Click here to subscribe to print for your office or home.

We’ve barely scratched the surface of the total opportunity in robotics. If today’s startups achieve their ambitions, they will unlock over $1tn in revenue and disrupt how virtually every industry operates.

Breakthroughs in robotics could massively expand existing verticals and unlock new ones. In established markets like manufacturing and logistics, there’s ample opportunity to increase robot adoption. In logistics, robots still leave 95% of the world’s warehouse space untouched—a $50bn revenue prize.

Then there’s the long-held science fiction promise of helpful robots in our homes and daily lives. Enticing demo videos show robots doing complex tasks in homes—handling cooking utensils or navigating a messy living room to deliver a drink. But even simple robots could unlock huge consumer markets. The two-decade history of robot vacuums shows that a premium point solution for consumers is still worth billions of dollars annually.

There’s immense value to unlock from getting more robots into the world. But the hard truth is that getting robots into the world is easier than keeping them there.

The challenge of commercializing robots means that companies have captured a vanishingly small fraction of the total opportunity on the table. Only two robot form factors have been broadly commercialized: industrial robot arms for manufacturing and robot vacuums. Other robot applications have struggled to gain traction. In the past decade, $26bn of venture funding has gone into US companies to bring robots to new markets. This investment has brought many robots out of the lab, but with little real progress past pilot testing.

Most robotics startups—and their investors—have focused on hardware. But through our deep-dive research and conversations with the best technologists and founders working on robotics today, we’ve concluded that the real bottleneck is software.

Robots are held back from wider commercialization by a lack of software that gives them the competence to reason about open-ended situations. For robots to reach their full potential in existing markets, and conquer new ones, they depend on software breakthroughs that make them more adaptable. With more adaptability, warehouse robots could take on broader tasks and better collaborate with people. Delivery robots could make smarter decisions about anomalous situations in hallways and on sidewalks. Consumer robots could expand their capabilities in messy, unpredictable home environments.

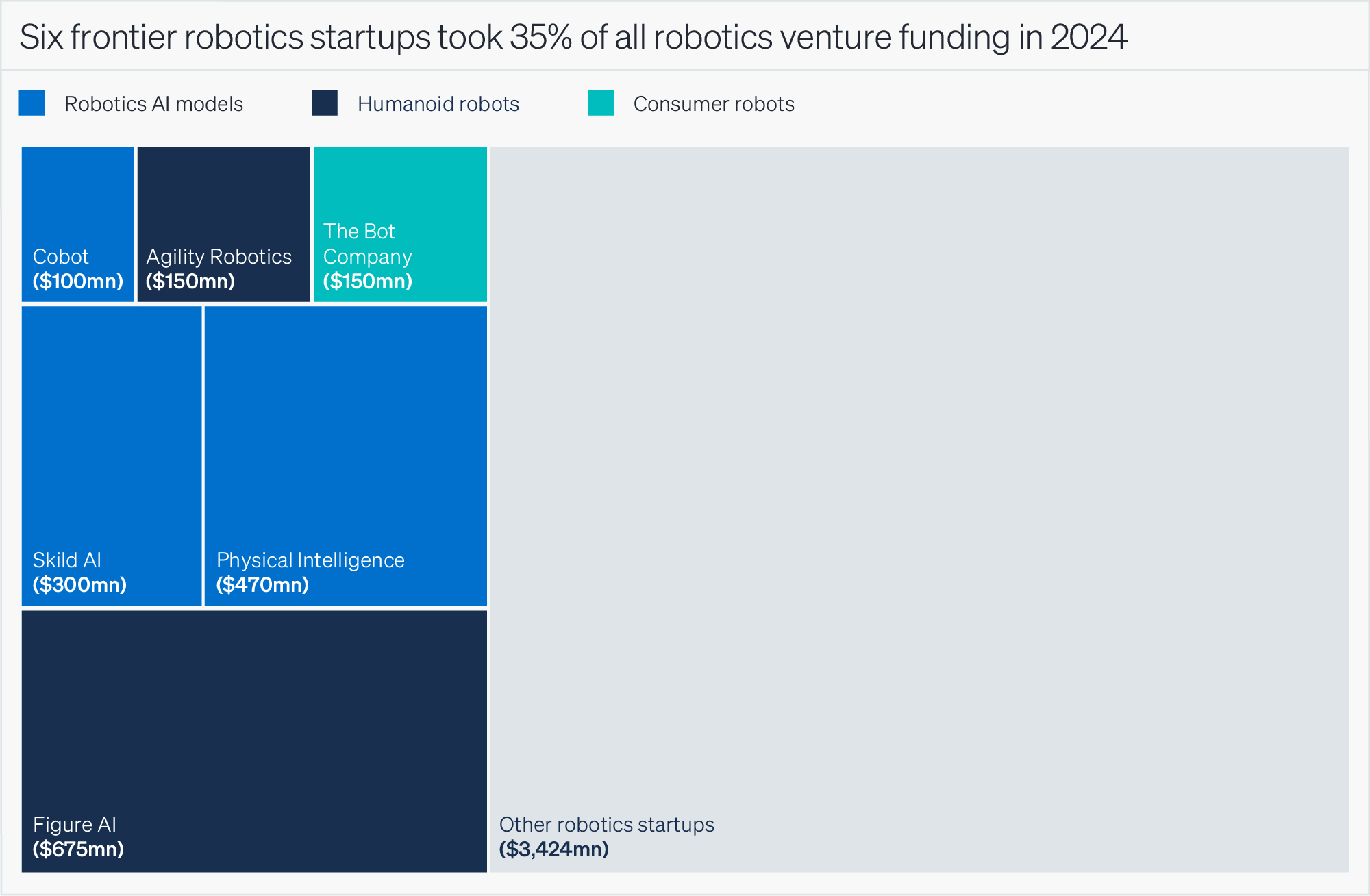

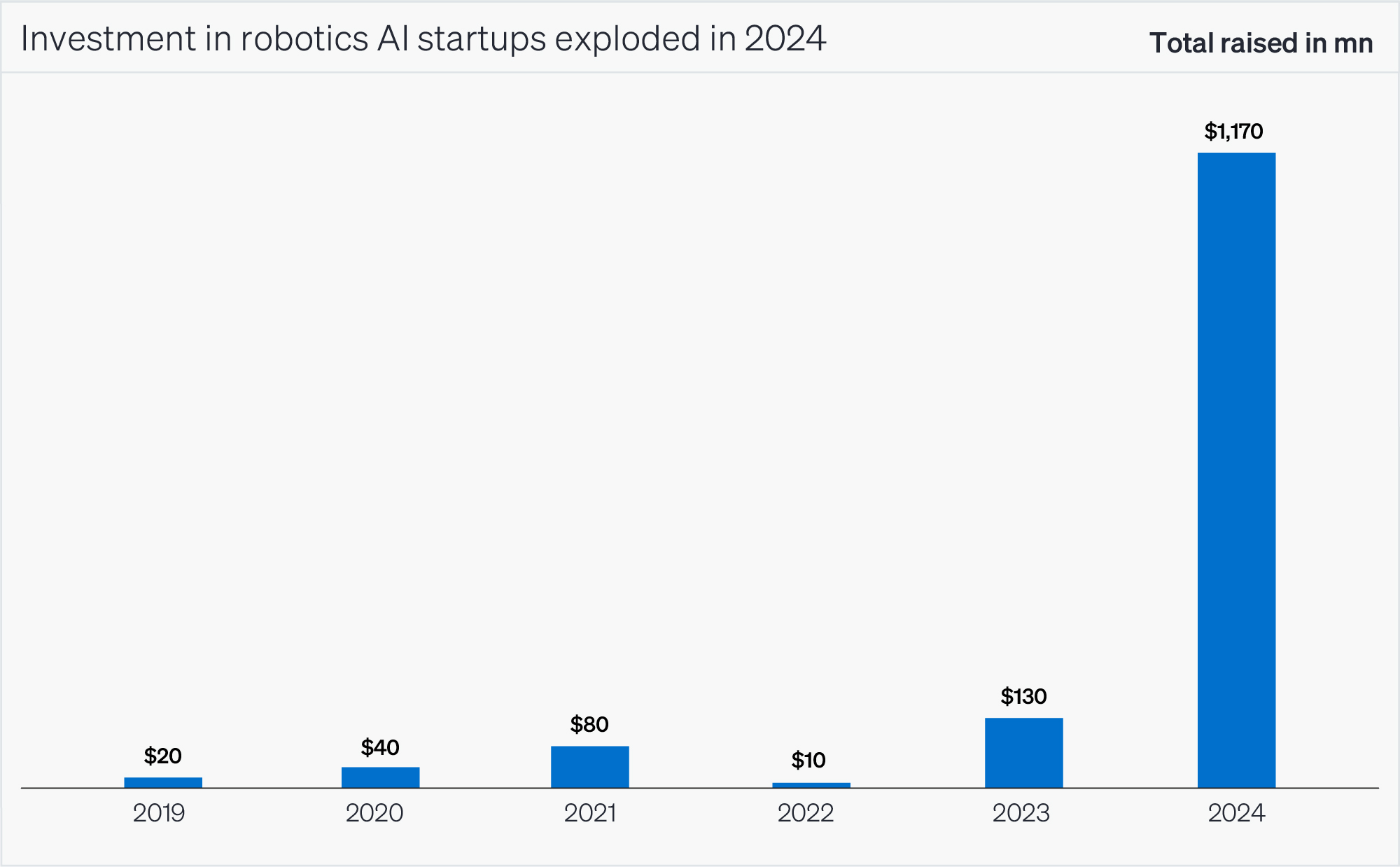

Much of the current robotics zeitgeist hinges on the idea that today’s AI can supply these breakthroughs and equip robots with the same type of flexibility we’ve come to expect from large language models (LLMs). In the past year, robotics funding shifted as investors made unprecedented bets on this frontier. Investment in just six frontier robotics startups accounted for over 35% of all robotics venture investment in 2024. Companies working on AI models for robots raised over $1bn funding in 2024—nearly 10x what they raised in 2023.

But the AI of today doesn’t automatically deliver new capabilities for robots. Instead, robotics companies will need to address both shortages and gridlocks in real-world robotics data in order to finally break the commercialization barrier. Only by addressing these systemic challenges can companies build mainstream-ready robots to operate in unstructured, everyday places.

We believe today’s cohort of robotics startups will continue to stagnate in pilot testing unless they can overcome these obstacles. This is critical because robotics lacks the structural data advantages that helped other AI fields advance—fields that still took decades of financial and technical investment to mature. While the potential in robotics is significant, we expect progress to be a resource-intensive process more akin to the long development of autonomous driving, rather than an abrupt shift.

We share our findings to help investors scope the robotics frontier and identify the most important challenges, risks, and paths forward. Breaking down our approach:

Section 1: Provides our framework for investors to orient themselves on the robotics frontier.

Section 2: Analyzes exactly what current AI can (and can’t) do for the robotics stack, and what it will take to build generalist robots.

Section 3: Explores the challenges investors should expect robotics companies to face in breaking through the commercialization barrier.

Section 4: Presents our perspective on investable opportunities.

Section 1. Open Worlds are the Robotics Frontier

The robotics frontier has always been about progressing from constrained to open worlds.

The best framework for investors to understand robotics is to look at how the evolution of software pushes robots out of factories and into new verticals. The ultimate prize is the ability to successfully operate in open worlds—places where robots encounter previously unknown things, locations, and people.

Software has been the greatest limiting factor in this progression. Though there have been immense improvements and cost reductions in hardware over the past 70 years, better software will enable robots to move beyond assembly lines and into everyday life. The earliest robots could only complete simple, precise tasks in highly constrained environments on factory assembly lines. As robots were equipped with better software for perception, navigation, and control, they could be deployed in marginally more fluid environments, like warehouses. Further improvements could push robots into truly open environments—homes and unpredictable public places, alongside people.

Constrained worlds: concentrated markets for mature technologies

Constrained, closed worlds are systematic and predictable places where proximity to people is unsafe or unnecessary. Factories where robots can work in fixed workcells, often literally caged for safety, are the prototypical constrained environment. Even today, these robots rely on well-established software paradigms that don’t involve any learning or adapting. They follow predefined tasks where everything around them is kept as consistent as possible.

Because of their relative simplicity, factories were the first environments where robots were deployed. The first industrial arm actually required no programming language—no real software at all. It was made by Unimation, the first robotics company founded in the 1950s. Unimation created the ‘Unimate’ heavy-duty arm which began earning its keep in 1961 by unloading metal castings from a die-cast press on an assembly line of the Ternstedt GM plant in New Jersey.[1] Unimation itself didn’t last long—its hydraulic arms were quickly out-competed by electrical ones. But since the 1960s, industrial robots have proliferated for routine manufacturing.

Manufacturing robotics is a mature, highly consolidated, and slow-growing space with little early-stage investment activity. Globally, $30–40bn is spent each year on purchases of new industrial arms. But this is a flat market, with sales growing at only 5% for the past six years globally and at less than 1% in North America.[2] [3] Most industrial robot arms are sold by four incumbents—ABB, Fanuc, KUKA, and Yaskawa—which together hold 75% share.[4] None are pure-play robotics companies—all are generalist suppliers of automation equipment that have been operating for much longer than the history of robotics. Because industrial robot arms are such a mature technology, there’s little startup activity in this space. Over the past decade, less than 10% of robotics VC funding has gone to industrial robots.

Structured worlds: active investment in current innovation

Outside of factories, there are opportunities for robots in places that aren’t as perfectly systematic as an assembly line, but are still highly structured. These structured world environments are often routine workplaces like warehouses, industrial sites, hotels, or office buildings. Here, robots must adapt a little bit but don’t face major changes to their surroundings or to the task at hand. They need some flexibility, but not full, open-world reasoning.

Ingrained structure helps ensure that robots can complete high-level tasks while adapting to minor changes. A robot arm unloading items from a palette must adaptively decide how to pick up various objects that are jumbled together. A mobile robot in a warehouse must navigate freely through aisles while avoiding people. Consistent surroundings help robots adapt reliably. In a warehouse, good lighting, standardized aisle spacing, and orderly workflows like one-way aisles help robots avoid collisions. In hospitals and hotels, ADA-accessible interiors with wide doorways and elevators allow robots to maneuver around people.

The market for structured world robots is smaller than the industrial manufacturing market, but faster growing. Robots for these environments see about 200k new annual installs, 30% of which go to warehouses.[2] These robots represent a $3.5–5bn annual revenue opportunity in terms of flat purchases. However, most are sold through subscription-based Robot-as-a-Service business models where customers rent robots, paying different rates for working and idle time. The size of this RaaS fleet is growing at over 20%, which is 4x faster than the industrial manufacturing market.[2]

Structured environments have been the realm of VC-backed robotics startups rather than older, self-sustaining incumbents like in the industrial robotics market. Half of such companies today have fewer than 50 employees.[2] Early stage investor attention has concentrated on this segment for the past decade, accounting for over 90% of robotics VC funding since 2014.

Structured world robotics represents many distinct applications across verticals, with varying degrees of technological maturity and market penetration. But across the board, their market penetration is <5% overall. So the potential for further growth is vast, with even cautious estimates placing it at over $300bn in revenue opportunity.

Warehouse robots

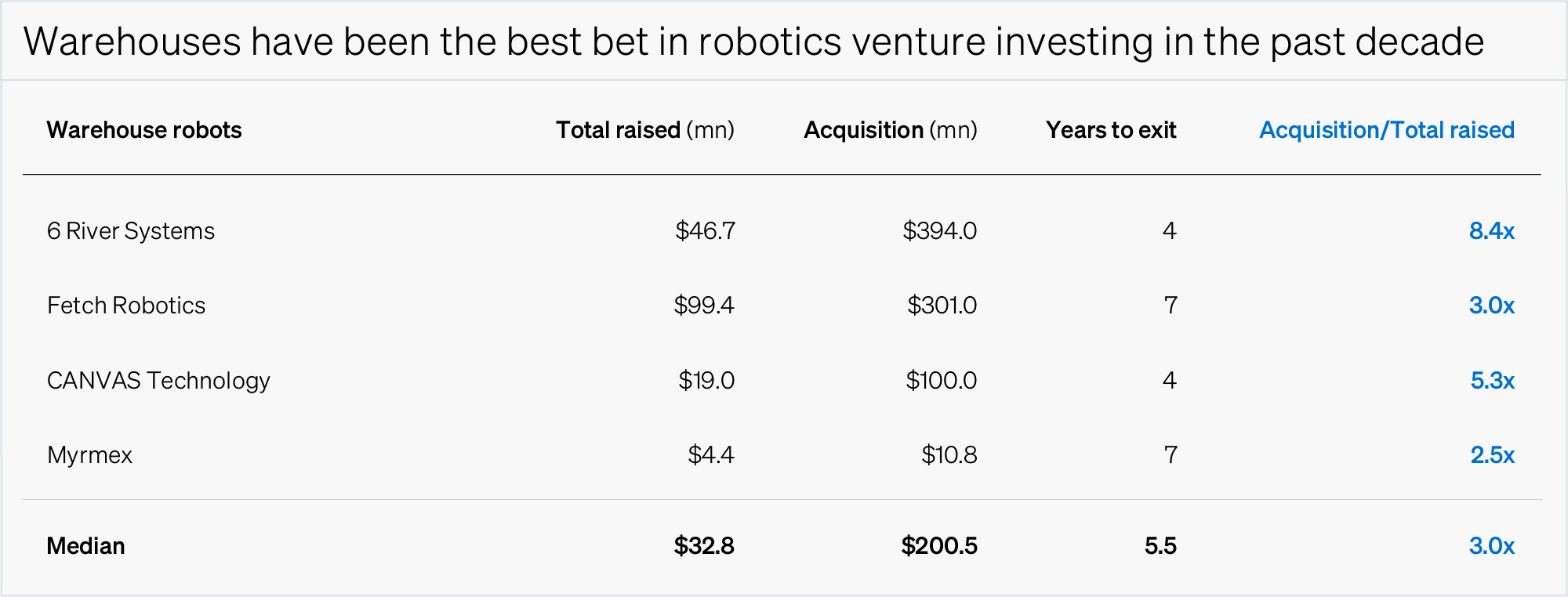

Warehouse robotics is one of the most commercialized applications of robots in structured environments today. In warehouses, robots require a minimal amount of additional adaptability to succeed, compared to busier places like hospitals or hotels. As a consequence, warehouse robotics companies have been the best bet for early stage investors in the past. Though returns are modest by VC standards, warehouse robotics has seen many of the most successful exits of robotics startups founded in the previous decade.

Because warehouses are one of the more established robotics verticals outside of manufacturing, robots also have a fairly established role to play. Most common are autonomous robotic carts, such as those made by startups like Robust.AI or Locus Robotics.[5] Autonomous carts are used to make independent deliveries across the warehouse, or follow a person as they pick items from shelves. Warehouses also make use of robotic arms for pick-and-place tasks like removing items from a palette or unloading boxes from a truck. Robots that can both move around and handle items are called ‘mobile manipulators’. For example, Agility Robotics frames its humanoid robot Digit—which is currently pilot testing in warehouses—as a mobile manipulator.[6] While Digit’s legged design makes it humanoid, Agility sees Digit’s underlying purpose as the next-gen way to combine the core functionalities of movement and handling of objects.

Robust.AI

Mobile robots can work alongside people in warehouses, like the Carter made by Robust.AI.

About 80k new warehouse robots are installed each year globally, usually rented via a RaaS business model.[2] This amounts to $2bn of new ARR coming online annually. And with only 5% market penetration in warehouses globally, this revenue opportunity could expand by tens of billions as demand for warehouse robotics accelerates.

Figure 1 Acquisitions of startups making robot arms for industrial or logistics applications, and those making warehouse robots. Though returns are modest by VC standards, they represent the most successful venture exits of robotics startups founded since 2014. Source: Pitchbook.

Autonomous vehicles

Autonomous vehicles are another application of robotics in structured environments that have seen early commercial success, capturing a small portion of expansive markets. Though a great variety of things happen on roads, they also have a lot of natural structure. Roads have rigid dimensions, consistent signage, reliable maintenance, and relatively strict behavior patterns. Because driving is so well-structured already, autonomous vehicles made initial progress very quickly. Serious efforts toward self-driving began with the DARPA Grand Challenges—government-sponsored research competitions wherein cars were autonomously racing through empty urban streets as early as 2007.[7]

These first research efforts have grown into several multibillion dollar companies. Challenge winner Sebastian Thrun went on to lead Google’s Self-Driving Car Project in 2009, which evolved into the $45bn robotaxi company, Waymo. Several other autonomous trucking and logistics startups have reached unicorn status, like TuSimple and Nuro. Tesla takes a different approach, gradually increasing the autonomy available to its large base of 5 million customers through Tesla Fully Self Driving, which received a major overhaul and performance improvement in mid-2024.[8]

While autonomous vehicles made relatively strong commercial progress versus other robotics applications, they still have a miniscule share of enormous markets. The rideshare and automotive markets are both hundreds of billions of dollars, and autonomous vehicles have barely begun to disrupt them. Today, autonomous driving companies are prioritizing software for their vehicles to adapt to rare situations like emergency vehicles, snow, cyclists, and road debris. This adaptability will allow them to operate in more geographies, enabling them to continue to encroach on legacy markets worth more than $500bn today.

Hospital delivery robots

Hospital delivery robots are another structured environment application—but one that has not seen as much commercial success. Hospitals have many routine workflows, like medication and linen distribution. They feature accessible interiors with wide hallways and consistent lighting. However, they are much more unpredictable than warehouse aisles. Hospital robots must be adaptable enough to politely get out of the way during an emergency, deal with blocked hallways, enter crowded elevators, and avoid mischievous people.

Hospital delivery robots have been in development for over 30 years. The first was built by Joseph Engelberger, who also founded Unimation, the first industrial robot company. After Unimation, Engelberger created HelpMate, a refrigerator-esque robot for delivering linens and meals. HelpMate entered revenue-generating pilots in 1991, with its robots rented out for about $12 in today’s money to compete with labor costs.[9] The company went public in 1997 with a fleet of ~100 robots and $4.5mn in revenue, but was acquired three years later by Cardinal Health and its robots were discontinued.[10]

In the 30 years since HelpMate, several companies have launched more and more advanced hospital delivery robots. These include startups like Aethon (2002), Savioke (2014), Robotise (2016), and Diligent Robotics (2017), as well as incumbent projects like Panasonic’s Hospi robots. These companies built robots with the same fundamental form factor as HelpMate (though Diligent Robotics added an arm) and sold them with the same subscription-based business model, but have not achieved broad commercialization.

Hank Morgan, Science Source; Lynn Nguyen

Hospital delivery robots carry linens, medication, or meals. They have been in development since the HelpMate robot (left) found its first paying customer in 1991. Today, robots like Diligent Robotics’ Moxi robot (right) use a similar form factor.

If these companies can break through the commercialization barrier, they unlock a significant opportunity. Robots providing courier services inside hospitals have a clear value proposition—they can return tens of thousands of hours to clinical teams per year to spend with patient.[11] Even a small fleet of delivery robots in every US hospital could represent $3–6bn of ARR. But hospital delivery robots’ long history of modest scale shows that the more adaptable a robot must be, the harder it is to commercialize.

Open worlds: the frontier

Open worlds are unpredictable places where anything can happen—in which robots encounter many possible tasks and interactions. The quintessential application of robots in open worlds is as consumer products in people’s homes—but it includes any highly variable place like sidewalks, airports, or shopping malls. In open worlds, robots need adaptable software that’s beyond the frontier of what works in orderly warehouse aisles or hotel hallways.

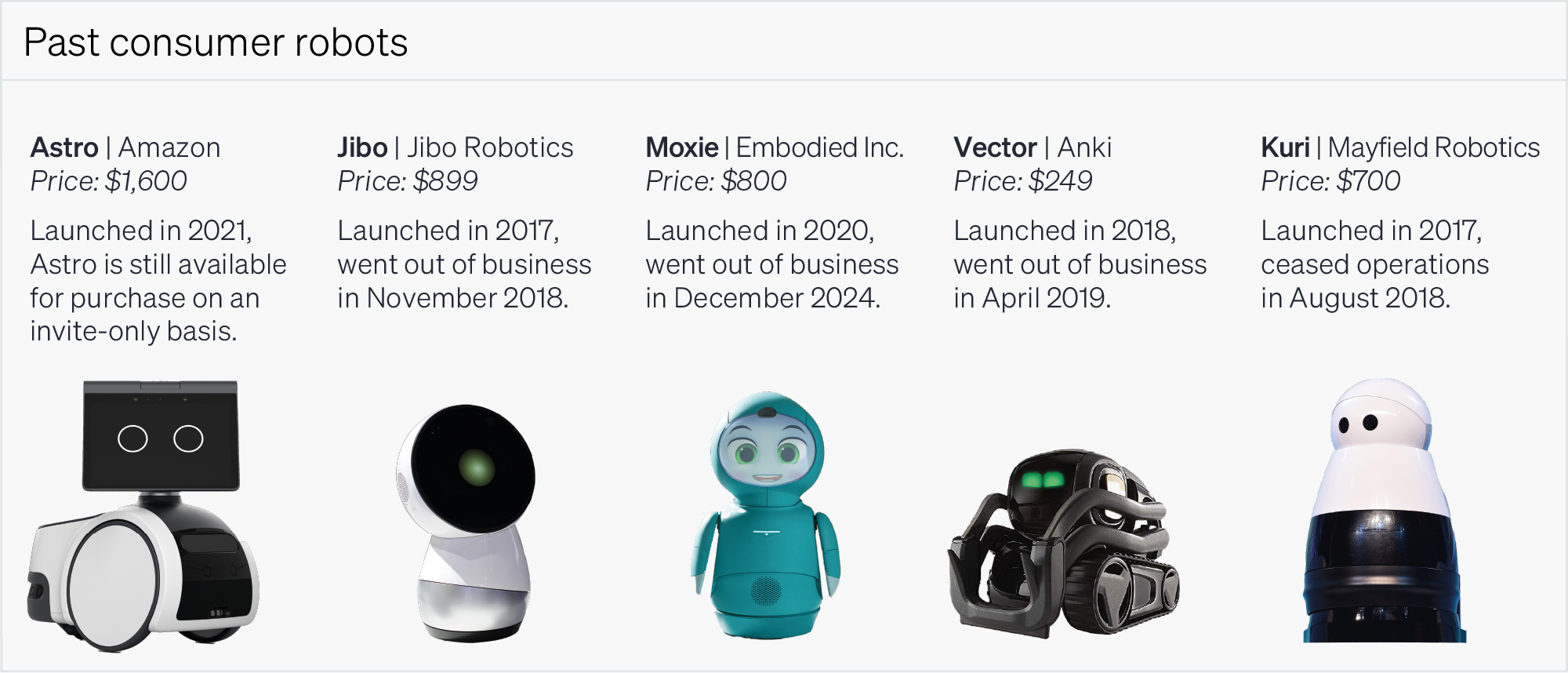

The challenge of building good robots for highly variable home environments means that almost no robots have succeeded in the consumer market. Many consumer robotics startups of the past decade have gone out of business without securing exits or further funding.[12] Among incumbents, Bosch and Amazon both incubated ~$1,000 home robots—Mayfield Robotics’ Kuri in 2017 and Amazon’s Astro in 2021—both since pulled from the market.[13] [14] These robots were meant to be generalists. Most were designed with a broad product surface area: games and entertainment, voice-enabled assistant services, audio or video calls, and video monitoring of pets or loved ones. In general, they didn’t gain traction because they weren’t uniquely good for these tasks compared to non-robotic solutions like home security systems and smart speakers.

Courtesy of Amazon, Embodied, NurPhoto, Seb Daly

Figure 2 Building good robots for the home is incredibly difficult. Consumer robotics startups and robots launched by large tech companies have both floundered. Of this set, the only one still available is Amazon Astro, which can be purchased on an invite-only basis.

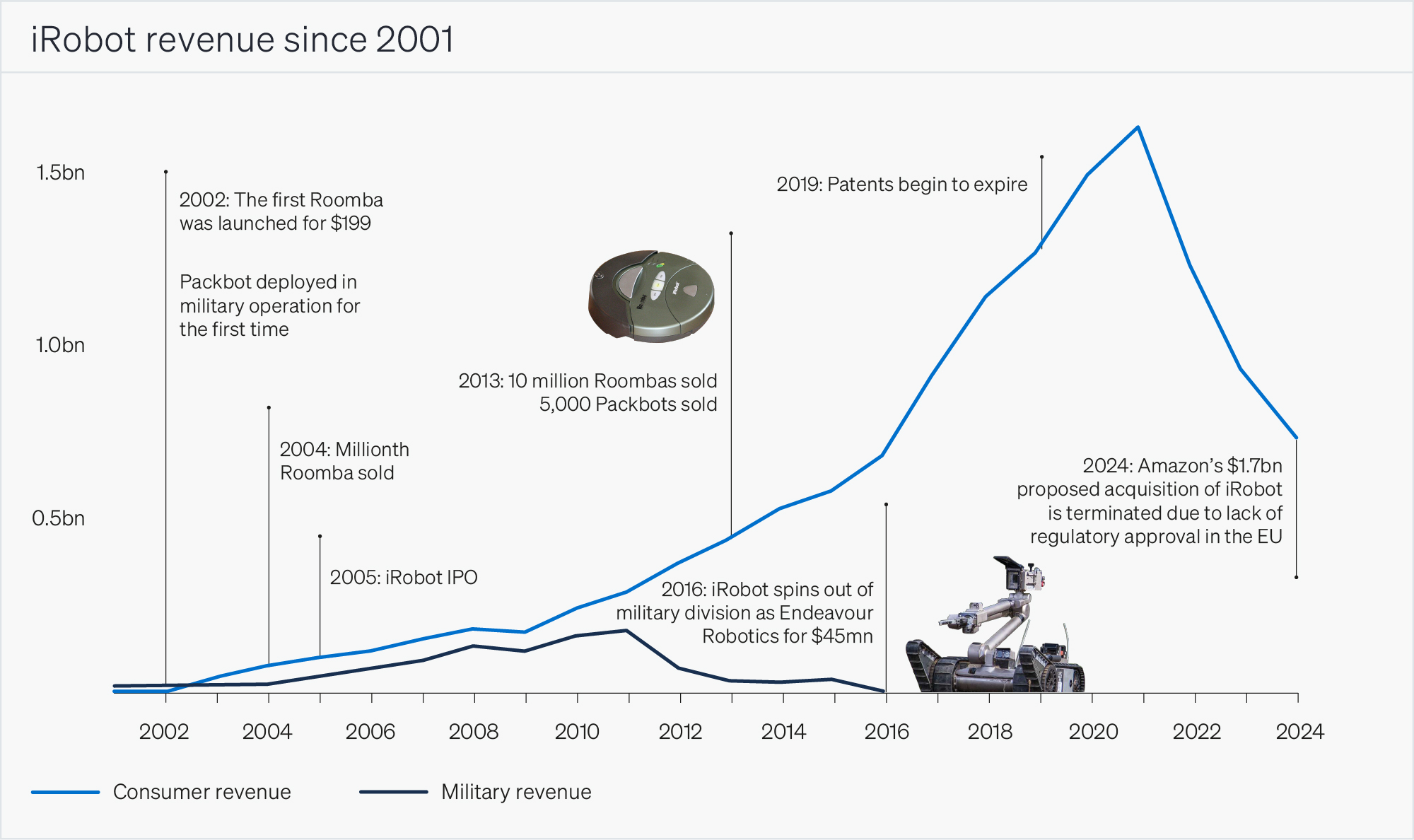

The one exception to the fraught history of consumer robots is robot vacuums, which were designed to be specialists, not generalists. Robot vacuums have succeeded as consumer products because they’re limited to a relatively constrained task and can largely ignore any potential disarray around them. They’re an established technology that has sold millions of units per year since iRobot launched the first Roomba in 2002. Today, 93% of all consumer robots sold are robot vacuums (most of the non-vacuums are toys and educational tools).[2]

Outside of robot vacuums, the consumer robotics market remains largely untapped as technological limitations have kept robots uninteresting to consumers, and unattractive to investors. But if its potential were fully realized, consumer-facing robots in homes and other everyday public places could become a huge market. People spend about $5bn every year globally on robot vacuums. There could be many other billion-dollar opportunities for specialist consumer robots. In fact, the Founder and former CEO of iRobot—Colin Angle—is launching a new home robot startup which raised its first round in December 2024.[78]

Investor attention is shifting to the frontier

While open world robotics has always been the frontier from a technical perspective, it’s only within the last year that venture investors have been willing to seriously back startups in the space. It’s now become the hottest investment area for early-stage robotics companies. Frontier robotics startups approach open worlds from a variety of angles. Some aim to build the next generation of home robots or to fulfill the vision of generalist humanoids. Others are focused on tackling the AI layer itself and building the software necessary to power open world reasoning.

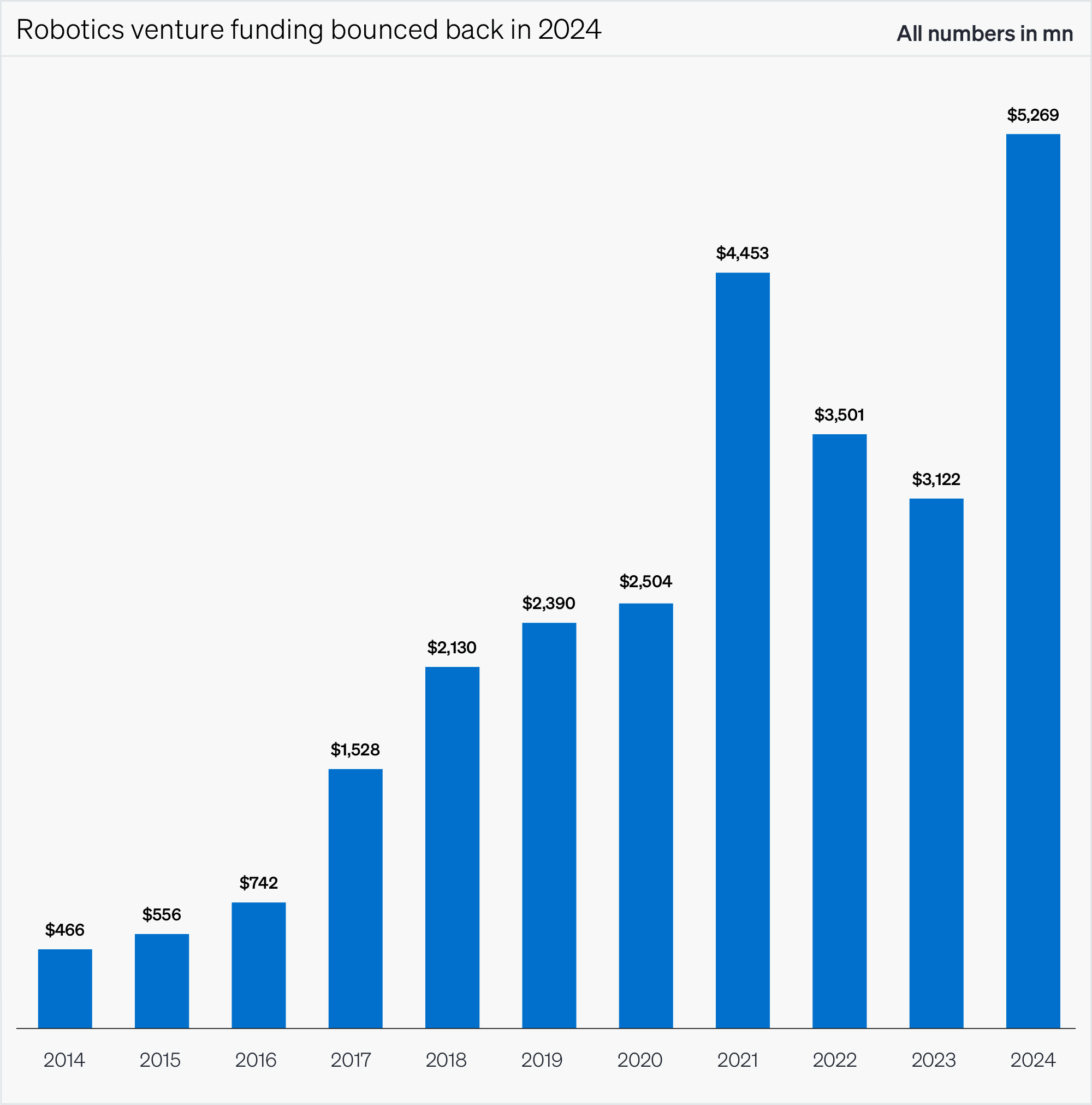

Figure 3 Robotics venture funding has primarily risen for the past decade. Funding decreased for two years after the 2021 secular peak in VC funding overall, but bounced back in 2024. Source: Pitchbook.

Megarounds raised by frontier robotics startups are changing the face of robotics capital markets. In general, robotics venture investment is increasing and becoming more concentrated. Funding decreased for a few years after the 2021 secular peak in VC funding overall, but bounced back in 2024 to a new high of $5.2bn. This recovery coincides with higher concentration. In 2021, the top decile of early stage robotics deals accounted for less than 50% of the total early stage robotics funding. But in 2024, the top decile of rounds accounted for over 80% of the total funding. Frontier startups explain this recovery and increase in funding concentration. Just six of them accounted for over one third of all venture funding for robotics in 2024. Two companies, Physical Intelligence and Skild AI, develop AI models for robots. The rest focus on open-world or generalist robots themselves.

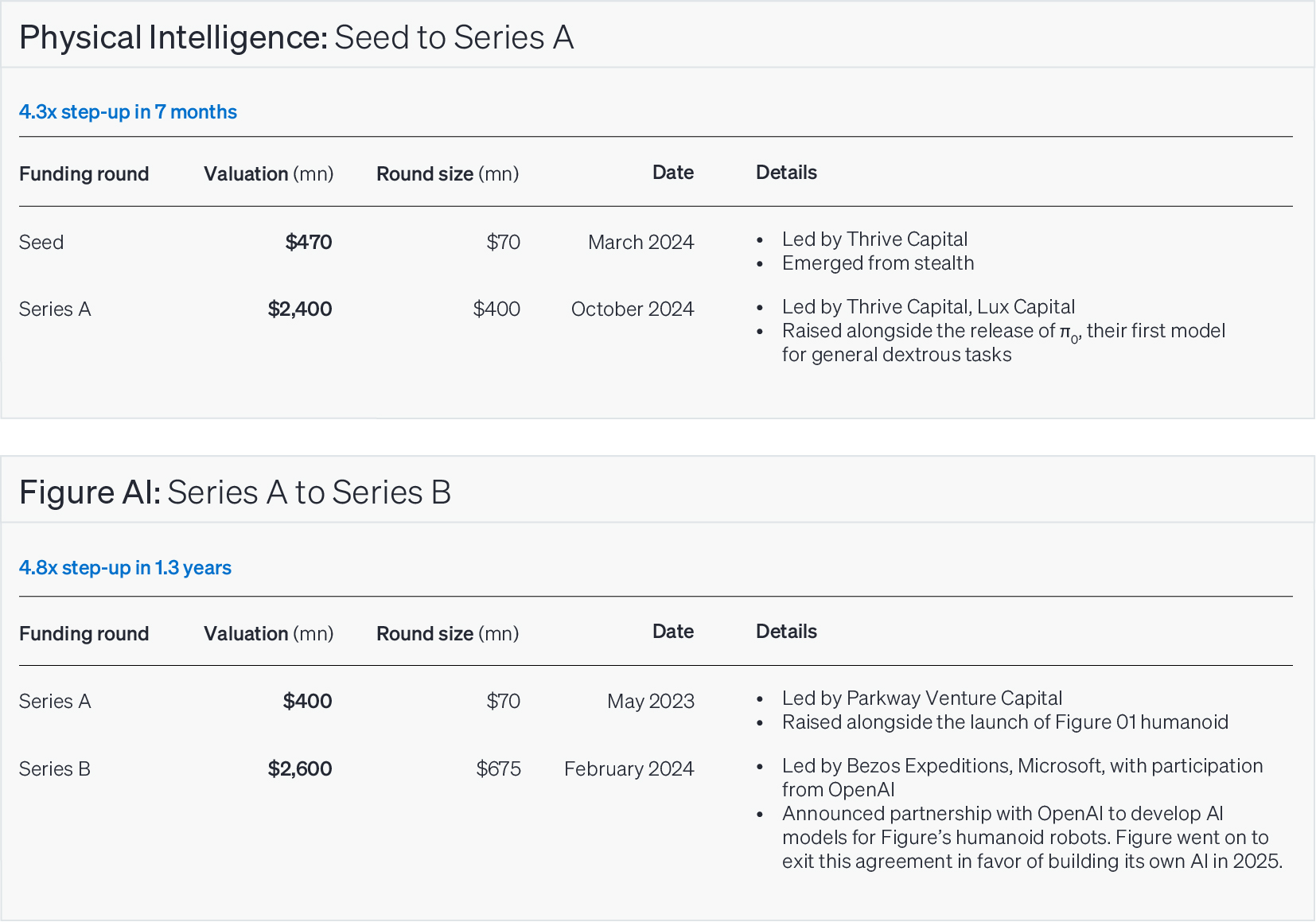

Valuations of these frontier robotics startups are also growing quickly. For example, Physical Intelligence increased more than 4.2x in value in the seven months from March 2024, when it came out of stealth, to October 2024, when it released its first prototype model. Humanoid robotics company Figure AI increased its valuation nearly 5x in less than a year.

Figure 4 Robotics investors are shifting their attention to the frontier. In 2024, just six early-stage startups accounted for one third of all robotics venture funding. Source: Pitchbook.

Figure 5 Valuation step-ups for Physical Intelligence and Figure AI. Among all US startups in Q2 2024, median seed to Series A step-ups were 2.8x in two years. Median Series A to Series B step-ups were 2.3x in two-and-a-half years. Source: [77] Pitchbook data.

How iRobot sold a million Roombas in two years

iRobot launched the first Roomba in 2002 and sold a million robots within two years, a feat since unrepeated by any robotics company.[16] Whereas many other robot vacuum companies built sophisticated, expensive robots, iRobot’s rapid early success came from building a maximally simple, affordable one.

Selling affordable, good products isn’t groundbreaking, but finding the right approach to do so in robotics is challenging. iRobot cycled through 14 failed business models from its founding in 1990 to the release of Roomba in 2002.[17] The company’s first business plan was ‘build a robot, send it to the moon, and sell the movie rights’. This and other failures helped iRobot accumulate the expertise needed for Roomba’s success: iRobot learned how to manufacture at scale from its partnership with Hasbro (failed business model #3), learned how to clean floors from making industrial cleaning robots (failed business model #8), and learned how to do simple navigation from making bug-like mine detector robots for the military (failed business model #11). In fact, iRobot’s military robotics business helped support the early years of Roomba with revenue from defense contracts. Once Roomba could hold its own, iRobot spun off this division for $45mn in 2016.[18] Today, iRobot’s military reconnaissance robots are sold by the sensor and equipment company Teledyne FLIR.[18]

The lessons from its failed business models led iRobot to create a product that was technologically years behind the frontier. Roomba’s early competitors included nascent mapping and navigation algorithms that added expense and user hassle. In contrast, early Roombas used simple sensors and random navigation to keep costs low. This allowed iRobot to make a product more than 10x cheaper than the competition.[17] The first Roomba was $199, which was intended to be just below the threshold at which you need to call your spouse before making the purchase.[19]

iRobot’s revenue has fallen in recent years due to the expiration of key patents and loss of market share in Europe and Asia. Amazon planned to acquire the company in 2023, but the acquisition failed after being blocked in the EU. However, the lessons of the Roomba’s rapid success are worthy of reflection.

It’s quite possible that the next consumer robotics company to sell a million units will use a sophisticated combination of very new technologies. But another strategy might be the Roomba approach—choosing the right problem and using tech years behind the frontier to solve it with an affordable, reliable product. Either way, iRobot’s remarkable, rapid commercialization is the seminal example of how product sense and early commitment to the right price point are essential to scale robots.

Figure 6 iRobot successfully scaled the Roomba incredibly quickly. The company committed to a simple technical approach that ensured the first Roomba was 10x cheaper than the competition. It also relied on another business line, making rugged military robots, to support Roomba’s early scaling. Source: iRobot public filings.

Section 2. Robots are Hardware Held Back by Software

From a roboticist’s perspective, hardware and software are equally important and interdependent. Robotics depends on integrating many mechanical and digital systems for robots to sense, think, and act in the world. From an investor perspective, we think hardware is nontrivial, but software is the more important barrier to commercialization today.

Hardware is already trending in the right direction—consistently getting better and cheaper. Fifteen years ago, the most cutting-edge home robot was the $400k humanoid PR2 (Personal Robot 2) made by the seminal robotics research company Willow Garage. When Willow engineer Melonee Wise left the company to develop more cost-effective platforms for Willow’s open-source software, she got the cost of similar robots down 10x to $35k by 2015.[20] Even the most advanced humanoid robots today are expected to cost half of the original PR2. Agility Robotics’ Digit is $150k to purchase and Elon Musk intends Tesla’s Optimus humanoid to cost only around $20k.[21]

With these hardware improvements, commercializing robots is all about connecting them to next-generation software so they can reach their full potential. In the last few years, LLMs have commercialized a new level of flexible workflows for abstract things like language and code. But these text-native models alone don’t automatically provide new capabilities for robots in the physical world. Companies working on AI for robotics face many technical challenges to give robots the versatility and competence we expect from AI today. They need to gather real-world robotics data with unprecedented scope and sophistication, while also developing a real-world robotics business to benefit from that data.

Robotics AI needs physical intelligence

Traditional approaches to deep learning in robotics devour time and resources, with no economies of scale. This is exactly what limited HelpMate Robotics’ commercial success with hospital delivery robots in the 1990s. Its robots relied on an ‘expert system’—a hard-coded logical flowchart of over 1,600 rules that needed manual updates every time a robot made a mistake.[9] This process meant no machine learning for the robots, and no economies of scale for the company. Now, robots can learn, but usually rely on distinct programs for specific tasks, based on either manually labeled data or many hours of manual human demonstration. For instance, it can take a handful of hours’ work to complete 300 to 400 separate demonstrations (and perhaps an overnight data processing session) for a robot to learn to rotate a Rubik’s cube or flip a pancake.[22] [23]

This approach doesn’t compound—teaching a robot one skill usually doesn’t make teaching the next any easier. Nor does it take advantage of what the robot has already learned. The labor intensity of data generation means that robotics datasets aren’t broad enough for robots to generalize. Narrow data causes robots to overfit, meaning small situational differences, like an object’s weight or table height, can lead to failures.[24]

A frontier alternative to single-skill learning is the foundation model approach. Models like LLMs trained on an enormous ‘foundation’ of data have the scope to jump between professional emails, poetry, and code. The idea is that a similar tool could allow robots to adapt and generalize in the physical world.

The prize to chase here is a generalist model for physical intelligence. In fact, one of the most valuable companies working on this problem today is simply called Physical Intelligence, and it’s valued at $2.4bn. Physical intelligence is our understanding of things and space in the world—the instinct we use to gingerly squeeze an overripe tomato, swirl clear liquid in an opaque cup, use a paintbrush or a paint roller interchangeably, and safely handle a hot drink. These tasks are hard for different reasons—adding a nut to a bolt requires precision, but handing someone a sharp tool requires consideration.[24]

In many ways, developing production-ready AI for physical intelligence is a much higher bar than today’s systems like chatbots, image generators, or code generation tools. Robots need real-time reasoning to make dynamic, fast decisions and operate safely. Additionally, errors and hallucinations are far more safety-critical for robotics compared to other AI applications. While hallucinations from language and image generators are frustrating, analogous issues in a free-roaming robot that works alongside people could be quite dangerous.

We don’t have a commercialization-ready AI model for physical intelligence today, but we have a good toolkit. Transformer architectures—like the ones that power LLMs—have already proven themselves capable in robotics applications. But architecture alone doesn’t unlock physical intelligence; instead, it provides good scaffolding for robotics companies to tackle data challenges.

Apptronik

The uncrossed bridge between bits and atoms

While transformers show promise, there’s no free lunch in the leap from abstract to physical intelligence. Robotics has not seen as much progress as other domains in a post-generative AI world because today’s best models still struggle with 3D reasoning.[25] LLMs are good at following instructions within the guardrails of a turn-taking text conversation, but can’t quite keep up with dynamic, fuzzy tasks in the physical world. They disappoint when it comes to realizing that ‘over there’ could mean a single shelf or an entire room, and that ‘the red cup’ might have moved since the last time it came up in conversation.[26]

LLMs don’t fully solve robotics problems because robotics data is much more complicated than text.[27] Even simple physical tasks could combine camera feeds with a robot’s sense of where its limbs are (from encoder sensors in its joints) or sense of touch (from force sensors in its hands). We’re still exploring the best way to wrangle and tokenize these multimodal inputs. For example, the extent to which robots could use computer vision alone, without a sense of touch, is still being explored.

Because of these limitations, most AI applications in robotics today are point solutions that focus on what models are already good at: words and images. They require a mediation layer connected to conventional robotic control systems to carry out actions. For example, DeepMind’s PaLM-E model uses an LLM to create high-level instructions that are then fed to a traditional, lower-level robot controller.[28] Microsoft’s LATTE model uses an LLM to adjust a robot arm controller based on natural instructions like ‘go faster’.[12] Robotics AI startup Cobot similarly uses a translation framework to convert language input like ‘we’re running low on supplies’ into precise commands that robots can execute.[29] These solutions enhance parts of the robotics stack that use language and images but don’t meaningfully cross the bridge between bits and atoms.[27]

Outside these point solutions, researchers have developed prototype full-stack robotics models that are good proofs of concept, but still quite limited. Many use turnkey vision-language models ‘grafted’ to a relatively tiny amount of robotics data. The result is technically a full-stack robotics model. However, the combination of lots of language data and little real-world data makes for a model with broad language abilities and narrow physical abilities.[30] [31]

Grafted models enable robots to understand more variations of the behaviors in their limited wheelhouse, but don’t help them learn new behaviors. A robot could parse that ‘pick up the soda can’ means the same thing as ‘pick up the shiny thing’. But the robot wouldn’t then know how to pick up a tissue, plug in a USB drive, or guess what to do if the soda can rolls off the table.[32] For example, the first Gemini Robotics model, released in March 2025, was trained on shirt-folding tasks using children’s shirts in a small range of colors. Impressively, it successfully generalizes to fold shirts of unseen colors, sizes, and sleeve lengths. However, it often fails to fold shirts that are rotated 180 degrees or presented face-down on the table, since neither situation occurred in its training data.[81]

A key lesson from these grafted models is that even their initial progress was incredibly resource intensive. Take Google DeepMind’s Robot Transformer models RT-1 and RT-2. They were trained by combining a vision-language model with a small amount of robotics data, representing just eight simple actions like ‘knock object over’.[31] But compiling enough examples of these actions took over a year of data collection from a fleet of 13 robots. The first Gemini Robotics models similarly required eight months of data collection from a team of 35 human operators. This model focused on a set of five more nuanced actions—including tying a shoe, stacking dishes, and inserting gears into a socket.[81]

Commercially viable AI for robotics must break this mold. It’s easy to recognize that solving the limitations of AI in the robotics stack would be an incredibly valuable enabling technology to push robotics forward in new applications. Early-stage companies and their investors are turning attention to this gap in the robotics stack.

The (robot) arms race for physical intelligence

An arms race took off in 2024 to bring the capabilities of generative AI to physical intelligence. Robotics AI companies raised over $1bn last year—4x more than the previous four years combined. Frontier startups are beginning to release models based on their initial progress. Robotics AI startup Physical Intelligence released its first model, called 𝜋0, in October 2024.[33] Humanoid company Figure AI released its first model, called Helix, in February 2025.[34] Both have a similar two-part architecture. The first part uses a vision-language model in conjunction with proprioceptive data about robots’ limb locations. This is then fed to another system (which Physical Intelligence calls an ‘action expert’ and Figure calls a ‘visuomotor policy’) that translates these inputs into new movements.

Tech incumbents are also reinvigorating their frontier robotics work. OpenAI is rebooting its internal robotics research team after previously disbanding it in 2021. Google DeepMind is investing heavily in robotics projects and has begun releasing Gemini Robotics models. Amazon acqui-hired robotics AI startup Covariant, which released its first model in May 2024 for pick-and-place robotic arms in warehouses.[35]

Other incumbents are focused on winning share with platform products for robotics development. NVIDIA is vying to do so with its Isaac platform,[36] an everything-but-the-robot ecosystem. Isaac is expansive already; it includes tools for embedded computing, training robots in simulation, CUDA-accelerated versions of familiar open-source software, and Gr00T, a research initiative to develop general-purpose robotics foundation models.[37] [38] Meta has also founded a new team within Reality Labs to work on robotics tooling. Meta isn’t reportedly interested in building its own robot and is instead focused on how it can leverage its existing work on VR to create a robotics development platform.[39] Hyundai’s Boston Dynamics is also developing a simulation and training platform for machine learning in robotics.[40]

Solving the AI layer for robotics can enable robots to take on previously impossible tasks and perform routine tasks in previously unworkable places. The market for all non-manufacturing robots today is less than a $10bn annual revenue opportunity. But better enabling software that increases adoption could expand this market by hundreds of billions. Similarly, fewer than 20% of US households have a robot vacuum. It could easily be worth tens of billions for a new robot to reach every US household with a budget for smart appliances.

Figure 7 Investment in frontier robotics startups working on generalist AI models increased by nearly 10x from 2023 to 2024. Source: Pitchbook.

What will it take for robotics AI companies to build foundation models?

The principal challenge facing frontier robotics AI companies is building representative datasets. This means collecting data that captures the full range of situations a robot will face—especially infrequent, but mission-critical ones. Outside of robotics, AI models can adapt and generalize because we’ve already gone through the process of collecting internet-scale datasets, and curating them to span enough rare and everyday situations. Likewise, we need an abundance of realistic robotics data to build AI good enough to expand robotics markets.

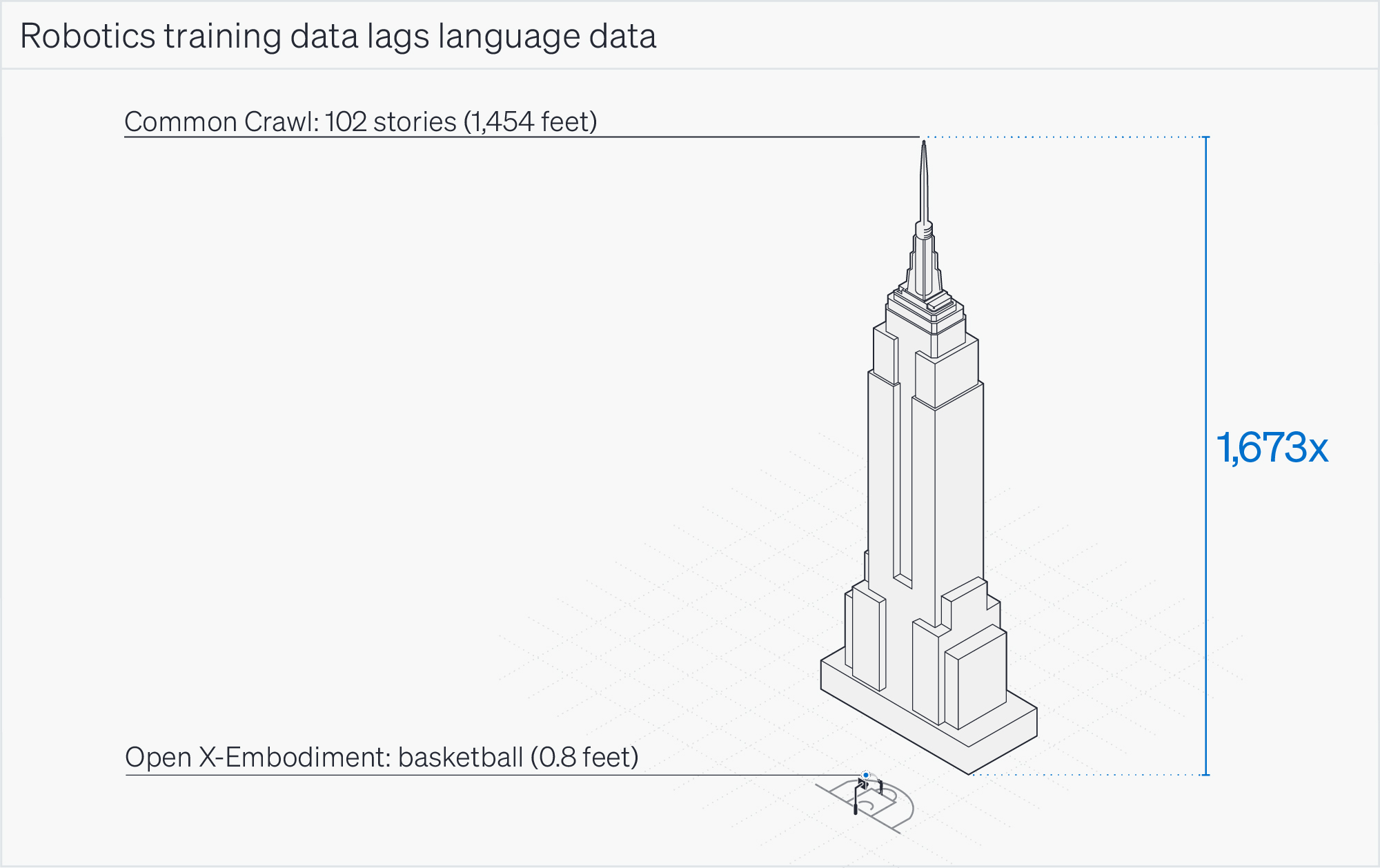

Figure 8 The scale of robotics data today lags the scale of data used to develop LLMs. Training LLMs relied on curating vast datasets like Common Crawl. Analogs to Common Crawl in robotics, like DeepMind’s Open X-Embodiment Project, are still many orders of magnitude smaller. Source: Positive Sum analysis.

Other AI applications have seen breakthroughs because they benefited from large amounts of naturally representative data. LLMs benefited from many rich, realistic sources of text—social media, Wikipedia, Github, and the digitization of books. When ChatGPT was released in November 2022, the size of language training datasets had steadily grown by 10,000x in a decade.[43] Much of this growth was achieved by the nonprofit Common Crawl, which maintains an immense open source repository of text. Commercializable LLMs would not exist without Common Crawl.[42] The best LLMs today rely on highly curated subsets of this internet-scale slush pile of language for the majority of their training data—like Hugging Face’s FineWeb, or EleutherAI’s The Pile.

Much like language, governments and other institutions have been gathering internet-scale autonomous driving data since the early 2000s.[43] The size of these datasets has also steadily increased, by 10,000x in the past decade.[43] By 2016, open-source driving dataset Oxford Robotcar was already 23 terabytes—about half the size of what it was rumored to take to train GPT4. That same year also marked Waymo’s first driverless launch on public roads. Since then, we estimate that Waymo has steadily collected over 130 petabytes of real-world driving data.

Outside of the special case of autonomous driving, robotics lacks the internet-scale data collection efforts that provided the fuel for AI in other applications.[24] [44] The best analog to Common Crawl or Robotcar today is DeepMind’s 2023 Open X-Embodiment Project (OXE), which combines small robotics datasets from 21 academic institutions.[45] But OXE is only about one thousandth the size of Common Crawl or Robotcar, and about one ten-thousandth the size of the data that we estimate Waymo has collected. It would likely take ~2,300 more years of robot ‘man-hours’ for OXE to reach the size of Common Crawl, and 20,000 more years for it to reach the size of Waymo’s real-world data.

Building AI for robots will require collecting much more data before we can curate a representative subset of the variances and corner cases robots will encounter in real-world situations. For example, much of the OXE data isn’t that realistic—toy wooden blocks appear 8x more often than kitchen tools. Already, researchers have curated a better subset of OXE, dubbed OXE Magic Soup.[33] These early efforts foreshadow that robotics AI companies are just beginning serious, systematic data collection efforts that will require several orders of magnitude more data before models can adapt well in the real world.

The gridlock of real-world robotics data

Robotics AI companies need representative data to build good software. But the only place to get it is from robots in realistic situations. However, the software and data limitations we noted previously mean that it’s challenging to build a robot that can even be deployed into the real world to collect meaningful data.

There are multiple strategies to break the stalemate. Some companies are prioritizing data first, and deploying robots second. They are focusing resources on releasing models trained with a fleet of in-house robots. For example, startup Physical Intelligence is collecting its own data from an in-house fleet of robots practicing various tasks—like unloading washing machines. It raised $470mn since its seed round in March 2024, and has already collected 10,000 hours of its own robotics data (about one year of robot man-hours).[33] Figure AI’s Helix model was similarly trained on 500 hours of data from manually operated robots.[34]

Another strategy is to prioritize deploying robots first, and models second. Some companies, like Cobot, aim to build robots that can operate at a level of quality that’s nevertheless sufficient to drive sales. The business doesn’t need frontier AI models, but would benefit from them as soon as they are created.[23] [46] The idea is that as soon as a robot is good enough to be worth paying for as a real product, realistic data becomes a byproduct of revenue.[47] It might take 2,300 more years of robot man-hours to make a Common Crawl-sized robotics dataset, but we estimate that if every Walmart in America had just one robot restocking the shelves for just one hour at night, they would reach this in less than two months.

Simulation and synthetic data will do the heavy lifting for robotics AI companies building datasets and training new models, but they won’t solve the last mile in open worlds. Robots can learn a lot in simulation, but still need real-world experience to get the details right. This is known as the ‘Sim2Real training gap’, in which behaviors trained in simulation don’t quite hold up in the real world. For example, Agility Robotics found that humanoids trained to walk in simulation would lose their balance in the real world because of variations in the grippiness of real ground they couldn’t simulate.[75] Simulation is also better at representing simple, structured places. For example, Robotics AI company Cobot reported that its robots learned to navigate a warehouse environment almost entirely in NVIDIA’s Isaac Sim simulator.[38] But simulating a well-lit, clean warehouse is much more reliable than trying to simulate the endless chaos of a busy kitchen. So real-world data will remain especially important for frontier robotics companies working on open-world applications.

Autonomous driving foreshadows what it will take to solve physical intelligence

For investors to predict the path to future success in AI for physical intelligence, it’s helpful to understand how data challenges were solved in the specific case of autonomous driving. Autonomous vehicles—especially robotaxis—provide a good peek into the future of generalist robots because they’re ahead in both the transition towards generalized AI, and commercial presence in consumers’ everyday lives.

Just like with physical manipulation tasks for robot arms, previous approaches to AI in self-driving involved distinct systems for single tasks like lane tracking, object detection, navigation, and the human interface.[43] Today, companies are prototyping full-stack alternatives that combine all these functionalities into a single system. Tesla recently shifted to this approach with the Full Self-Driving (Supervised) v12 release,[48] replacing an older system with a single end-to-end neural network.[49] Waymo also unveiled a prototype full-stack model called EMMA (End-to-End Multimodal Model for Autonomous Driving) in 2024. This model generates brief driving sequences based on natural language input.[50]

Curating representative, real-world data is key to success for autonomous vehicle companies—self-driving wasn’t built from racetracks or closed city streets. Companies have developed this real-world data flywheel in different ways.[51] Waymo’s robotaxi service in San Francisco gathers data from near-complete autonomy in limited places. Tesla collects data from partial autonomy across its many customers in many locations. But both of these strategies involve natural access to real-world situations.

Autonomous driving companies have relied heavily on simulation, which has proven to be an accelerant, but not a full solution for real-world adaptability. Waymo and Cruise both relied heavily on simulation tools to parallelize training—Waymo logging 3mn simulated miles per day by 2016.[52] But robust synthetic data and simulation efforts haven’t eliminated the need to gather realistic data from real deployments.

Zuma Press, Waltarrrrr

Stanley (left) was the winner of the 2005 DARPA Grand Challenge created by Sebastian Thrun and the Stanford Racing Team. Thrun went on to have a key role in leading the Google Self-Driving Car Project, which has since become the $45bn+ company Waymo (right).

Curating corner cases is the current bottleneck in autonomous driving

Building self-driving cars involves the same challenge as building general robotics models: gathering and curating large, representative datasets. Today, autonomous vehicle companies have an abundance of real-world data that dwarfs language and text datasets. For a long time, self-driving technology needed a brute-force data collection approach to improve performance.[53] By today, Waymo has driven 20mn autonomous miles on public roads, which we estimate amounts to over 130 petabytes of data—about nine Common Crawls. Its Jaguar I-Pace cars generate more than a terabyte of log data per hour—the size of Open X-Embodiment in a single day of driving. Tesla has similarly collected data from over a billion miles driven by five million vehicles.[8]

Now, autonomous car companies are focused on curating representative data, not simply collecting more of it. They throw out most of the data they collect in order to filter for rare, critical situations among the noise of monotonous, everyday driving. Waymo now deletes data it deems repetitive and prioritizes snow, emergency vehicles, and cyclists.[54] In fact, Waymo is planning several ‘road trip’ deployments to places like Tokyo, where cars will be driven manually to expose the self-driving system to new environments and weather conditions.[55] Like Waymo, self-driving truck companies Aurora and TuSimple also discard most of the data they collect, save for examples of unusual situations, like debris on the freeway.[54] Tesla’s autonomous driving work also hinges on curating the right balance between common and rare events.[57] Only about 1/10,000 of Tesla’s miles driven are useful for training models.[56]

Robotic cars took 20 years and $200bn. Will other verticals be the same?

The road from inaugural data collection efforts to commercial products in autonomous driving took 20 years and $200bn. It really began in 2004 with DARPA’s first Grand Challenge, a $1mn prize to autonomously navigate 150 miles of the Mojave desert. In the first year, no vehicle accomplished more than 5% of the course. But by 2007, Grand Challenge teams were reliably completing both all-terrain and urban races.[7]

After DARPA threw in the first few million dollars of prize money, investors and car companies contributed nearly $200bn of additional funding over the next two decades. During this time, both automotive and tech executives made a swath of predictions for the arrival of self-driving, anytime from 2017 to 2030.[58] Finally in 2020, Waymo opened its fully driverless service to the general public in Phoenix, and then in San Francisco in 2024.

Autonomous cars have been technically capable of navigating urban streets since the early 2000s, and have been carrying people on point-to-point trips since the mid 2010s. But it took several more years for them to become safe and performant enough to launch a generally available service for consumers. We think that today’s AI for robotic physical intelligence is like autonomous driving in the early 2010s. It’s likely that much more time, money, and grit is necessary to make general robots into commercial products.

There are both reasons to be optimistic and hesitant that the data problem in robotics can be solved more quickly, and cheaply, than it was for autonomous driving.[23] We have wildly better model architectures and machine learning infrastructure today. But lack of historical, internet-scale data collection creates meaningful friction. If other applications of robotics follow the exact same path, then we estimate it could take 7–10 years, and tens of billions of dollars, to bring them into our homes and everyday lives.

Section 3. Pilot Testing Does Not Guarantee a De-Risked Robotics Business

As we’ve shown, investors can assume that most robots are satisfactory hardware held back by unadaptable software. Investors should also understand that the symptoms of these software-driven limitations bring distinct risks. In particular, a robotics company reaching the phase of pilot testing should not signal the same de-risking point that it might for investors familiar with SaaS.

For most hard tech companies, launching a revenue-generating pilot is a critical de-risking point for investors. This is not the case for robots. Robotics companies that find early pilot customers quickly may still struggle to scale at the rate venture capital typically requires. Starship, a relatively successful sidewalk delivery robotics company, took 10 years and $218mn of VC funding to grow to approximately $20mn in revenue. Even robots launched by tech incumbents with distribution, funding, and an existing customer base have run up against the post-pilot commercialization barrier. Amazon has incubated two consumer-facing robot products in the last five years—the home robot Astro and the sidewalk delivery robot Scout—both of which have been dropped after years of small deployments (Astro is still available by invite only).

Pilot testing retains more risk for robots, relative to other technologies, because piloting is part of product development. No robot can be prepared for real-world situations in a pristine lab. Robotics companies must pilot early to collect representative data about how robots should handle a variety of realistic situations, not just to evaluate ROI.

One might have naively expected low-hazard robots to be an easier problem than other hard tech. But investors should not underestimate the way the extreme unpredictability of unstructured places can erode a robot’s commercial horizon.

Why did sidewalk delivery robots fail to capture a $10bn opportunity in the pandemic?

A pertinent story about the riskiness of robot pilot testing is why sidewalk delivery robots didn’t take off during the pandemic. In the 2010s, it was expected that sidewalk delivery robots could capture material share in last-mile food delivery by 2025.[59] [60] [61] A common bet was that even if sidewalk robots didn’t completely revolutionize the last mile, they would certainly arrive before robotaxis. It wasn’t irrational for investors to expect that small sidewalk robots could outpace full-size autonomous vehicles: sidewalk robots have many lower technical hurdles, cheaper inputs, lower safety requirements, and less fear or resistance from users.[62]

By 2019, a cohort of over a dozen startups had raised $1bn—all with similar ‘cooler on wheels’ robots. They were joined by three corporate projects: the Amazon Scout, FedEx Roxo, and Postmates Serve robots. Then, March 2020 brought the tailwind of the century for these companies. Sidewalks emptied of crowds and demand for short-haul food delivery skyrocketed.

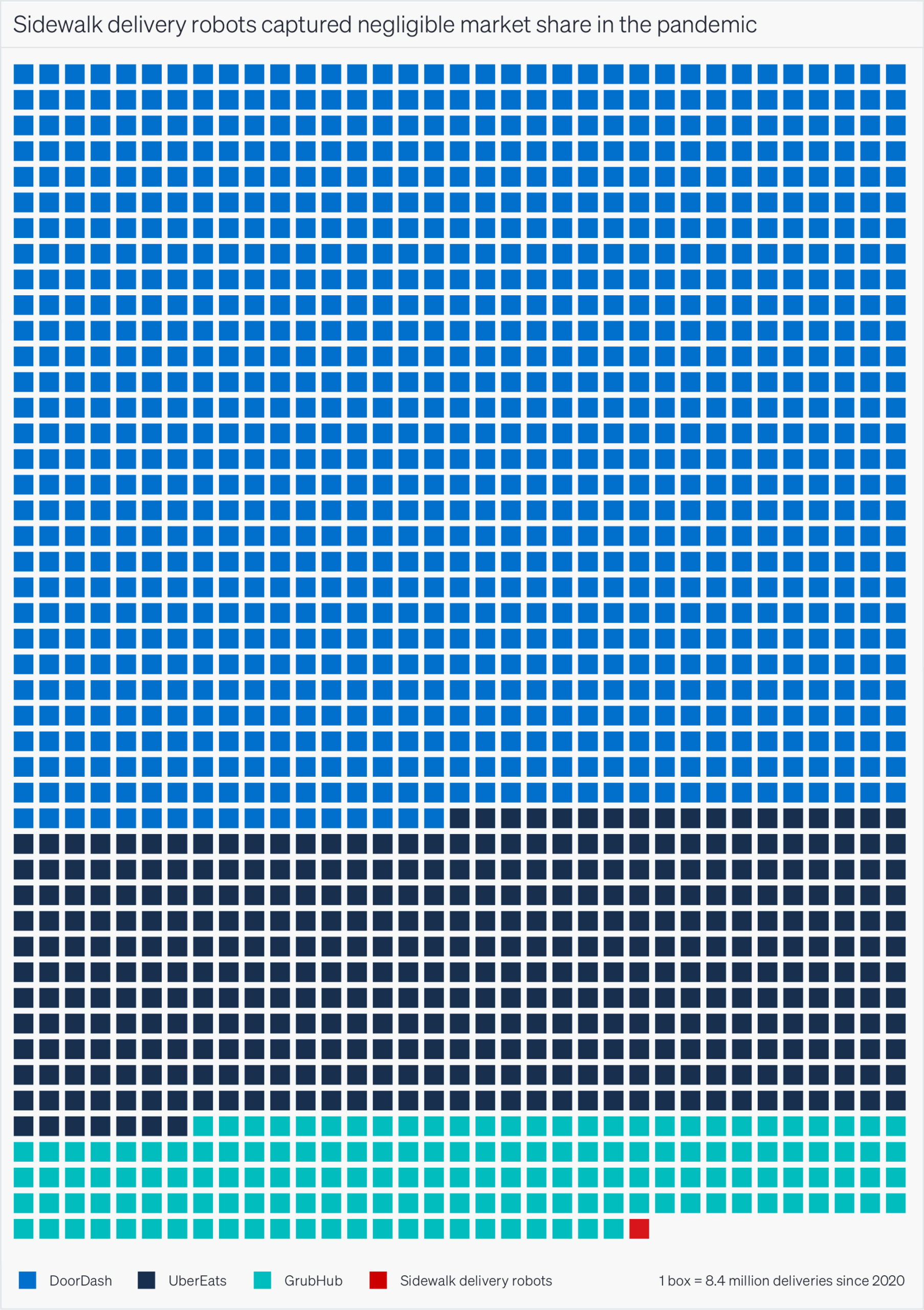

UberEats and DoorDash both sustained 100%+ revenue growth for the first two years of the pandemic, and grew their user base by over 20mn people.[74] From 2019 to 2023, the food delivery market grew from $3bn to $13bn—a $10bn opportunity.

Pexels

Sidewalk delivery robots made by Starship Technologies.

But sidewalk delivery robots captured essentially none of this $10bn prize. All sidewalk delivery robots completed less than 0.1% of the total food deliveries since the beginning of the pandemic. Many of the dozen-plus original sidewalk delivery robotics startups have folded or pivoted. And this wasn’t for lack of capital, as these startups doubled their funding during the pandemic. Of the corporate projects, both the FedEx Roxo and Amazon Scout robots were canceled after several years of pilot testing.[63] Postmates’ robotics division was spun out as Serve Robotics after the Uber acquisition and is operating with ~$2mn of revenue from its small fleet of 48 robots.

The startups that still operate today have remained at modest scale in limited geographies. The most successful to date is Starship Technologies—which was founded in 2014 and rapidly reached its first pilot in the UK within a year. Starship’s US growth strategy has been to focus on college campuses—slightly more structured environments where sidewalks are more orderly and predictable than urban downtowns. In 2019, Starship announced its plan to have robots deployed on 100 US college campuses within two years.[64] It raised $178mn towards this goal but only reached an additional 16 deployments in that time period. Today, it operates on 55 campuses, just 1% of US colleges.

Sidewalks are open worlds

The fundamental challenge faced by sidewalk delivery robot companies is that sidewalks are open worlds. Compared to roads, sidewalks are the Wild West. Roads offer a controlled, standardized environment with traffic rules, consistent signage, and reliable maintenance. In contrast, sidewalks include wheelchairs, strollers, children, dogs, narrow turns, first responders, and sometimes cars turning right on red—all of which causes serious trouble for delivery robots.[65] [66] [67] It’s true that sidewalks have a lower safety barrier than roads. But their frequency of corner cases is much higher, even if the stakes are lower. This is why companies have fallen back on the simplest, most structured sidewalks they can find: walkable European towns in the summer, arid US cities with little pedestrian traffic, and well-groomed college campuses.

The story of sidewalk delivery robots should warn investors that even with plenty of funding and market-transforming tailwinds, the unrelenting complexity of open worlds makes robots risky. Delivery robot companies didn’t have the data to prepare their robots for all the disorderly situations they encountered, so they couldn’t break through the post-pilot commercialization barrier, even with plenty of demand. They show that pilot testing is only the beginning of product development for robots meant to coexist with people.

Figure 9 Taken together, all sidewalk delivery robots completed less than 0.1% of total food deliveries since 2020. Source: [74], Positive Sum analysis.

Commercializing humanoid robots

So far, we’ve outlined our framework for how software defines the robotics frontier and plays a key role in robots’ ability to break through pilot testing and succeed in new markets. Investors can use this framework to form expectations about new opportunities.

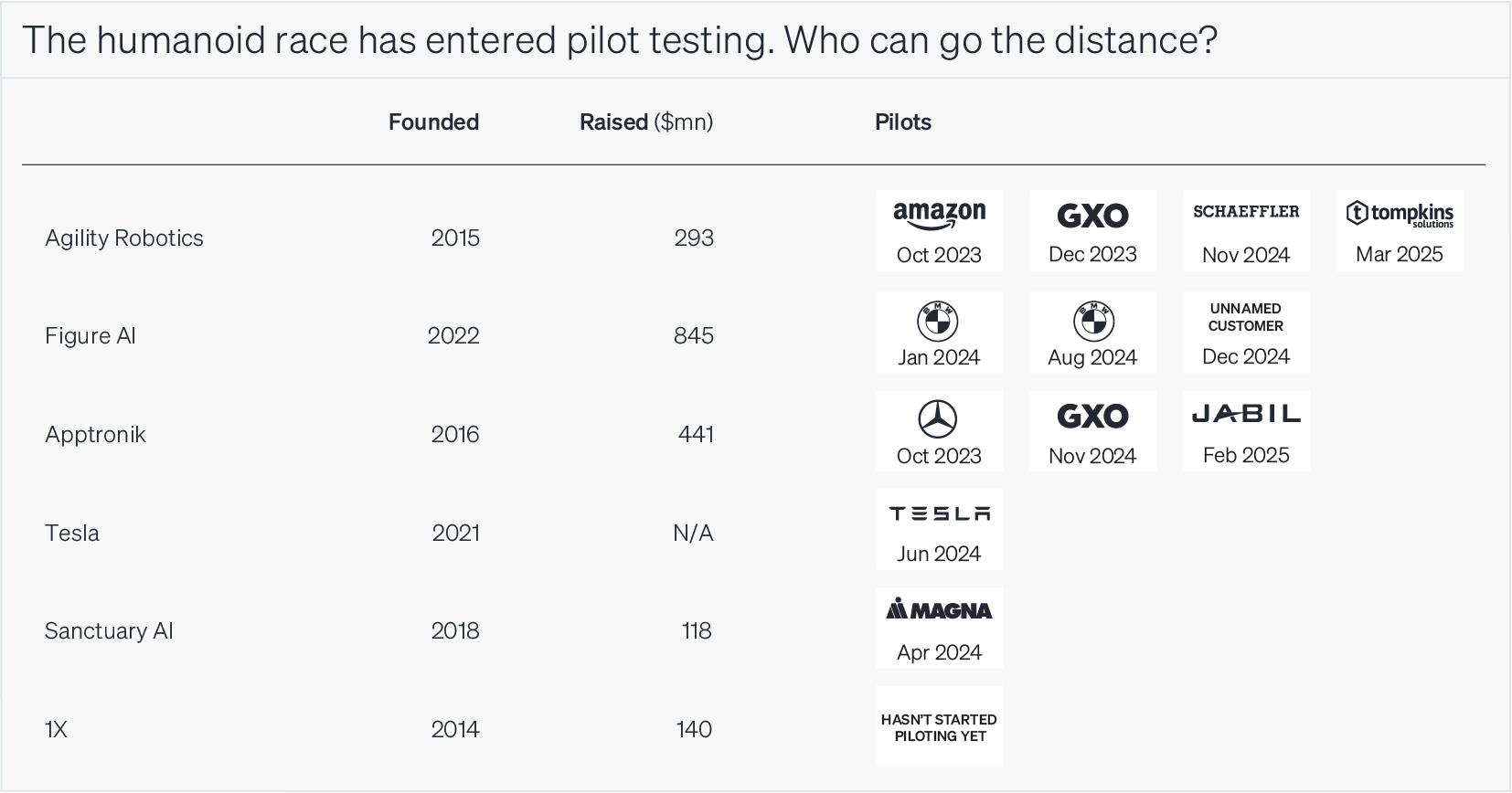

Perhaps the hottest space today where it’s important to have realistic expectations is humanoids robotics. Humanoids are buzzing and well funded. Two startups—Apptronik and Figure AI—have already achieved unicorn status. Figure has raised the most money of any humanoid company, with $845mn of funding that amounts to 30% of US humanoid funding in the last five years. The company is currently in talks to raise an additional $1.5bn at a nearly $40bn valuation, which is a 15x increase in value since February 2024.

It can be hard to discern the line between innovation and spectacle with humanoid robots. They naturally capture our attention because they look like us. When a humanoid robot completes a task, people often make generous assumptions about how much it mirrors our underlying abilities. A demo video of a humanoid opening a door might seem to imply that the robot could open any other door, or the same door with a different handle, or a refrigerator, but this likely isn’t the case.[68] Humanoids are notorious for stagecraft demo videos with sped-up footage, remote control, or pre-scripted movements that exaggerate their capabilities.

But humanoids aren’t all stagecraft. Within the past year, several humanoid robotics companies began their first deployments with paying customers. Figure and Sanctuary AI both completed pilots in automotive manufacturing within the last year. Figure has reportedly engaged a new customer, but hasn’t yet disclosed their identity.[69] Logistics company GXO has begun pilots with fleets of Apptronik’s Apollo and Agility Robotics’ Digit, where the Digit fleet earns $30 per hour, per robot.[70]

This milestone means humanoid companies have just begun an important and early phase of their product development.[71] In pilots, companies begin the process of learning lessons from how their robots function in the real places that they could never encounter in a pristine office, or even in simulation. As in other robotics applications, these pilots will be critical to generate the real-world data required to drive software improvements.

Lack of open-world AI is an especially acute bottleneck for humanoid robots because they are envisioned as generalists—able to accomplish a human-like variety of tasks in everyday environments. For a humanoid to be as good at doing dishes as it is at moving pallets around a warehouse, it will need incredibly reliable open-world reasoning. Building generalist AI capable of powering humanoids as a horizontal product will require data spanning a vast range of contexts and situations.[73] Humanoid companies are increasing their focus on this problem. Apptronik announced a strategic partnership with the Google DeepMind robotics team, alongside the release of its first Gemini Robotics models[79] [80] Figure AI had a similar partnership with OpenAI, which it has since ended in favor of building its own model.[15]

Outside of the overarching software challenge, there are still many challenges to address through early deployments of humanoids.[72] One thing to tackle is safety around human proximity—humanoid pilot tests today are taking place without people nearby. Another thing is speed and balance. Even the fastest humanoids run at only 20% human speed. To get faster, humanoids would benefit from better control and balance systems for things like slippery ground, carrying unbalanced boxes, or even swapping out their own batteries.[73] [75] These are simple examples in a long list of tricky problems that humanoid robotics companies will need to address as they continue pilot testing.

Humanoids are the Formula One of robots

Developing humanoid robots will be a long road so investors should be cautious about expecting rapid commercialization. Most investors should not jump on humanoid robotics companies unless they’re comfortable investing in a product with a long research and development horizon. However, there may be a silver lining for the robotics industry as a whole, as humanoids could yield dividends for more readily commercializable technologies.

Humanoid robotics companies are like the Formula One teams of robotics—they’re prioritizing a unique form factor at the expense of cost. Formula One teams allow car companies to ideate with a big budget and room to experiment. The goal isn’t to make these cars everyone’s daily driver. But plenty of Formula One tech has made it from racetracks to regular cars. This role as a research incubator is already held by robotics company Boston Dynamics. Famous for its sensational YouTube demos, it has been a subsidiary of Hyundai since 2021. Boston Dynamics develops the Atlas humanoid, which it sees as a research project intended to test the limits of what’s possible for other robots.[76]

Ruthless pursuit of humanoids could change the landscape of robotics enabling technologies for the better. Humanoids push the boundaries of robots’ motion control, balance, obstacle avoidance, battery life, and safe human collaboration. Building actuators, sensors, and algorithms that improve these things for humanoids will make it much easier to develop new robots in general. It may become simpler for more smart people to start robotics companies and work to commercialize robots in a wider variety of places.

Figure 10 Several humanoid robotics companies have begun pilot deployments with early customers. Source: Positive Sum analysis.

Section 4. Find Compelling Software Strategies

Our framework for the robotics frontier is that the evolution of software will drive robots from their current applications in structured environments to new applications in open, unpredictable places. What makes robots exciting today is just how little value has been captured in these markets, yet how transformative robots would be if they reached their full potential.

As robots gain market share in areas where they already have a foothold today—like in manufacturing, warehouses, or autonomous driving—they open up opportunities worth hundreds of billions of dollars. Beyond this, similarly vast opportunities exist in markets where robots have barely made inroads: working in homes and other populated places. Altogether, these current and frontier opportunities represent over $1tn. As robotic technology matures in these markets, it won’t just generate massive economic value—it will fundamentally reshape industries and redefine the technology that inhabits our homes and everyday lives.

Investors should be clear on why these opportunities have remained untapped for so long. We conclude that software is the key bottleneck preventing robots from delivering real value in existing markets, and breaking into open worlds. Robots require open-world reasoning to navigate variable environments and respond to dynamic situations. This breakthrough in software, not hardware, is what constrains the robotics frontier.

To a great extent, the hardware for frontier robotics already exists, and it’s getting cheaper. The first humanoid research robot for the home, the wheel-based Willow Garage PR2, cost $400k and required $5k of sensors to operate. But within five years of its development, the cost of similar mobile robots with arms fell 10x to less than $40k. And today, some humanoids like Tesla’s Optimus are projected to cost even less, despite the added complexity of legs. Beyond humanoids, we have the hardware for a variety of robots to grasp objects and navigate spaces. If hardware had been the only bottleneck, it’s probable that hospital delivery robots like the HelpMate—first introduced in 1991—would be in every US hospital already. Neither the fundamental design nor business model of hospital delivery robots has changed much in 30 years, but commercializing them has remained a challenge.

In contrast, the software for frontier robotics does not exist today. Current approaches to AI in robotics fall short of physical intelligence—the ability to understand variations in the physical world and adapt to a variety of physical tasks. But better open-world software for generalized reasoning could enable robots to operate in new environments and capture huge value in untapped markets.

These advances in software are what will ultimately break the commercialization barrier. Today, most robotics startups face a critical challenge: they can get their robots out of the lab and into early-stage pilots, but the software isn’t strong enough to scale them beyond that. Only two types of robotics businesses—those making industrial arms for manufacturing and robot vacuums—have successfully broken through this barrier.

Our conclusion is that investors in robotics should focus on software. This doesn’t necessarily mean only focusing on software companies; rather, investors should look for robotics businesses with a compelling software strategy. We think there are three such approaches that could yield investable opportunities. First, investors looking to make visionary bets on the robotics frontier should seek out companies looking to crack the robotics data problem in open worlds. These companies are the ones developing next-generation AI models for robots, the infrastructure to train and support them, or generalist robots themselves. Investors looking to make more near-term bets should focus on how software pushes boundaries in structured worlds where robots have some traction today—like warehouses. In these markets, incremental software advancements can lead to ROI more quickly. Lastly, investors might consider companies that sidestep software limitations entirely by developing tele-operated (remote controlled) robots designed to rely on human operators.

Three robotics software strategies

1. Crack the robotics data problem

A cohort of companies are currently aiming to build AI models for physical intelligence, and the infrastructure to develop them. This software layer could become a keystone enabling technology for robots to enter into new markets and take on more flexible tasks in existing ones.

Physical Intelligence. Founded in 2024 by a team of researchers to build robotics foundation models.

Skild AI. Founded in 2023 by two CMU professors to build robotics AI models that can jump between different robot form factors.

Google DeepMind. Working extensively on AI for robots. Most notably, it runs the Open X-Embodiment Project to consolidate real-world robotics data.

NVIDIA Isaac. A robotics development platform product designed to provide everything needed to build and refine robot software in simulation.

2. Push the boundaries of structured world robots

Companies building robots for structured environments can operate where the growing pains of robots’ limited adaptability are the least felt. This space can hold investable opportunities today because these applications will be among the first to turn incremental AI improvements for robots into ROI.

Mytra. Mytra’s material flow system uses a 3D grid and a fleet of robots that carry pallets in any direction, enabling flexible and data-rich material handling.

Robust.AI. Robust.AI’s warehouse robots use touch-sensitive handles and a human-in-the-loop UI to enable flexible autonomy and sophisticated collaboration with people.

Diligent Robotics. Diligent Robotics makes the Moxi hospital courier robot. Moxi is designed to be polite and predictable in crowded hallways and elevators.

3. Forego autonomy

Companies can sidestep some of the challenges of scaling robots by developing a value proposition that’s not dependent on autonomy. This approach may hold investable opportunities because companies can design a GTM strategy that doesn’t buckle under software limitations. Many robotics applications rely on teleoperated robots in cases where customers don’t expect automation. For example, drones and other reconnaissance robots can be teleoperated in defense or search and rescue applications. Surgical robots, like Intuitive Surgical’s da Vinci surgical system, are operated by surgeons. Teleoperated robotics companies in big, regulated markets like healthcare and defense can differentiate themselves without requiring a moat based on data or novel AI.

Intuitive Surgical. Develops robotic systems for assisting in minimally invasive surgery. It has installed nearly 10k robots in hospitals worldwide.

Teledyne FLIR. Makes a variety of reconnaissance technology for defense and industrial applications. It currently sells the PackBot (originally developed by Roomba-maker iRobot), a small tank-like rugged reconnaissance robot.

Good questions to ask robotics companies, and good answers to look for

What is your software approach for atypical events or flexible tasks?

For most robotics companies outside of manufacturing, commercializing robots hinges on enabling them to be flexible in real-world situations. There are many potential strategies to address this challenge. Robotics companies can focus on highly structured environments where robots’ required adaptability is low, design systems for humans to intervene easily when robots fail, or build teleoperated robots meant to be controlled by people.

What do you hope to learn from pilot testing?

Pilot testing robots is a key part of product development. Through pilots, robotics companies learn about how their robot operates in realistic situations and gather data about real-world corner cases. Companies should pick intentional design partners and pay close attention to unanticipated aspects of their robots’ performance and user experience.

How did you choose your price point?

To be accepted by users long term, a robot should deliver (or over-deliver) on the expectations inspired by its price point. For example, expensive home robots must not disappoint consumers, especially as they are a splurge purchase for most households. In enterprise robotics, customers like warehouses and hospitals must also evaluate opex savings against the risk of installing new systems. So robotics companies should keep price in mind from the very earliest stages of design.

Why is a robot uniquely appropriate to solve the problem you’re working on?

Hammers looking for nails are abundant in robotics. Companies should have a strong reason why a robot is the right solution to the problem they care about, compared to non-robotic alternatives.

Terran Mott is a research analyst at Positive Sum.

Pathfinder: Blake HallClick here to subscribe to print for your office or home.

Each issue, we showcase someone doing the thing they seemed destined to do. We call these people Pathfinders because, beyond the direct impact of their creations, they set an example by identifying their life’s work—and relentlessly pursuing it.

Blake Hall’s path to founding ID.me began with his experience commanding an elite platoon of scouts and snipers in Iraq. When he returned home, he discovered a problem: veterans suffered from identity theft at nearly twice the rate of other Americans, while simultaneously struggling to prove their service status to access hard-earned benefits. Since its founding in 2010, ID.me has grown into America’s largest digital identity network, with over 140 million members, as it pursues a bold vision: a single secure login for everyone’s online identity.

Colossus Review: You were 23 when you were deployed to Iraq, in charge of 32 scouts and snipers in your platoon. How do you reflect on the experience of that responsibility at such a young age?

Blake Hall: Carrying the lives of 32 people, and the hopes of their families, is an overwhelming responsibility. It’s like looking down at the ground from a great height—the enormity of what’s at stake can incapacitate you if you confront the reality of the situation directly. To do my job, I needed to let go of the scenario I feared the most, losing my men, to focus on the tasks that would reduce risk for my team.

There’s a paradox that you often have to let go of what you want the most in order to get it. In reality, I had to push what I wanted so deep down into my subconscious that it didn’t impact my performance. That mindset allowed me to influence the variables I controlled, while admitting I had no control over the external variables that might not go my way. I knew that if one of my men died under my command, I would only be able to live with myself if I had done everything I could to be the best leader for them.

I’m so grateful that each of them came home to their families. After we got back, on the last night I led the platoon, two of my snipers pulled me aside. What they told me about how the platoon felt about me made me cry. I’m so glad that I didn’t let them down.

You’ve said that “the whole point of leadership is to be inversely correlated with context.” Can you explain what you mean by that, and how to do it?

Most humans don’t like to work. On a day-to-day basis, most prefer what’s easy over what’s hard. But if you ask someone to look back on their life, many wish they’d lived a life that made a difference, versus an easy life.

Leaders help teams believe in a mission that unfolds over a long period of time. By helping the team understand what their current work means for their future self and for others, they can shape the team’s perspective to care more about the totality of their life than about their current pain and suffering. To me, this is strategic leadership. Strategic leaders wake people up to their true potential. They animate the world.

By helping the team understand what their current work means for their future self and for others, they can shape the team’s perspective to care more about the totality of their life than about their current pain and suffering.

–Blake Hall

Along the way, there are ebbs and flows as the organization and teams fare better or worse over time. When things go well, recruiting and fundraising are easy, but teams get complacent and distracted. When things aren’t going well, some people lose faith and leave, so recruiting and fundraising get harder.

Operational leaders are like gyroscopes. They acknowledge the context, communicate the big ideas, and orient the team to a better way of working together. When we were in combat and got the briefing about ‘God mode’, the risk-taking psychological state soldiers enter around month six of combat, my immediate thought was, “All gas, no brakes. Not good. Someone had better put on the brakes.” That someone is the leader.

Hall with his sniper teams in the Green Zone in Baghdad, Iraq.

The military is renowned for building effective leaders. Where does the corporate world tend to go wrong?

The military has a positive selection bias because it attracts people willing to give their life for others. For that reason, any organization with a worthy mission, based on service and purpose, will have the advantage of attracting good and capable people to it.

The military does an exceptional job training leaders and establishing core competence in domains. Now, training isn’t always an efficient use of time in the military. However, the amount of time invested to train leaders stands out from corporate America.

At the same time, our peacetime military suffers from many of the same issues that plague corporations. The best politicians, not the most skilled generals, tend to accrue power when times are soft. I think the same is true for many large organizations.

When times are hard, the most skilled generals, like General Petraeus, rise to the top out of necessity. There are lessons in that for corporate America. If you can ensure your most skilled leaders are in charge at all times, you will produce outsized value.

You said war “infused lightning in your bones”. Can you talk about how the experience shaped your sense of purpose in life when you finished your 15-month mission in Iraq?

I am definitely an addict. Adrenaline is a powerful drug. Every mission brought a different kind of high. But I knew if I kept playing that game in combat, eventually I would die.

The great gift combat gave me was to show me that life is short. The real risk isn’t founding a company with an ambitious mission that will likely fail; it’s ending up as a cog in the machinery of a huge bureaucracy, and getting stuck there.

I thought a lot about my friends who gave their lives for America. They didn’t have the opportunity to go for it. I wanted to make my life count for them.

You can’t take anything with you when you die. You can only make a positive impact on the lives of other people. That’s what will endure. And I think that happiness comes from helping others. So, that’s what I’m doing with every fiber of my being.

When did it become obvious that you could, and would, devote the next phase of your life to the idea behind ID.me?

When does a grain of sand become a pile? It’s like the sorites paradox—I knew I had something burning inside me by the second year of business school, after I got home from combat. I didn’t know it was ID.me specifically until late 2012. But I knew I would make a positive change in the world, or spend my life trying to effect that change.

What are the most effective ways to instill a sense of mission across a large number of people in a corporate setting? How do you do it at ID.me?

Humans connect with stories, not numbers. The most impactful way to reinforce the mission is to share stories of us living it. It’s about celebrating our teammates who have lived our cultural values to help a specific customer or person.

How do you measure success in life?

I measure success in business by coming through for people who have trusted me.

The best phone call I ever made as CEO was to our first VP of Product. We hadn’t talked in a few years when I called him in 2021 to tell him about our Series C, and that we’d become a unicorn. He was driving home at the time, having been to see a financial counselor with his wife, to discuss how they would pay for their triplets to go to college.

I told him he would be just fine because there was a secondary offer tied to the Series C and he was a multimillionaire. He took a deep breath, paused, and then asked me for a few seconds to pull the minivan over to the side of the road so he could cry.

In my personal life, I want my children to want to come home when they’re older, to know that my wife and I love them unconditionally, to know right from wrong, and to be brave enough to chase their dreams.

You’re allowed to invite four people (dead or alive) to dinner at your house. Who’s coming and why?