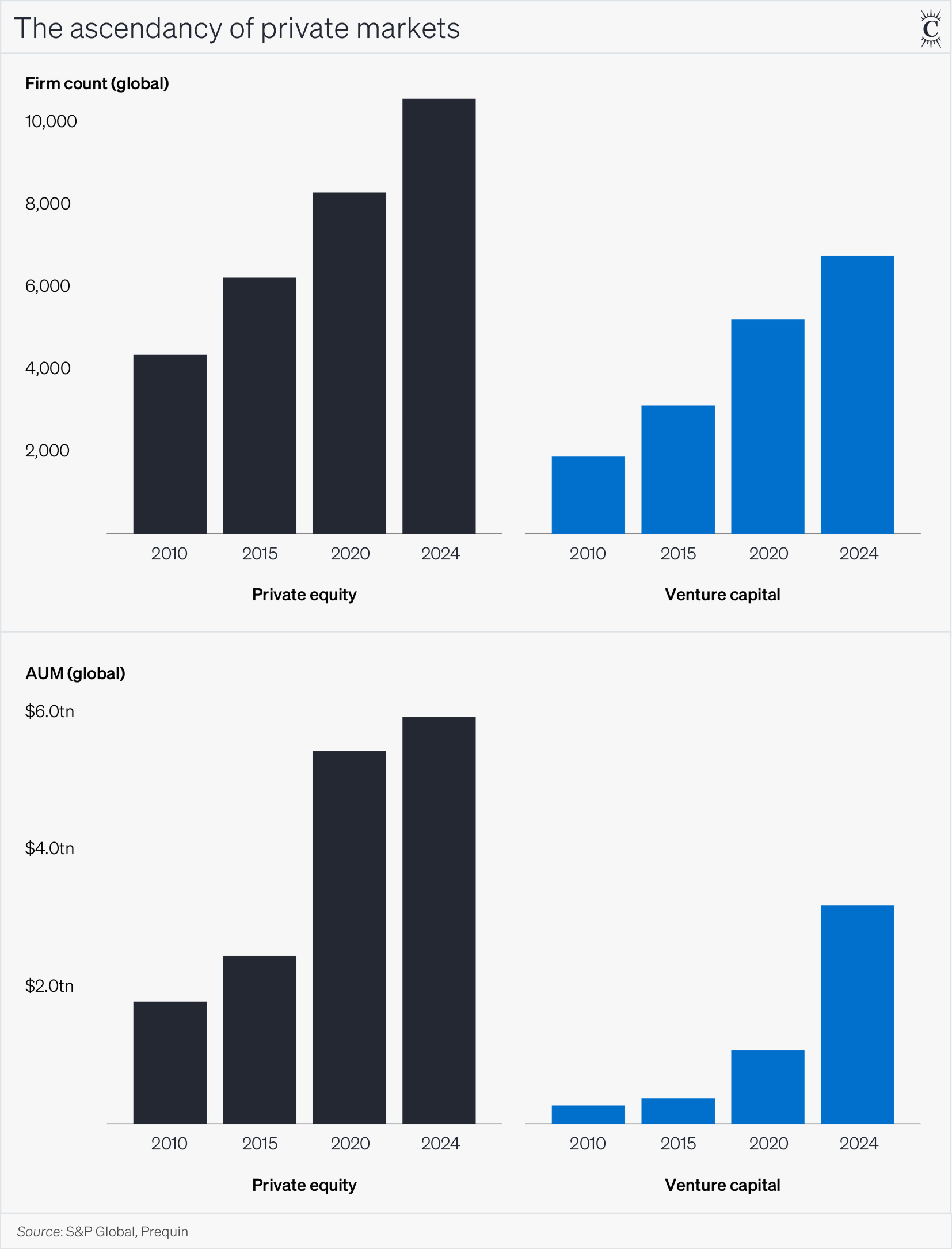

One of the most durable trends in private markets over the past decade has been growth in AUM. Assets managed by GPs are headed to $24 trillion by the end of the decade,[4] up from $19 trillion today and under $10 trillion in 2018.[5] There were 3x more PE and VC firms in 2022 than in 2010.[6]

The primary reason, of course, is return potential. Over the past 30 years, US buyout funds have consistently returned low double-digit percentages annually. The top quartile of funds have returned closer to 20%.[7] Venture capital returns were even more impressive, breaking 30% annual return on a 25-year basis in 2021.[8] Over the same time horizon, the S&P 500 averaged around 9%.

Jack Lynch is the VP Strategy at Ridgeline, a cloud-native asset management platform designed for the AI era. He covers financial markets, software, and AI on his Substack, Reading Ambitiously. We sat down with him to get his thoughts on where the market is headed. “In the 1990s, it was index funds and ETFs that rewrote the rules. Active gave way to passive,” Jack told us. “This time, the lines aren’t between active and passive. They’re between public and private. Between liquid and illiquid. Between price discovery and opacity.” Now, “active management hasn’t disappeared—it’s just moved upstream. It’s private equity, private credit, structured solutions. These managers are underwriting complexity, building companies, and shaping outcomes in ways public markets no longer reward.”

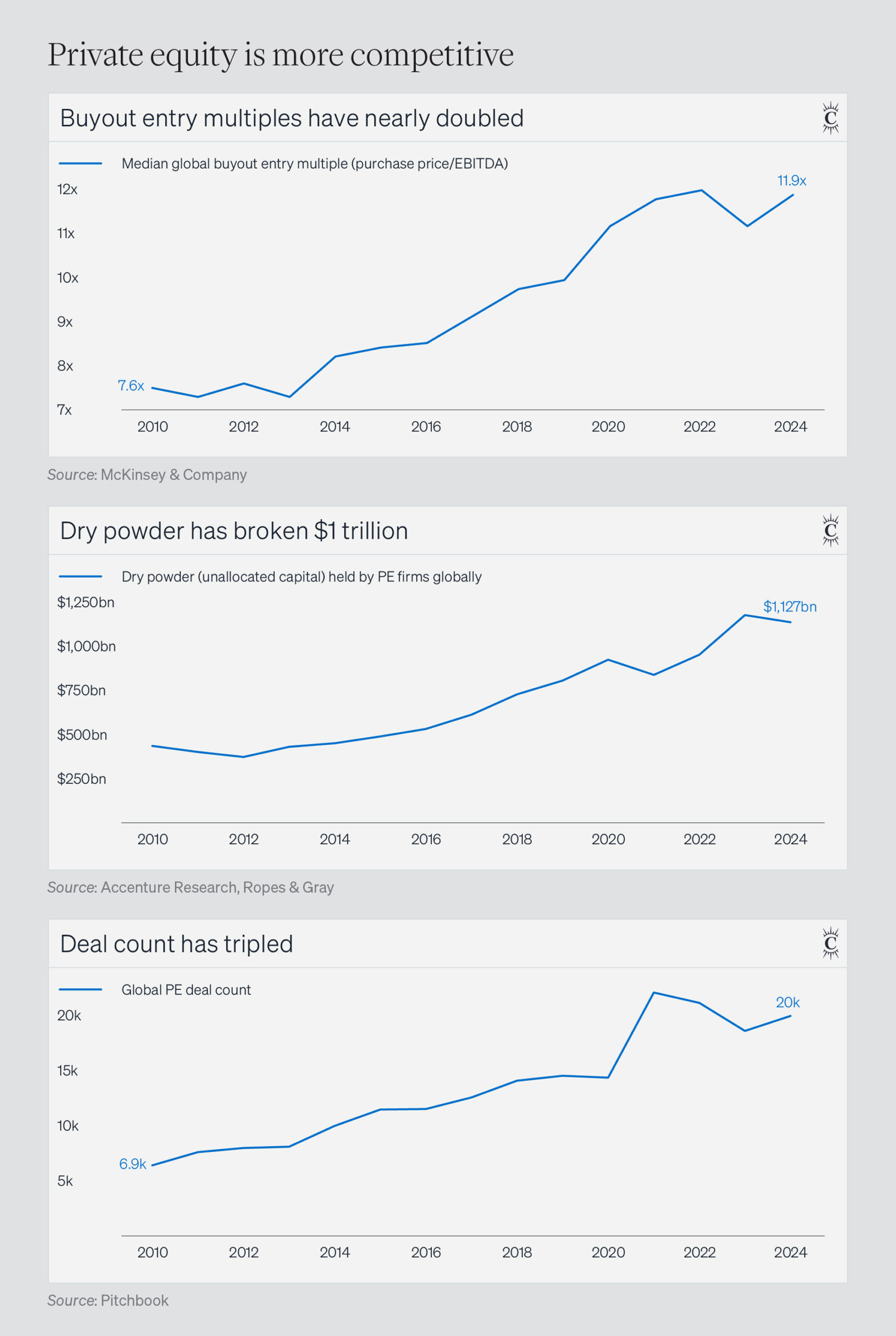

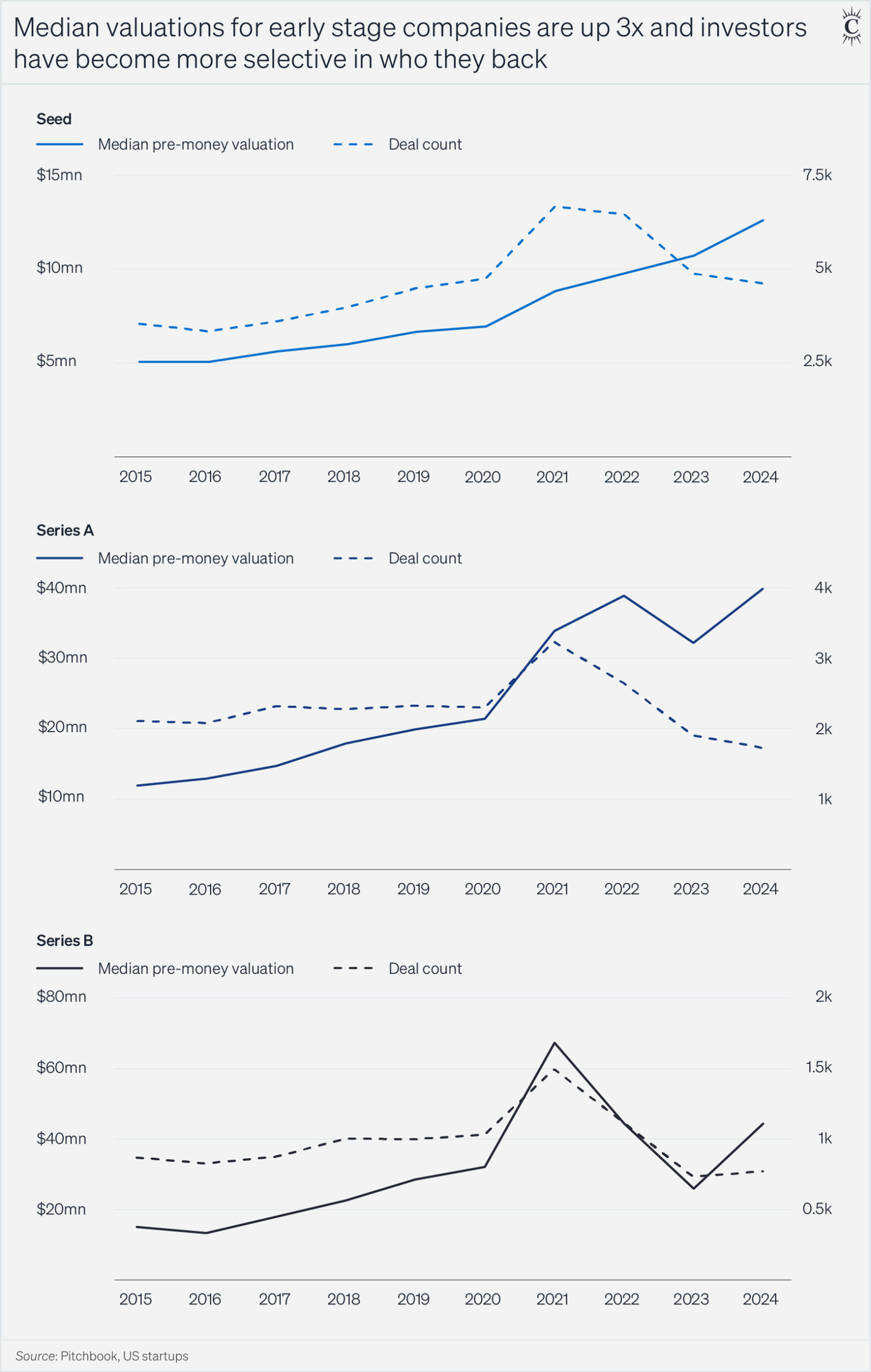

It has become abundantly clear that competition for the best deals is increasing up and down the deal stack. Private markets AUM has grown faster than the number of available, high-quality deals. In venture, median seed valuations have increased by 60% since 2020.[9] Over the past 15 years, global buyout EBITDA entry multiples have gone from 7.6x to 11.9x and all but the top quartile of buyout funds have seen annualized IRR decline by around 15%.[10] [7] A PE shift to mid-market may offer a temporary reprieve, but an investor at a mid-market buyout firm explained that “even at this level, we’re seeing some increased competition or increased market efficiency, and now founders are thinking, or have heard, that they should call a banker. I think we’re probably only five years away from the lower middle market getting way more competitive and banked.”

It is now becoming increasingly difficult for firms to find and win the best deals. Dry powder as a fraction of AUM in both venture and PE has steadily increased.[11] As the margin for error in delivering benchmark-beating returns has narrowed, firms are spending more resources on diligence. The number of days the average deal has spent in due diligence has increased by 30% over the past five years.[12] At the same time, the pressure to reach conviction quickly is ratcheting up thanks to competing capital aggressively hunting for deals.

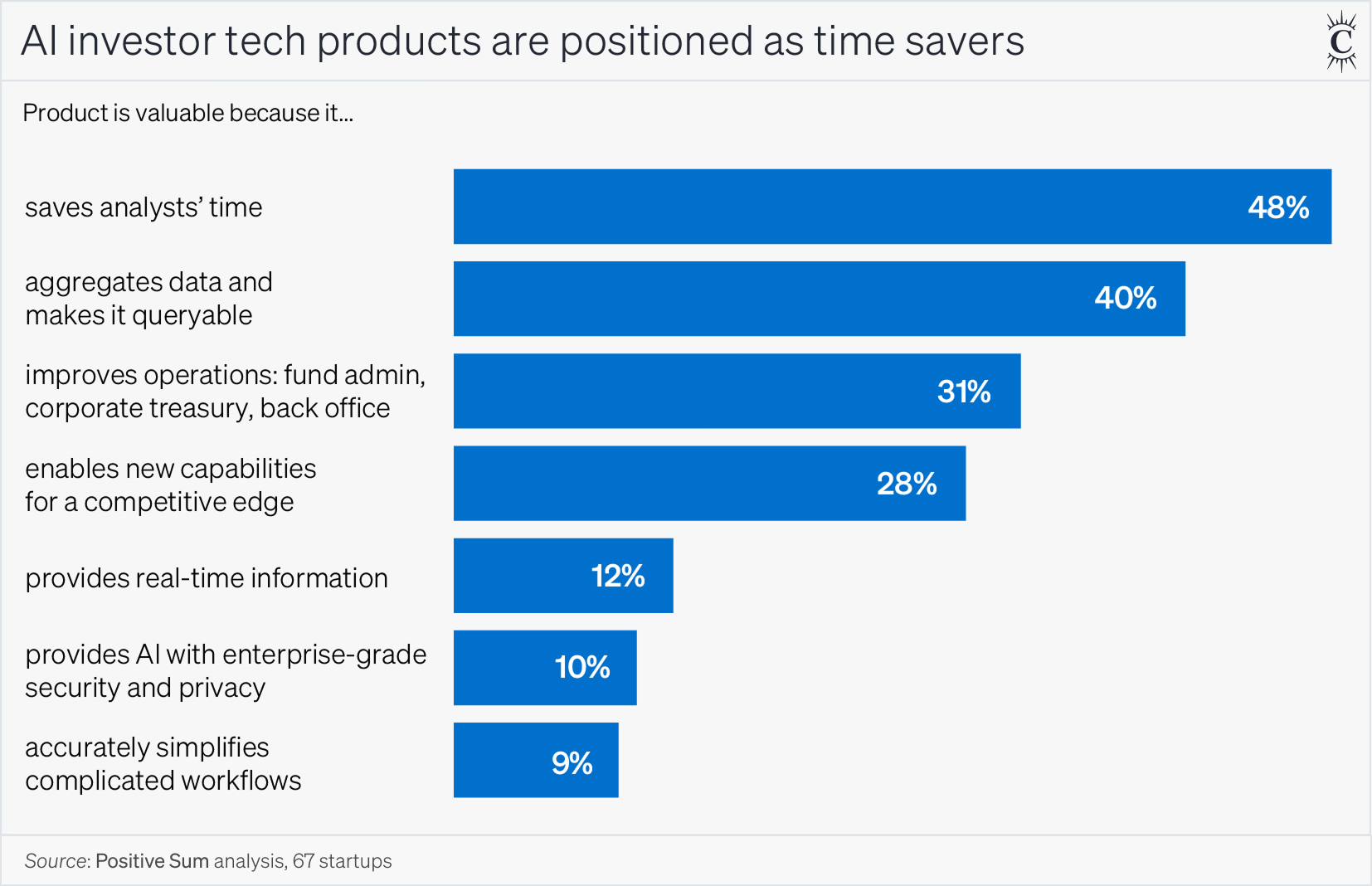

Today’s Alpha, Tomorrow’s Infra

Increased competition is pressuring firms to improve the speed, breadth, and efficiency of diligence and operations, and AI presents a compelling solution. Every firm can benefit from automating the undifferentiated heavy lifting currently delegated to humans.[13] “For 30 years, enterprise software has chased one promise: work should move itself… AI agents stand to finally finish the job,” writes Lynch. Consequently, nearly 70% of startups building private markets AI tools highlight time savings on their homepages—in the form of fast data aggregation, analyst efficiency, or real-time data feeds.

For 30 years, enterprise software has chased one promise: work should move itself… AI agents stand to finally finish the job.

—Jack Lynch, Ridgeline

The earliest AI adopters will gain an edge over their peers as they realize the benefits AI offers, like faster pricing backed by a broader set of data.[14] For the next few years, investment firms with the most aggressive and innovative AI strategies have an opportunity to defend their returns even as private markets AUM continues to grow. Consultants tend to focus on enumerating these near-term advantages of AI adoption.[15] [16] [17]

But as more firms incorporate AI into their workflows, edge will get diluted. First-mover advantages will be ephemeral. Scraping Form Ds as they are posted to identify companies raising new funding can give a sourcing edge, but only until other firms adopt the same approach. Flagging documents in a virtual data room that require immediate attention can help a team reach conviction faster than others, but only if the other data room viewers aren’t doing the same thing. In the long run, this will accelerate competition for many corners of PE and venture. Process automation is not process power.

Unless firms adapt to this world, it will once again become harder for them to reliably capture alpha associated with the best deals. This will be particularly true in growth venture and large-cap PE, where there are fewer overall deals, more external signals of traction, and greater transparency into a company’s operations. However, even the earliest stages of investing won’t be immune from this shift—venture investors are already pushing the price of the hottest seed-stage deals up, and new tools like Harmonic or Otto promise to make it easier than ever to identify those deals earlier.

It’s even plausible to imagine that as AI becomes ubiquitous, some pricing inefficiencies may go away. Rogo’s Stengel pointed especially at smaller deals, where heavy diligence processes don’t make economic sense. “I do think AI will result in being able to price risk more appropriately. The more transactions there are, the more data you have, the savvier folks can be. This will only increase across all of these different asset classes as AI is able to help you create downstream data research and synthetic data over almost every type of business and asset.”

Of course, the system is dynamic—firms are unlikely to sit on their hands and watch yields go down. Jack Lynch at Ridgeline emphasized that adaptation by the best firms will be how returns are preserved. “I do think that price discovery will be easier,” in a world where AI is at the core of every firm. However, he was skeptical that returns would be systematically pressured. The data supports this—while entry multiples for buyouts have crept up over the past 15 years, and returns have compressed since the early 2000s, the top quartile of firms have preserved their ability to deliver benchmark-beating returns. And, as competition in the large-cap buyout space has increased, firms have shifted focus to the less competitive mid-market—KKR raised $4.6bn for its inaugural mid-market fund in 2024.[18]

Regardless, the transformation of AI from alpha to infra in private markets is already underway. A third of asset managers have a full-scale generative AI use case deployed today. According to BCG, this could rise to as high as 95% within two years.[19] Sid Masson, Founder of Wokelo AI, an AI-powered due diligence platform, expects that the vast majority of venture firms will depend on AI in their investment operations within the next few years. Masson thinks the PE adoption curve may be slower, but it is just as inevitable.

Enduring Moats, New Strategies

So what happens next? Is the lasting impact of AI just task automation and more competition for the best deals? Perhaps even a slow asymptote toward public benchmark returns as yields are pressured? How will firms consistently generate alpha?

Through our conversations, we’ve come to believe that there will be two broad sources of investment edge:

- Traditional advantages. Successful firms will continue to rely on differentiated access, proprietary data, and operational leverage. AI will sharpen what these things mean, and investors today need to deliberately adjust their strategies to build moats around them.

- Emergent strategies. The widespread adoption of increasingly sophisticated AI across all parts of a firm will create a novel set of ingredients. This generates the opportunity for creative investment strategies that are impossible today.

Traditional differentiators will intensify

1. Access and trust

In an era where AI is embedded in every PE and venture firm, we believe even more dealmaking power will accrue to the investors that can develop a unique, repeatable motion to gain access to the best deals. This access can be built on top of firm reputation and brand, personal relationships, or operational value-adds. Ultimately, these things all tie back to trust—trust that an investor will be a great partner during inevitable difficulties, trust that a particular firm’s backing will accelerate value creation, or trust that a firm will be a responsible steward of a business. This trust is not fungible, and can’t be replaced by AI.[20]

AI will threaten the impersonal parts of sourcing. We spoke to one venture firm with several billion in AUM that’s built a data-driven sourcing platform to pull signals of startup traction from a broad swath of the internet, like social media, hiring patterns, and news articles. It then uses these signals to funnel ‘hot’ startups to a team of junior analysts who are tasked with establishing contact. This isn’t the only way the firm meets and invests in founders, but it provides each member of the sourcing team dozens, or even hundreds, of additional investment leads each week.

Generative AI makes this kind of tooling significantly easier to build. During our research, we met multiple firms that have used generative AI to vibe code their way to various analogs. Examples we’ve seen include:

- A multistage firm automatically grabbing new Form Ds and flagging companies as actively raising.

- An early-stage firm parsing inbound emails and enriching them with external data to build prioritized lists of potential investment leads.

- A seed stage firm that combines the backgrounds of founders with a high-level analysis of their ideas to identify promising pairings.

Startups are providing these capabilities as a service, too. Otto, a personalized outreach platform that uses publicly available telemetry to automate lead identification and initial outbound counts over 100 PE funds as users.

Hamill told us how this exact transformation played out in his career—after Bloomberg democratized market information, trust mattered more. In a world where other advantages were vanishing, cultivating personal relationships was an enduring way to maintain access to clients. After Bloomberg, he explained that entertainment budgets “actually went up, because dealers realized [that] now I need that customer to want to call me, instead of the other way around. All of a sudden, I need them to call me. Technology definitely drove that … As we got into a Bloomberg-driven world where everybody had all the information, then you were trying to get an edge by spending money to get the client to like you, to trust you.”

Just a block from South Park’s cluster of top VC firms, San Francisco’s iconic Caffe Centro (reopened in 2024) was where countless founder–investor relationships were forged over lattes.

As more and more firms adopt these low-cost tools, the ability of these tools to reliably deliver opportunities will get increasingly diluted. At some threshold, their primary contribution will be noise. A founder who receives one or two cold inbounds personalized with AI may reply; a founder who receives hundreds of such messages predicated on the same leading indicators will almost certainly not. This pattern has already played out in enterprise sales and hiring. As cold sales outreach at scale has become progressively easier and more personalized thanks to tools like Outreach or Salesloft, hit rates have fallen.[21] LinkedIn made it dramatically easier for applicants to apply for roles, and a founder in the recruiting technology space we recently spoke with described a sharp decrease in callback rates as a result—and a tendency for recruiters to prioritize employee referrals.

We think that adoption of automated, infinitely personalized sourcing tools in PE and VC over the next few years will lead to the same pattern. In turn, the ability of a firm or investor to create access that can’t be automated will become critical. Through this lens, firms that have already built this through a strong product or brand stand to increase their dominance. Y Combinator is the premier destination for early-stage SaaS founders. Sequoia or a16z on the cap table is a clear, positive signal for other investors. Thoma Bravo’s expertise in software has been cited in pre-emptive take-privates.[22]

Firms without this, who try and make up the difference with volume, will likely find themselves shut out of the best opportunities.

2. Proprietary data

On the data side, the key will be to create truly proprietary data—and make it legible to AI. As with unique access, the power of differentiated data about markets, companies, or people should come as no surprise to any private (or public, for that matter) markets investor. The difference now is in what qualifies as proprietary.

In the past, it has generally been forgivable to conflate ‘difficult to analyze’ with proprietary. Deal and valuation history, other investors, and headcount timelines are relatively easy to analyze thanks to tools like Pitchbook or FactSet. Social media mentions, policy documents, or online reviews require significant technical work to even get the data into a form that can be analyzed. Historically, analyzing this data was well beyond the scope of a small PE or VC firm’s capabilities. These barriers to entry can make an external dataset that adds marginal decision-making power something that only a handful of firms can contemplate using.

AI changes this. As it becomes far more efficient and cheaper to aggregate and extract signals from data, it becomes much easier for firms to do so. As they do, the value of these signals to generate returns gets diluted. This shift is already underway. The major LLMs, tools like Hebbia, and databases like Harmonic, already enable most firms to access and utilize more data about markets or industries than they could have before. For example, one early-stage VC firm we spoke with uses AI to build a ‘primer’ on every company it meets. This primer aggregates funding data, creates descriptions of key market dynamics, and explains any comparable attempts by other startups.

This pattern is reminiscent of the shift that bond traders went through during the late 1980s and early 1990s. At the time, the bond markets were paper-driven and opaque, which benefited firms that had the resources and networks to trawl the market for information. “There was a real asymmetry of information because the bigger the firm, the more information it had—just because of the network effect of people speaking to people,” Hamill explained. “The biggest dealers, Salomon Brothers, Goldman, etc. had that advantage and they used it ruthlessly. Drexel Burnham really had the advantage in the beginning because they sort of created a whole new market for junk bonds and made crazy amounts of money.” Now, “the bond market has become much more efficient. It’s as efficient as the stock market, I would say.”

What’s become clear in the market is that buyers want one tool that connects to their internal data and their external data.

—Gabe Stengel, Rogo

The easiest source of proprietary data is internal—deal and decision history, portfolio company reporting, and investment solicitations. These artifacts provide differentiated data points, but also encode a firm’s style and taste, allowing for even more tailored AI behavior. Unfortunately, it’s often very difficult to make these things visible to AI.[23] This is a primary focus for companies like Rogo: “What’s become clear in the market is that buyers want one tool that connects to their internal data and their external data. And so, the incumbents like Alphasense are creating platforms to do this,” Stengel said. “Ultimately you need both internal and external data together, right? You don’t want to hire a researcher who only can access internal materials, and then one researcher who only accesses external materials.”

3. Operating leverage

Another option is to double down on downstream, operational value creation levers, where AI is a valuable tool, but not a replacement for existing processes. This is less applicable for venture investors. However, operating alpha is a clear differentiator in private equity—a set of firms surveyed recently by Accenture aim nearly 80% of their value creation plans at operational improvements.[11] This number has steadily increased in recent years as a natural consequence of the competitive pressures we identified in previous sections. As deals have become more competitive and entry multiples have increased, firms have responded with greater deal complexity and longer holding periods to create space for greater operational intervention.

Of course, AI will play a key role here as well. Most obviously, in a direct way: the same benefits that AI delivers to dealmakers apply to portfolio companies as well. Last year, a Bain survey found that the majority of portfolio companies held by PE firms managing a combined $3tn+ were actively pursuing use cases for generative AI. Almost a fifth had already deployed applications to production.[24] The ways AI is being used are typically mundane, but can deliver significant operational efficiencies. One PE consultant we spoke with described an AI project to automate invoice ingestion into an ERP—hardly the use case AI technologists dream of, but one that allowed the company to replace a full-time role.

We see the next frontier as one of strengthening operating plans before a bid is submitted. Given the increasing importance of holding period activities, it should come as no surprise that value-creation plans are being mentioned in PE firm earnings calls nearly 4x more in recent years.[11] Like venture, AI is already being used during PE diligence and research to aggregate information and source deals. However, AI also makes it possible to continually update value-creation plans throughout the lifecycle of the investment, allowing firms to manage their holdings more effectively.

Assuming a firm has invested in a strong AI foundation, suddenly a static company analysis as it relates to deal evaluation, value-creation, and ongoing fund life management can be adjusted dynamically as one sees fit.

—Lydia Ofori, Plainr

Ofori, Plainr’s Founder, believes that AI will play a major role here, allowing PE firms to better forecast the range of possible outcomes during pre-deal diligence. “During deal management throughout the fund life, the opportunities for expansion as far as value creation goes [are] enormous. [With AI], you can see the possibilities for a company as clear as day,” she says. Furthermore, these plans can be updated with new information—both internal and external—much more frequently than before, enabling greater management precision throughout a holding period. “Assuming a firm has invested in a strong AI foundation, suddenly a static company analysis as it relates to deal evaluation, value-creation, and ongoing fund life management can be adjusted dynamically as one sees fit, to assess numerous end states and numerous opportunities. All in real time.”

Curious and contrarian

The areas we highlighted above—differentiated access, proprietary data, operating leverage—should feel familiar to most investors. However, there’s a deeper story at play, as the widespread adoption of AI creates a set of ingredients that have never before existed in private markets. The history of back-office automation illustrates the potential for unexpected change. “If you study what happened to bulge bracket banks when the back office got automated, the first-order effects were obvious,” said Stengel. Headcount migrated from rote, clerical work like manual trade-ticket matching and paper-based reconciliation, to higher value (and margin) activities.

Eventually, the cheap financial data feeds and computation resulting from this automation became low-cost services. In turn, it became feasible to build products that could serve small-balance customers at near-zero marginal cost, leading to a wave of direct-to-consumer financial services companies: neobanks, zero-commission brokers, robo-advisors, and more. “No one expected Chime, or some of these tools that went direct to the consumer. And really no one anticipated Robinhood.” With AI, “we’re still in the first-order effects range. The second-order effects are up for grabs, and that’s what I think is the most exciting opportunity.”

So, what might the future private markets landscape need to make room for?

New strategies will emerge

1. Continuous market measurement

One of the prime challenges in private equity and venture is the multi-year lag between underwriting an investment and realizing an outcome. In the February edition of the Consilient Observer, Michael Mauboussin, the well-known expert in predictive analysis in finance, writes, “Feedback in investing and business is impeded by noise and lag time between forecast and outcome.” The solution is logical—to “break down a thesis into subcomponents that are relevant over shorter time horizons.”[25]

This is a tall task when testing these subcomponents for more than one or two theses requires manually parsing reams of documents or continually monitoring newsfeeds. With AI, it becomes feasible to automate much of this work. Instead of infrequent, shallow updates – think quarterly emails to a founder to catch up over coffee, or tracking a few high-level quarterly earnings metrics across a manually curated compset—firms could automatically ingest a much wider array of data as soon as it becomes available. These could then be evaluated by AI models against a set of criteria (possibly AI-generated) relevant to the overarching thesis, with changes surfaced to humans.

For example, as the global pandemic unfolded, the lack of historical precedent, coupled with near-overnight changes to daily life, created space for a large number of equally uncertain investment theses. How long would lockdowns last? Would sidewalk robots replace food delivery couriers?[26] While it would have been impossible to quantify absolute likelihoods, tracking relative changes in likelihood would have been useful information. If US schools largely return to in-person instruction, as they did in late 2021, does it become marginally more or less likely that professional events remain virtual? More bluntly, should I invest in Hopin at $8bn in 2021?

Naturally, adopting this proactive approach brings advantages—investors are less likely to fall victim to sampling effects, where a point-in-time snapshot of a market may miss or underplay an important trend. They are also better positioned to capitalize on events than investors starting from scratch. In the 1980s, the venture firm Accel famously popularized the ‘prepared mind’ approach to venture, whereby investors arm themselves with an informed viewpoint on a company, business model, and market. The reasonable assumption underpinning this is that a prepared mind increases the quality of investment decisions. Assisted by AI, doing this continuously becomes feasible.

2. The quant-native private market investor

If a much greater volume of external data can be brought to bear in pricing thanks to AI’s ability to traverse the unstructured world, reliably triangulating valuation based on external factors alone starts to look tractable. Comparables already factor heavily into price-setting in both venture and PE. Markups between venture funding rounds tend to be similar company-to-company. PE firms already track public data across many potential investments on an ongoing basis.

Augmented with other public telemetry about management team, traction signals, or recent news, it’s not farfetched to believe that most companies can be priced reasonably well, even before data room access. Armed with this continually updating pricing data, investors could look for companies that are inefficiently valued against some overarching thesis, a purely capitalist strategy. Alternatively, investors could focus on frontrunning processes, pre-empting rounds by issuing term sheets or unsolicited bids far earlier than any competitors. In both cases, the ability to execute would depend on the ability to analyze more data, faster—the exact conditions AI creates.

Greater private markets liquidity would unlock these more quantitative strategies further. Right now, especially in venture, the decision to invest is tightly coupled with a prediction of ultimate company success. The intermediate off-ramps provided by a more liquid market would allow for strategies that hinge on accurately predicting shorter-term market movements. For example, a successful venture fund typically contains one or more power law returners—the Ubers and Facebooks of the world. These funds also contain a long tail of companies that are nevertheless viable (smaller) businesses. If these companies could be effectively priced and subsequently traded by more firms, PE-style distressed strategies or something akin to event-driven investing could emerge.

As another example, during our conversation with Stengel, he theorized that firms could potentially issue term sheets right away, as part of a spread strategy. “Instead of just writing a cold outbound email, I could send a cold inbound current term sheet. And I’d just say that we’re ready to price, and we’ll give you the liquidity instantaneously without having to spend a lot of time” he said. “I could envision a quantitative VC firm that front runs every process by offering term sheets with some pricing, and then immediately sells the assets in secondary to other firms. And then this firm could take a spread rather than the traditional VC process, which is buy and hold for 10 years.”

To be clear, there are prerequisites to most of these things happening. Right now, it’s difficult to actually convert any short-term pricing edge into an actual trade—deals take weeks to months to close, secondary sales take weeks to months to execute. And, companies themselves may continue to serve as a check even if greater liquidity materializes. Founders and management teams care who is on their board or helping them navigate go-to-market. “The best counterpoint to this thought exercise is that I care about who my investors are,” Stengel said. “There are probably founders and executives who don’t, but that’s going to be a forcing function to prevent some of this stuff we’re brainstorming.”

Nevertheless, speed to price and ability to bring better data to bear have always been sources of edge in investing, and we believe that to be true here as well.

3. Increased liquidity

So far, the unlocking of liquidity in private markets has been challenging to bring about, despite efforts from 2010s-era marketplaces like Forge, EquityZen, and Nasdaq Private Markets.[27] In 2024, total US secondary trading volume was less than 0.5% of public trading volume. Forge, one of the largest pre-IPO exchanges accessible to the general pool of accredited investors, accounted for only one-tenth of this small corner of the overall market.

Still, longer holding periods and greater private markets activity have created sustained interest in making exchanges for private assets accessible. Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock, devoted his 2025 Chairman’s Letter to making a case for private markets, and laying out BlackRock’s strategy to become a major private markets player. He wrote, “BlackRock has always had a foot in private markets. But we’ve been—first and foremost—a traditional asset manager. That’s who we were at the start of 2024. But it’s not who we are anymore.”[28]

AI won’t singlehandedly overcome the impediments to realizing greater private markets access. Today’s private exchanges mostly suffer from a deficit of infrastructure and lack of access: trades are often broker-mediated, even when wrapped in a UI layer, and can take months to clear. Only accredited investors can participate. Selling shares in a private company generally requires explicit approval from the company’s board of directors. Supply is limited for the top ‘pre-IPO’ companies like SpaceX, and demand is limited for shares in companies outside the top few dozen or so.

However, AI will act as an important tailwind to greater private markets liquidity, primarily by increasing the ability for investors to conduct price discovery. “For decades, private markets have been among the most opaque corners of finance. Investors know these assets hold long-term value—but exactly how much value? That’s not always easy to determine,” wrote Fink.[28] Currently, bid-ask spreads for secondaries can be enormous—up to 50%, a clear indicator of market opacity. As we noted previously, we believe AI will both make price discovery easier, and potentially more precise. This would act to increase market transparency, which in turn, could drive greater demand for private market assets, boosting efforts to increase liquidity.

Future private markets: AI-driven, competitive, and complex

Putting these pieces together, we see a future in which venture and PE become more complex, more quantitative, and more competitive. AUM will continue to increase across asset classes, meaning more capital chasing deals. As a result, investors will need to increase their ability to source the best deals earlier in a crowded market. They will also need to increase underwriting sophistication and speed in order to avoid mispricing deals, or missing them as others get through price discovery faster. AI will act as both catalyst and enabler.

Increasing competition will push some investors to go earlier and smaller. Smaller funds or solo GPs investing primarily on the basis of their differentiated personal networks and relationships may migrate here as institutionalization pushes earlier and earlier. On the PE side, a similar trend is likely to unfold, with larger firms taking advantage of the increased underwriting efficiency offered by AI to push even earlier in an effort to preserve returns. We’ve already heard from smaller mid-market PE investors that the ~$100mn deal space is getting more competitive.

As investors indexing primarily on access and taste move earlier and smaller, later stages will demand increasing rigor. In these segments, quantitative approaches will gain traction, with AI providing the technology on which these approaches are built. Assets will trade hands more frequently as it becomes easier to price, and spread strategies and shorter holding periods could emerge. Investing in these areas will trend more toward science than art.

Separate Truth from Beauty

The emergent strategies we explored are hypothetical, for now. No one is certain which AI applications and investment approaches will thrive in private markets as a consequence of today’s push for AI-driven operational efficiency. This has caused some investors to adopt a conservative stance toward using the technology. As one investor at a top 10 quant firm put it: “Right now, most investors are focused on cosmetic uses for AI, or applications that create operational efficiency, or just plain scared by the pace of progress from making investments in it.”

We believe the worst approach for investors is to wait and see which unexpected use cases or strategies take off. Models and products are changing rapidly, and sitting on the sidelines risks creating an institutional knowledge deficit that makes it difficult to recognize true step function improvements in the future. It also guarantees that any new ways of capturing alpha will go to someone else.

Instead, we think that investors today should be aggressively experimenting with new tools to understand what’s possible now, and adopting or investing in the most promising outputs.

For firms

For those looking internally at their own firm’s operations and strategy, the message is clear: adaptation is not optional. We believe it’s critical for investors to adopt a flexible, experimental mindset toward AI. The Bloomberg terminal showed how new investment technologies often have unexpected secondary effects, and these effects are often more impactful than the initial expected benefits delivered by a product built using the technology.

We’re still too early in the AI adoption curve to know what these things are. Stengel’s advice is to “allow yourself to experiment constantly in the near term on different tools, different types of workloads, different ways of thinking about investing. Don’t be afraid to dump tools. Don’t be afraid to force junior people on your team to mix up their process. Make sure that your vendor onboarding is easy, such that you can try five tools and constantly experiment. The firms that are the best are going to be the ones that are constantly experimenting and then doing what sticks.”

The firms that are the best are going to be the ones that are constantly experimenting and then doing what sticks.

—Gabe Stengel, Rogo

Even the most adventurous firms can’t test every new tool, so investors must be able to identify the most promising ones. Maithra Raghu, the Co-founder of Samaya AI, a company building expert AI agents for financial services, was quick to point out that this requires more than simply demoing new products. “It’s important to separate ‘Truth’ from ‘Beauty’ in AI,” she told us between fielding investor calls at Samaya’s Mountain View office. “Beauty is the exciting new AI demo—the ‘expert-level’ Deep Research that wows at first look, works in carefully constructed examples, but falls short in the real world.”

Raghu gave us a framework for cutting through the hype. First, look for teams building products explicitly for financial services; general-purpose tools often struggle to get the details of specialized finance workflows right. Second, look for teams innovating at both the model and product layers, with tight feedback loops between them. Finally, ask for proof: teams should be able to show that their products consistently outperform off-the-shelf models in head-to-head benchmarks. These products stand the best chance of long-term relevance. “Truth is the enduring impact AI has on the real world,” Raghu said. “It’s the AI that is painstakingly constructed to handle the ambiguity, noise, and complexity of the global financial ecosystem. It takes a lot longer to build this truth, but its effects are lasting.”

While aggressively experimenting, firms can (and should) invest in backend work that puts them in the best position to get the most out of any AI tool they try. “Figure out what [are] the foundational bets you need to make, and start investing in them right now, to set yourself up for success no matter what. Those are things like putting in a real data layer, such that you are tracking what everyone does and centralizing it and making it queryable,” Stengel said. “Make the longer-term infrastructure bet to organize your data in a way that is AI-friendly, such that even if you’re not using ChatGPT or Rogo or another AI product right now, it’ll be easy to turn the faucet on when you need it.”

For investors

Investors looking at opportunities in investor tech should be excited that today’s alpha is tomorrow’s infra. Infra is investable. The infrastructure that private markets depend on will soon have AI at its core. Startups building in this area are chasing a $100bn+ revenue opportunity currently occupied by human labor. While a stack has already emerged, with companies like Hebbia, Rogo, Harvey, Plainr, Samaya, and more scaling quickly, we believe that we’re still in early innings—most firms haven’t yet adopted AI comprehensively across their organizations.

We believe that AI-powered tooling for private markets represents an eminently investable, horizontal thesis, with significant value left to capture for startups building in this area. We’re particularly interested in products that tackle voice AI use cases, like expert network calls, those that help investors access and integrate capital flows data and other market telemetry into their day-to-day investment work, or enable firms to make more of their internal data legible to AI models.

Ultimately people—founders, builders, and investors—are what will drive AI’s impact on private markets. Technology alone won’t transform the trajectory of venture and PE over the next decade. Jack Lynch has perhaps the best advice to offer for anyone looking to successfully navigate the new opportunities created by AI. “The best investors are intellectually curious, they are contrarian, they are independent thinkers,” he explained. “Investing is of course a science, but equally an art. The science now promises to be enabled by new technology, but the art is what the world’s greatest investors have in common.”

Donald Lee-Brown is the director of research and Terran Mott is a research analyst at Positive Sum.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following individuals who also contributed ideas for this piece:

- Ryan Eisenman, Founder and CEO of Arch

- Tim Flannery, CEO and Co-founder of Passthrough

- Mason Lender, Co-founder of Vantager

- Sid Masson, Founder and CEO of Wokelo

- Dhruv Tandon, Co-founder of Decisional

Positive Sum is an investor in some of the companies discussed or referenced in this article.

Click here to subscribe to print for your office or home.

The scar catches the dying light first—a crescent beneath Ramtin Naimi’s left eye that vanishes when he smiles, which he does often these days. From the terrace of his Tiburon home, the 34-year-old venture capitalist commands a view that stretches across the entire Bay Area: San Francisco glittering in the center, the Golden Gate Bridge suspended to the right, Berkeley and Oakland pooling to the left. Container ships drift beneath the bridge like bath toys while planes climb from SFO and small yachts chase the last breeze.

“It might be the nicest view in the world,” Naimi tells me, sipping a glass of Napa red, which his wife Lizzy notes as a rare indulgence. He’s dressed in his standard uniform: black Saint Laurent cap, t-shirt, and jeans; minus the white Vans he kicked off after arriving home.

The Transamerica Pyramid rises from San Francisco’s skyline like a pin, marking the neighborhood where Naimi runs Abstract, his $1.8 billion venture firm. From this vantage point, success appears inevitable. But tonight, his gaze drifts past the pyramid toward Van Ness Avenue, where 11 years earlier a very different version of Naimi sat in a bankruptcy lawyer’s waiting room, surrounded by fluorescent lighting and the particular desperation that smells of instant coffee and broken dreams.

The journey between those two points—from insolvency to influence—reads like fiction, the kind of story editors reject as implausibly neat. Yet here sits the evidence: a man who parlayed supernatural hustle, pattern recognition, and an immigrant’s refusal to accept limitations into one of the Valley’s most successful seed firms, backed by Stanley Druckenmiller, Bill Ackman, Kevin Warsh, and Michael Ovitz.

“I’ve been discounted by so many people in my life,” Naimi says, and the scar under his eye seems to deepen in the fading light.

Money lessons in the Naimi household arrived with the subtlety of a Persian carpet seller. “America revolves around money and you need to figure out a way to make it,” his father repeated like a family motto.

His parents had been childhood neighbors in Tehran before the Iranian Revolution scattered them across continents. They found each other again in Los Angeles as young adults and married in 1984. By the time Naimi was born in November 1990, they were living the classic immigrant story: small business owners grinding their way toward the American Dream.

His father cycled between restaurants and dry cleaners, arriving home past midnight only to rise again at 6am, stress permanently etched into his face. CNBC played constantly in their household, his father monitoring markets that had nothing to do with his businesses.

When Naimi turned 12, his mother announced they were moving to San Francisco to be near her sister. Naimi, his older brother, and mother crashed with his aunt’s family for three months while his father liquidated everything in LA. The family then settled in Tiburon, first in a cramped one-bedroom apartment, then a two-bed, and finally a modest starter home.

His mother prioritized neighborhood over house size. “We were the tiniest fish in the biggest pond. I had friends whose fathers were the CEO of Visa or the CEO of Blue Shield and lived in these extravagant homes. I knew these things existed, and I knew the path to them wasn’t being a doctor or a lawyer,” Naimi explains.

In high school, Naimi discovered a gift for seeing systems. His first entrepreneurial venture emerged from observing an inefficiency in Marin County’s social hierarchy: the divide between girls whose parents threw elaborate Sweet Sixteen parties and those whose parents couldn’t. His solution was financing celebrations for anyone who wanted one.

Naimi would rent venues, hire DJs, arrange insurance, and recruit security from local gyms: “roided-out meatheads” who worked for $50 a night. The birthday girl got her party with her name on the banner and DJ shout-outs. Naimi got to charge admission and invite kids from every high school in Marin County, whether they knew the birthday princess or not.

His first party nearly bankrupted him. He’d spent so much on production that his parents worried he’d lose his savings. But within 10 minutes of opening, his pencil box overflowed with cash. He had to run to the bathroom for a garbage bag.

To float his party empire, Naimi worked weekends at West Elm, the furniture store. He would spot customers who’d rented Zipcars—clearly intent on taking furniture home—and aggressively upsell them using the store’s progressive bonus structure. “Somebody would come in wanting to buy a sectional,” he recalls. “I’d ask, ‘Do you want the pillows? The coffee table? The rug?’ They’d say no, just the sectional. So I would take off all the accessories just to show them what it would look like at home.” He ended up with the highest average ticket sales at the store.

But Naimi’s real education was happening in front of a screen, where his father’s CNBC obsession had metastasized into something more dangerous. At 13, he convinced his parents to lend him $2,000 to learn stock trading. When $2,000 proved insufficient for meaningful equity positions, he migrated to derivatives that could multiply his buying power.

The timing was fortuitous in the way that only hindsight reveals. As the 2008 global financial crisis unfolded during his senior year of high school, Naimi was trading out-of-the-money options against triple-leveraged ETFs tracking the banking sector. These instruments swung 10–30% daily based on Federal Reserve announcements or news about Lehman Brothers’ impending collapse. In the weeks surrounding Lehman’s bankruptcy, he made several hundred thousand dollars.

The success proved intoxicating. Instead of college, Naimi launched a hedge fund straight out of high school. He obtained his Series 65 license and began raising capital from the network he’d built around a local financial advisor’s office in Tiburon. In total, he raised $3 million from 45 investors. He was the largest LP in his own fund, having poured his $500,000 of trading profits into it.

In January 2009, aged 19, he launched the fund at the nadir of the financial crisis. He now concedes the absurdity: a 19-year-old kid ripping options all day long, trading iron condors and selling naked puts on levered ETFs and volatile tech stocks.

The fund produced 59% annualized returns over three years—no small feat for a self-taught teenager. But the emotional cost was brutal. Naimi lived chained to his six trading screens, taking only two vacations in four years, both cut short by panic attacks when separated from his terminal. There were months when the fund dropped 27%; others when it rose 28%.

The transition away from his screens was catalyzed by growing curiosity about the technology industry buzzing around him in the Bay Area. He cold-emailed VCs, angel investors, and founders, trying to understand what was happening in Silicon Valley. Most ignored him, but a few took meetings, including Stuart Peterson, who ran ARTIS Capital.

“He showed me the scale of private companies, how many were staying private longer, and how much alpha was getting picked up in private markets,” Naimi remembers. More importantly, Peterson identified something about Naimi’s personality that he hadn’t recognized himself: “My personality is much more suited to being out hustling and meeting founders and learning about new technologies than sitting by myself for 15 hours a day.”

He wound down the fund in 2013 with $1.5 million in the bank and quickly stumbled into a significant problem: his lucrative detour had severed him from the credentialing system that governed Silicon Valley access. He had returns but no relationships; quantitative skills but no understanding of how venture capital actually worked.

Davidov and Naimi in the entranceway to Abstract’s Jackson Street office.

The rejections came wrapped in encouragement and condescension. “Hey, listen, your background’s not that relevant to venture capital,” became a familiar refrain. “Maybe you should start a company.”

Naimi spent months trying to penetrate an ecosystem that prided itself on meritocracy. “Rinky-dink hedge fund manager,” as one person characterized him, didn’t fit the template of Stanford computer science degrees, Harvard MBAs, successful startup exits, or family money.

If starting a company was the price of admission, he’d pay it. In 2014, during the marketplace lending boom, he identified what seemed like an obvious market inefficiency. Companies like Lending Club and Prosper were growing rapidly, issuing loans with three- to seven-year maturity periods. But unlike banks, which traded debt instruments as liquid assets, peer-to-peer lending offered no secondary market.

Naimi built Lenders Exchange to allow debt investors to trade their positions before maturity. He self-funded the company, assembled a team, and worked through the complex regulatory framework required to operate a trading platform.

Fourteen months later, when he finally had a product ready for external financing, the sector collapsed. Lending Club’s stock plummeted 85% from its IPO peak. Sequoia began writing down its Prosper investment to zero. The category became untouchable.

“I had spent my entire net worth building a supplemental product to a collapsed industry,” Naimi says. The failure wiped him out completely, but worse was the debt he’d accumulated keeping the business alive. Credit cards ballooned to $300,000 as he tried to bridge toward a fundraising round that never came.

The emotional devastation matched the financial ruin. His parents, who had watched their youngest son make millions, now watched him sink into insolvency. The Persian immigrant values that had driven his early success cut him deeply. Money mattered in their household, and he had lost all of his. His mother never criticized him directly, but her heartbreak was visible. His father was “livid,” but later acknowledged Naimi’s resilience: “99 out of 100 people just would have gone into a hole for the next six months,” he reassured him. “You were grinding the next day.”

The bankruptcy lawyer’s office on Van Ness Avenue represented everything Naimi had spent his life trying to avoid: fluorescent lighting, plastic chairs, worn carpet that reeked of stasis. Everyone looked resigned to circumstances beyond their control.

He was flat broke when he Googled “bankruptcy lawyer San Francisco” and clicked the first result. The rumpled lawyer matched his surroundings perfectly. Naimi explained his story. The lawyer listened, then smiled with unexpected warmth.

I had spent my entire net worth building a supplemental product to a collapsed industry.

–Ramtin Naimi

“I’m not the lawyer for you,” he said. “I do Chapter 7 bankruptcies. Chapter 7 is for people who are down on their luck and not getting back up.” He reached for his phone. “Let me call Brent. He’s the person you need to see. You need to file Chapter 13, not Chapter 7. You’re going to start making money again quickly. I know you will. You just need to restructure your debts.”

The lawyer surveyed his waiting room, then looked back at Naimi with something approaching respect: “You’re not like these guys.”

An hour later, he was in a much nicer law firm, explaining the same story to Brent, who wore a proper suit and worked from an office with actual artwork on the walls. Chapter 13 turned out to be straightforward. Within two years, Naimi had cleared every debt.

But sitting in that waiting room, surrounded by people whose circumstances felt permanent, Naimi faced the possibility that his confidence had been misplaced, that his early success had been luck rather than skill.

The unexpected faith from a grizzled lawyer righted him. The near two-year saga that had emptied his bank account had also carved something permanent into his character: a chip on his shoulder that would prove more valuable than any credential.

One of the VCs who had passed on his marketplace lending company was Arjan Schütte, Founder of Core Innovation Capital. Naimi was interviewing for account manager roles at any startup he could find (and getting rejected) when Schütte offered him a modest role at Core: part intern, part associate. Naimi grabbed it like the lifeline it was.

“He had a very strong style and a Rain Man-like memory for numbers,” Schütte recalls. “I remember being struck by an unusual outlier talent, and he just needed a home somewhere.” For Naimi, it is still the kindest thing anyone has ever done for him. The salary was minimal and he was mostly left to his own devices, but the credential was invaluable. After years of rejection, he finally had a venture capital business card.

Core was a fintech-focused firm doing Series A investments. It didn’t take long for Naimi to realize that wasn’t his calling. He wanted to be a generalist seed-stage investor, catching companies at their earliest and most malleable stage. But the traditional path—working at a venture firm for several years before being granted check-writing authority—didn’t suit his timeline or temperament.

As he absorbed what he could from Core, he began reverse-engineering his path to seed investing. He meticulously researched power law outcomes—companies worth more than $5 billion—and made a counterintuitive discovery: multi-stage venture firms were better at seed investing than dedicated seed funds.

“At the time, if you eliminated Uber and Roblox, whose seed rounds were led by First Round Capital, you couldn’t point to a single power law outcome within a venture timeline where the seed round was led by a seed-stage venture firm,” he explains.

The pattern suggested that seed funds claiming proprietary deal flow were, in Naimi’s characteristically blunt assessment, “full of shit.” How could a three-person seed fund have better coverage than a 50-person multi-stage firm?

Instead of competing with these giants, Naimi decided to align with them. He chose to become a seed investor that treated multi-stage firms as partners rather than competitors, accepting smaller ownership stakes in exchange for access to higher-quality deals. It was a radically different approach that required abandoning the traditional seed fund playbook.

But first, he needed deal flow. He analyzed the backgrounds of founders backed by top-tier VCs, identifying patterns in education, work experience, and career trajectories. He built a LinkedIn scraper to track roughly 7,000 people who fit the profile.

“Anytime one of them changed their job title to founder, I got a push notification,” he explains.

Nine times out of ten, the change happened before they raised funding. Naimi discovered that “an unfunded seed stage founder is the easiest person in the world to get a meeting with.” But meetings didn’t equal investments. He needed capital, and banks weren’t lining up to fund a recently bankrupt 25-year-old.

The breakthrough came via AngelList. Naval Ravikant’s platform allowed anyone to raise SPVs for individual deals—no permission required, just quality deal flow. When Naimi posted his first opportunity, Ripple, he raised $470,000 within four hours.

“I was like, holy shit, what was that? This is incredible. I can’t believe this actually works.” The economics made it even sweeter: He would earn 15% carry on every SPV he syndicated through the platform.

Naimi sobered up quickly when forwarded emails began arriving, accusing him of hijacking the deal. An experienced AngelList investor alleged that he had been raising his own Ripple allocation when Naimi’s SPV went live. They contacted Ripple’s CEO Brad Garlinghouse and Schütte at Core, claiming the young investor had misrepresented his allocation and had “no right” to syndicate the deal. Naimi’s stomach dropped. He worried about being fired from Core and offered to retract the SPV.

Salvation came from Garlinghouse himself. Ripple’s CEO validated Naimi’s allocation and praised his transparency, providing crucial backing when his credibility hung in the balance.

Naimi then went turbo.

Gil Penchina, a legendary angel investor, helped him navigate the platform’s mechanics and lent credibility to his efforts. “Gil had a big following on AngelList. He let me market my first few SPVs to his LP base as a way to get me on the platform,” Naimi recalls.

Lee Jacobs, who managed syndicate partnerships at AngelList, watched with amazement: “At first it was almost unbelievable. Every week, this random dude would send lists of 15 companies backed by tier-one firms. He wasn’t a founder, and hadn’t worked at a tech company; it came out of nowhere.” But the deal flow proved real, and Naimi quickly became one of the platform’s top investors.

For six months, Naimi represented roughly one third of AngelList’s total volume. Between August 2016 and June 2017, while technically employed by Core, he invested in 47 seed-stage companies either via an SPV raised on AngelList, or as an angel. Two of them—Solana and Ripple—went on to have coin market caps worth more than $100 billion each. A third, Rippling, is now valued around $17 billion. He also caught early rounds of future unicorns like Clay, Cherry, Material Security, and NewFront. His SPV investments have already returned just under $100 million to investors.

Word of Naimi spread quickly through Silicon Valley’s network. By early 2017, everyone wanted to hire him. By August, when he had momentum doing his own thing, he was declining those offers and fielding proposals from VCs wanting to become LPs in a fund he didn’t yet have. He wasn’t convinced the approach would scale to a full fund, but when the conversation evolved to buying equity in his management company, the equation became too attractive to ignore.

In the deal that emerged, Marc Andreessen, Chris Dixon, David Sacks, Keith Rabois, Michael Ovitz, Kevin Hartz, Bill Ackman, Stanley Druckenmiller, and Kevin Warsh bought 20% of his management company, Abstract, for $10 million in upfront cash. Naimi was 26 years old with a theoretically worthless company that had maybe $10 million in total assets under management.

“It was a group that I’d only read about and would have given the equity to for free if they’d asked for it,” Naimi says. “But if they were willing to pay for it, then that made it even better.” The deal included a seven-year sunset provision, whereby the investors earned economics on everything Abstract did in that window. By the end of 2024, Naimi owned 100% of his firm again.

This is the single most important person you’ll meet, whether you succeed or fail. Ramtin is the key to the kingdom you want.

–George Sivulka, Hebbia

The consortium came together through a web of introductions: Cyan Banister, whom Naimi knew from AngelList, introduced him to Hartz; Hartz made introductions to Rabois and Dixon; Dixon brought in his partner Andreessen; Andreessen suggested Naimi meet his mentor, Ovitz; Ovitz connected him to Ackman, Warsh, Druckenmiller, and Sacks.

Hartz, who founded Xoom and Eventbrite, remembers thinking: “If you were this good not knowing anybody, I wonder how much better you’ll get if you know all the right people.” Ackman, founder of hedge fund Pershing Square, was drawn to a familiar story. “I was once a 26-year-old trying to raise money,” he told me. “Ramtin seemed smart and had a lot of energy. He was very entrepreneurial. I liked his strategy and the way he was building his business.”

For his part, Ovitz said, “I got an instantaneous sense that this was a guy to develop and mentor. I went out on a limb with him, bringing quite a few large investors to the table, which I rarely do without really knowing somebody. But it turned out I was right.”

Naimi remembers his first meeting with Ovitz differently. He arrived at The Battery restaurant in San Francisco so nervous he could barely think straight, overwhelmed by the aura of the man who’d built CAA from nothing and negotiated deals for Sony, Steven Spielberg, and countless others.

The Hollywood legend settled into his chair, took a deep breath, and delivered a line that almost broke Naimi’s composure: “To what do I owe the pleasure?”

“What do I say to that?” Naimi thought, scrambling for an answer that wouldn’t sound ridiculous.

Midway through the conversation, they stumbled upon the topic of cars. Ovitz mentioned he’d dabbled in collecting vintage cars but that storage was a pain, so he’d never taken it seriously. He’d once been offered a collection of 12 classic Ferraris from an estate sale.

“Guess what I could have bought the collection for?” Ovitz asked.

Naimi clarified what year and which specific cars were included. Eleven were standard classic Ferraris. One was a 250 GTO—among the world’s most valuable.

Naimi calculated rapidly. “I don’t know, they probably wanted $18 million.”

“That is spot on!” Ovitz replied, extending his fist for a bump.

“From there, we were just kind of buddies,” Naimi recalls.

Eight years later, their relationship has deepened into something closer to family than business. Ovitz describes Naimi as his “non-biological son” and marvels at his intensity. “Everything he gets into,” Ovitz told me, “he approaches with the same vigor, but it’s not the kind of intensity that’s a turn-off. He’s grown into one of the best investors out there.”

Naimi counts Ovitz as one of his best friends. The pair, separated in age by 44 years, talk every day in conversations that range far beyond venture capital.

“We talk about art, for example,” Ovitz says. “He wanted to collect art, and I got him started. I’ve gotten a lot of guys started but most of them don’t follow through. Ramtin is building a very impressive collection. He has worked hard to learn. He listens well.”

Both Ovitz and Stuart Peterson—Naimi’s original mentor who introduced him to venture capital—possess world-class collections. “Every time I visit them, I just try to learn a little bit more about what’s in their house,” Naimi says. “They could both spend two, three hours walking you around their home and talking about what they have and how they got it and the story behind it, the history behind it, the significance of it.”

Naimi now owns works by Christopher Wool, George Condo, Mark Grotjahn, Larry Bell, and other masters. He approaches art collecting with the same systematic intensity he brings to venture investing: studying markets, building dealer relationships, and hunting for pieces before they become widely recognized. Abstract’s office is littered with striking art, although Naimi classifies them as “pieces that won’t make me mad when someone bumps into them.”

Naimi’s other best friend (the third being his wife, Lizzy) is Hartz, who works a block away on his own early stage venture firm, A*. In addition to being a close friend, he serves as a tactical sounding board and deal-making partner. Naimi calls him “Kevie” and talks to him four hours a week.

That Naimi has cultivated close relationships with people who could have easily dismissed him as just another ambitious upstart seeking their stamp of approval says as much about his personality as his capabilities as an investor.

The $10 million in upfront cash from selling equity in his management company solved Naimi’s immediate financial problems and gave him the resources and network to build Abstract into a real venture capital firm.

He made his first hire in 2017, recruiting Alex Davidov from Core Innovation Capital as a Founding General Partner. Where Naimi was the front-facing relationship builder and deal sourcer, Davidov would be the operational backbone that could systematize Abstract’s approach and scale its capabilities. “Alex and I are polar opposites,” Naimi explains. “I’m an eternal optimist and he’s kind of a default skeptic, which I think is a healthy balance to have.”

Both have trading backgrounds—Naimi from his hedge fund years, Davidov from four years at Bridgewater Associates—which give them a shared framework for thinking about venture capital as a methodical problem rather than a collection of isolated bets.

Their first fund targeted $100 million. Most advisors suggested starting smaller, but Naimi was determined to make a statement. “I wanted it to be significant enough that people had to pay attention to us,” he says. “It wasn’t just going to be another $20 million seed fund. It was going to be a $100 million seed fund.”

The same individual investors who’d bought equity in his management company became anchor LPs, providing roughly half the capital. The remainder came from another set of individuals: Joshua Kushner of Thrive, Matt Cohler of Benchmark, Neil Mehta of Greenoaks, Chase Coleman of Tiger Global, Santo Politi of Spark. Four institutional LPs participated. Naimi also attracted operators like Jerry Yang from Yahoo and Frederic Kerrest from Okta.

The final close came down to the calendar deadline. The terms they’d set with investors gave them exactly one year from first close to complete the fundraise. On Christmas Eve 2019, Naimi was visiting family when his phone rang. An Israeli family office wanted to commit the final $2 million. “We nailed $100 million on calendar day,” he says with satisfaction.

Abstract’s first fund systematized and scaled Naimi’s SPV approach: Identify companies before the multi-stage firms find them, then introduce those companies to the right partners at tier-one firms.

We are the best firm in the world at getting founders from seed to Series A.

–Ramtin Naimi

But the strategy required reimagining traditional venture capital portfolio construction. Abstract’s model focused on “relative ownership” rather than absolute ownership: If he could get 5% ownership in deals where Andreessen Horowitz got 15%, he might have one-third their ownership, but out of a fund that was one-fifteenth the size, his LPs got 5x more exposure to those companies than they would as investors in Andreessen’s fund.