Click here to subscribe to print for your office or home.

Even after agreeing to break his silence after 25 years, Joe Liemandt is still reluctant to talk about himself. It’s hard to get him to relive Trilogy, the enterprise software company he founded in 1989, which by age 27 put him on the cover of Forbes, twice, as America’s youngest self-made centimillionaire. He isn’t keen to expound on SalesBuilder, Trilogy’s flagship expert system from the 1990s and the world’s first billion-dollar artificial intelligence product in all but name. Ditto ESW, the investment arm of Trilogy that’s acquired hundreds of software companies since 2000 and helped make him a decabillionaire, yet the mention of which makes the otherwise inexhaustible Liemandt, who always seems to be straining at some invisible leash, seem drowsy and bored.

Nor is he interested in dwelling on his reputation as a tech pioneer in everything from expert systems to manufacturing configuration, college recruitment, corporate boot camps, “tech bro culture,” remote work, monitoring workers with surveillance software, and replacing American employees with overseas contractors. Whether his reticence can be ascribed to an inhibition about the things that made him rich, or because he’s refreshingly averse to gilding them with hypocritical virtue-signaling, or because he simply doesn’t give a shit anymore, is hard to tell.

The one thing Liemandt will talk about for hours on end is Alpha School: the teacherless, homeworkless, K-12 private school in Austin, Texas, where students have been testing in the top 0.1% nationally by self-directing coursework with AI tutoring apps for two hours a day. Alpha students are incentivized to complete coursework to “mastery-level” (i.e., scoring over 90%) in only two hours via a mix of various material and immaterial rewards, including the right to spend the other four hours of the school day in “workshops,” learning things like how to run an Airbnb or food truck, manage a brokerage account or Broadway production, or build a business or drone.

Since the explosive debut of Generative AI in 2022, Liemandt has taken $1 billion out of Trilogy/ESW in order to fund and incubate proprietary AI software products at Alpha School, where he has also served quietly as “product guy,” dean of parents, and principal. After collecting a three-year data stream in these roles, while also working in a nearby stealth lab, Liemandt believes he now has “the single best product I’ve ever built, in four decades, by far.” The product is called Timeback, and its purpose, in essence, is to scale Alpha School’s concepts and results—learn 2x in 2 hours, test in the 99th percentile, and then give students the rest of their childhood back—to a billion kids.

“If you talk to anybody on the planet who knows me, they’re thinking, ‘Joe’s doing education? What happened?’” said Liemandt, who seemed surprised himself, not least to be talking to a journalist for the first time in a quarter-century. “It’s just one of those things. If you took 100 people and asked, ‘Who’s the least likely to do this?’ it would be freaking me.”

Implausible as it may seem to Liemandt, still less likely is the story of how it began, which hinges on what Alfred Hitchcock referred to as a MacGuffin: the random object or event that sets a larger plot in motion. In the case of Liemandt’s journey to Alpha School, the MacGuffin was a letter written 40 years earlier to a judge in Minot, North Dakota by a nine-year-old girl named MacKenzie Larson, who’d been taken from her home.

On her father’s wheat, corn, and cattle farm outside Minot, MacKenzie Larson loved riding horses. There were several on the farm, but her favorite was Flare, an American Quarter Horse. There was plenty else to love about the gritty tomboy farmlife, like riding motorbikes, or driving the pickup truck standing up to the neighbor’s farm, which she did while Mr. Larson worked. But riding Flare was MacKenzie’s happy place, which as time went on was a diversion she couldn’t stand to lose.

Her parents divorced not long after she was born, and her devoted mother lived in town, where she made ends meet by waitressing, selling beef jerky, and working in a clothing store. The farm belonged to Mr. Larson, who had gone to Stanford in the 1960s, but moved back home after college to take over the farm from his father, a decision he’d come to regret. Mr. Larson was a sweet and jovial man who took a loose view of parenting, and on his days of the week, MacKenzie and her older brother Caesar were left alone with a CB radio, starting when she was three. Every evening when their father returned from work, he gave them frozen pizza and ice cream, childhood staples MacKenzie tired of too young.

Still there was Flare, which she rode every day to the little school she attended in the country. She didn’t love school, but she was a good student, mainly because the local Taco John’s gave a free taco burger to any kid with straight As on their report card. It was Taco John’s that perhaps gave MacKenzie her first glimpse of what would later become an obsession with the value of incentives in school.

Things took a turn when Mr. Larson went bankrupt and had to give up his livelihood as a self-employed farmer. He still owned the farm but went to look for work in Minot where he and MacKenzie’s mother avoided each other while they fought a painful and protracted custody battle. He also remarried, to a nurse and mother of three named Angie.

Angie was a brutal personality, and her own kids from a previous marriage were always dirty and badly behaved. “Trashy” was the word on everyone’s lips in Minot when it came to those children and their mother, whom the Larson kids spent a lot of time explaining to their friends they weren’t actually related to.

Then one day in August 1985, a few days before she was meant to start fourth grade, MacKenzie and Caesar were staying with their mother in town when they received a call from their father. “We’re gonna go out horseback riding for the day,” he told them. MacKenzie usually preferred to stay with her mother, but if riding was involved, she was in. She put on her riding clothes, her cowboy boots, her jeans, her shirt, and got ready for a day with Flare. When Mr. Larson arrived outside in the car, they hopped in, and the car peeled away from town.

“You missed the turn!” MacKenzie yelled from the backseat when he didn’t turn right at the country road that led to the farm.

“We have a change of plans,” he responded.

“But I want to go ride first,” MacKenzie said.

“No,” said Mr. Larson. “We’re moving to Nebraska. I’m taking you there now.”

Caesar, who was 13, and perhaps understood more immediately than his nine-year-old sister what was happening, insisted on stopping at a payphone to call their mother. “You at least have to let us tell her,” he said. But Mr. Larson wouldn’t stop, not until they crossed the state line into South Dakota, where they stayed overnight in a motel during the 600-mile drive to Columbus, Nebraska. It was at the motel in South Dakota that MacKenzie realized she never got to say goodbye to Flare and might not see her again, which she never did.

Angie and her kids had gone ahead and were already at the house in Nebraska when MacKenzie, Caesar, and their father arrived. The Larson kids had packed nothing and their father had brought nothing for them. The next day would be MacKenzie’s first day at her new school in Columbus, but she’d been wearing the same outfit for two days already. When she demanded a change of clothes, Angie went out to the store and came back with a pair of bib overalls.

“Here, put these on,” Angie told her.

“I need a shirt to put on underneath,” MacKenzie said. “I don’t have a shirt.”

“I don’t care,” said Angie. “Put these on and get out of the house so I can unpack.”

When all the neighborhood kids came around to get a peek at the new family that had moved to town, their first sight of MacKenzie was of a girl wearing bib overalls with no shirt on, and it stuck. MacKenzie had always been popular at the country school outside Minot, but now she was the girl who didn’t have a shirt, and there was no coming back from it. The only kids who would speak to her were two other ostracized girls, both of whom were indeed a little off. She is one of us, they understood, when they saw the girl with no shirt on her back.

It was Taco John’s that perhaps gave MacKenzie her first glimpse of what would later become an obsession with the value of incentives in school.

Her parents’ custody battle intensified as a result of the forced move to Nebraska, which MacKenzie’s mother fought relentlessly in court. She visited her children whenever she could, but otherwise couldn’t see them, as Mr. Larson wouldn’t let them leave Columbus. The one exception was when MacKenzie and Caesar were required to take the stand in Minot, where they were questioned by a child psychologist and family court judge, who ultimately decided to deny their mother full custody. Such was the mental and emotional atmosphere of the girl with no shirt during her first semester of fourth grade, where the teacher made things worse.

Other than riding horses, MacKenzie’s favorite thing to do was draw, which she was also good at. In Minot, one of her drawings had won first place in a state fair competition, and she’d also won the coloring contest at a local grocery store. In her fourth grade classroom in Columbus, the teacher held a drawing contest for the students and put all the drawings up on the wall where she would pick a winner. MacKenzie’s drawing was of Flare, and was clearly the best. When the teacher announced the winner, she held up some pathetic thing doodled by a snot-nosed classmate.

“How’d MacKenzie’s not win?” some other kids piped up. It was clear even to her tormenters that hers was best. “How’d mine not win?” MacKenzie asked the teacher. “Mine was the best.”

“You obviously cheated,” the teacher said. “You traced it, or you had an adult do it for you. It’s too good.”

“I will sit down and draw you a new horse right here,” MacKenzie objected, “you can watch me do it.” But the teacher wouldn’t budge, which the other kids knew was unjust, but which they also found funny, because it was happening to the girl with no shirt. It was, perhaps, the first time MacKenzie imagined what would also become a future obsession: freedom from a life stuck in a classroom, playing rigged games, at the mercy of a bad teacher.

It was also, happily, the only semester she would spend in Columbus. At the end of 1985, they moved from Columbus to Lincoln, where MacKenzie had at least one shirt now, and could reestablish herself at a new school.

In the spring of 1986, Caesar called a friend in Minot and obtained the address of the courthouse. He and MacKenzie wrote a letter about how the court had made the wrong call, detailed their situation in Columbus, pleaded for a reversal of the judge’s decision, and mailed it to the courthouse.

A few weeks later, MacKenzie and Caesar returned home from school one day to find Mr. Larson and Angie wouldn’t speak to them. The adults didn’t know exactly what the Larson kids had done, but they knew they must have done something, because the court in Minot had just called: The judge reversed his decision and granted their mother full custody.

On the last day of the semester, their mother and her fiancé, soon to be their stepdad, picked them up from Lincoln in a motorhome and moved them to Denver, Colorado. The new stepdad was a keeper, and had some money from his businesses in real estate and hog barns. On a ranch he had outside Denver, he got MacKenzie a new horse.

MacKenzie’s father and Angie eventually divorced, and Angie was later convicted of murder; she’d stolen morphine from a patient and swapped it out with saline, which resulted in the patient’s death. The nature of Mr. Larson and Angie’s demise was nothing to take pleasure in. But it underscored how much the odds had seemed stacked against MacKenzie when she was only nine, and how much thereafter, things turned around. She never came to like school, but in Denver she was a good student, and popular again. She had the best mom a kid could ask for, and a fantastic stepdad. And she had a horse.

In a word, she’d been given her childhood back.

In high school, during her summers and other school breaks, MacKenzie worked from 6am to 4pm at her stepdad’s hog barns in Nebraska and Minnesota, where she castrated pigs, clipped their nails, and processed them. She also cleaned houses, worked on her grandparents’ farm in North Dakota, and did other manual labor that her mother had her do, not least because MacKenzie should know how to work with her hands and interact with people from all walks of life—another focus of her future attention.

One day at the hog barn in Nebraska, MacKenzie went to the lunchroom during her break, and up walked a rough-looking girl with a mullet and, naturally enough, a tattoo on her arm of a naked woman riding a motorcycle above a ribbon emblazoned with the words “Bad Bitch.”

“What happened to you, Barbie?” the Bad Bitch said to MacKenzie. “Ken fuck your best friend?”

“Huh?” said MacKenzie.

“Steer clear of that gal,” another coworker told her.

It was at the hog barn later that summer that MacKenzie got a call from her mother, telling her an envelope had arrived in the mail from Stanford University, her father’s alma mater. The envelope was big and thick, she said. MacKenzie knew what it meant, hung up the phone, and went back to work. She was working that day with an electrician, who asked why she was crying. She’d just gotten some good news, she told him. She got into the college she wanted.

“What college?” he asked.

“Stanford.”

“What’s that?”

“It’s in California.”

“What in the hell do you want to go there for?”

“It’s a good school.”

“What are you gonna study there?”

“I don’t know,” said MacKenzie. “Maybe economics or psychology.”

“What in the hell would you do with that?” the electrician asked.

Word got around that MacKenzie got into a good college in California, and would be leaving the hog barn at the end of the summer. On her last day, as she said goodbye to her coworkers, the Bad Bitch approached her again.

“I don’t want to see you here again,” she told MacKenzie. “Go do big things now, you know, in this world.”

MacKenzie and Flare, 1985

All MacKenzie knew when she got to Stanford was that she wanted to host the Today show. She didn’t know you could study broadcast journalism or communications, so she studied econ and psychology. She also took an introductory engineering course, since that was the sexy major at Stanford. Despite working her tail off and eating up all the professor’s office hours, she sucked at it—it might as well have all been Cantonese. She earned an F but wound up with a C+. Knowing there was no chance she deserved it, she asked the professor why.

“I’m not going to penalize you for trying something and working hard at it,” he told her. “But if I ever see you in the engineering building again, I won’t be so kind.” It was, perhaps, the first time MacKenzie imagined school as a place where you could try and fail at anything, and not get whacked for it.

MacKenzie was a fuzzy (Stanford’s colloquial term for non-STEM students), which meant the paths leading out of her senior year, as she saw it, were investment banking and management consulting. She did a summer stint at an investment bank in San Francisco and hated it. She was the daughter and granddaughter of farmers, self-employed entrepreneurs with control over their own time and no boss to obey, other than the weather and crops. (By Thanksgiving of her freshman year, Mr. Larson had repaired his relationship with MacKenzie and even her mother, and wound up, as he is today, close to both.) She also knew she wanted to have a family one day. MacKenzie had a life to live, in other words, and didn’t want to spend it working 100 hours a week at something she didn’t love.

So in 1998, she returned to Stanford for a recruiting event. The event was put on by a company called Trilogy, which did something or other to do with enterprise software out of Austin, Texas. “I’m a fuzzy, not a techie,” she told the Trilogy recruiter. “We’re looking for people in marketing and business development,” the recruiter responded, and made her an offer, which she accepted, and moved to Austin.

On her first day in the company’s legendary training program, Trilogy University, MacKenzie was assigned to a supervisor, the CFO Andy Price, a techie who’d been working at the company since he was 16. Trilogy was full of dropouts, an ethos established by the founder and CEO, who dropped out of Stanford in 1989 to start the company. By 1996, Forbes had put him on the cover twice in four months. By 1998, Trilogy was doing $150 million a year in revenue and was valued at about $1 billion, thanks in large part to SalesBuilder, a landmark artificial intelligence system. Forbes, Rolling Stone, and The Wall Street Journal couldn’t get enough of the founder, Trilogy’s unique culture, its association with something real called “AI,” and its high-octane strategy for recruiting and training new employees. At the time, Steve Ballmer remarked that Microsoft was losing more recruits to Trilogy than to any other company.

When MacKenzie started there that year, it wasn’t yet clear that Trilogy would survive the dot-com bust by acquiring hundreds of dying software companies, making them ruthlessly efficient, and generating cashflow that would eventually make the founder a billionaire several times over. Nor was it clear that by 2004, MacKenzie would marry Andy Price. It certainly wasn’t clear that Trilogy’s young founder, who’d spent much of the previous decade as a darling of the tech and business press, would soon step out of the limelight, seal himself off from public attention for the next 25 years, and quietly begin taking $1 billion out of Trilogy’s cashflow machine in order to fund a stealth project that would perplex everyone who ever knew him.

“I actually do remember the first time I met Joe,” MacKenzie told me in June, as we sat in her downtown Austin apartment a few blocks away from Alpha School—which she founded in 2014. In the hallway leading out from the Prices’ dining room, a massive painting of galloping horses hangs on the wall.

“It was while I was in Trilogy University. I was on a computer, and he walked up behind me and asked what I was doing. I told him I had a toothache and was trying to find a dentist in Austin.”

“Oh,” Liemandt told her. “I’ll send you to mine.”

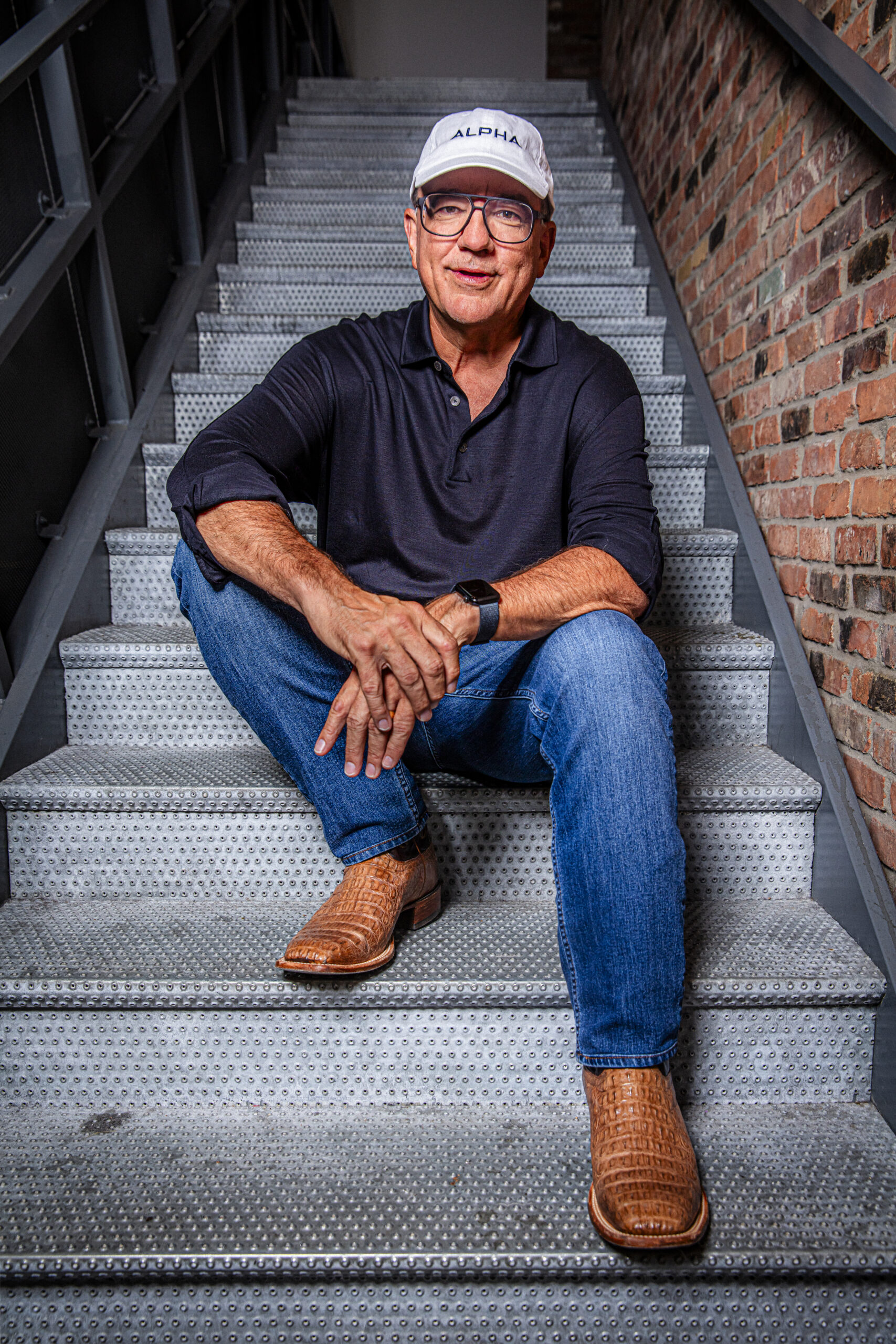

Liemandt and Price at Alpha School in Austin, Texas (July 2025)

Joe Liemandt was also good at school, and also hated it.

As a kid, he moved every couple years, including from Minnesota to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where his father Gregory was Jack Welch’s head of planning at General Electric’s components and materials group; to Washington, DC, where Gregory ran GE’s Information Services; and to Dallas, where he ran a maker of software for mainframe computers. Liemandt’s mother was a devout Catholic and sent him to parochial schools, which he was adept at gaming. He would calculate how many days he could skip and get suspended without getting expelled, for example, and figure out how to score exactly 89.5% in each class, reckoning it would be rounded up to 90%, which was as good of an A as 100%. On certain tests, confident he’d scored 100% on 90% of the questions, he’d turn it in without answering the other 10%. In his free time, he preferred to read his own books, and the business plans his father brought home from work.

The term “artificial intelligence” had been coined at Dartmouth in 1956, leading to the first AI spring that quickly ended in the first AI winter. In the 1970s, when Liemandt was growing up, the second boomlet began. The innovation that proliferated back then was called “expert systems,” a computer system that could emulate the decision-making ability of a human expert by reasoning through bodies of knowledge, represented as “if/then” rules (e.g., if the temperature drops below 62 degrees, then the heater turns on), rather than procedural programming code (more like a step-by-step list of instructions). In high school in the mid-80s, Liemandt wrote a paper on neural nets—which were accurately seen at the time as being decades away, given the limitations in computing power—and read all the articles he could find on expert systems, vision processing, voice recognition, and other burgeoning categories in the field of AI.

Liemandt defied his parents’ wishes to attend Georgetown, a Jesuit school, and enrolled at Stanford, knowing he wanted to start a software company and build a product that “Jack Welch would buy.” He majored in econ because he found it easy, but also took classes in computer programming, including with Ed Feigenbaum, the father of expert systems and ontologies (also known as “object models,” representations of a system’s components and the relationships between them, which could theoretically expand the reasoning capabilities of expert systems).

As much as Liemandt took to Feigenbaum, and the appealing idea of flat expert systems incorporated with three-dimensional object models (I’m not just dropping words I learned a few weeks ago here; I have a point), the technology itself was still incredibly brittle and expensive to build, and seemed like a potentially bad area to go into, as evidenced by doomed companies like IntelliCorp and Symbolics. Liemandt also chafed at the whole academic part of being a student, preferring to spend hours in the computer science library reading research papers and articles about famous software companies. Stanford still had its perks, though. Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Scott McNealy, and Bill Joy were some of the figures who came through Liemandt’s classes and offered students jobs after graduation. During his freshman year, he started a consulting firm to help companies in Palo Alto with their IBM PCs and new Macintosh computers.

In the course of his part-time consulting work, Liemandt noticed that when he ordered equipment, it usually arrived late, or with missing parts, or—most irritating of all—with parts incompatible with his clients’ computers. True to form, he went back to the CS library and started researching the excruciatingly dull problem of “configuration.”

You’ve likely encountered a configurator (I swear this is going somewhere) when buying a car: I choose the hatchback, in Ingot Silver, with the base trim, and a hybrid engine, with foldable rear seats, and all-wheel drive, at something like the price the company’s website or dealership told me I could have a hatchback for. This isn’t such a problem anymore, but back in the 80s, companies routinely sold product combinations that were either physically impossible to manufacture or that they couldn’t deliver in working condition even when they were. Your average sales rep at Chrysler, say, was just out there selling orders for a puce LeBaron with 11 seats and a V12 engine at the price of a Plymouth Horizon, if that’s what the customer asked for.

The stakes were low, albeit infuriating, when it came to buying a car or a new Dell computer. But configuration—on both the sales and manufacturing sides—was just as big of a problem for companies like AT&T and Boeing, whose phone switches (which could theoretically make the number “9-1-1” stop working) and airplanes (which can theoretically fall out of the sky) had billions of potential combinations. “The problem is things get really combinatorial as things get complex, and they go combinatoric,” is an actual sentence I heard Liemandt say with my own ears.

Sometimes the engineer checking the order on the manufacturing floor would tell the sales rep to tell the customer that the company just sold them something that won’t work. But oftentimes, the misconfiguration wouldn’t be caught until midway through the manufacturing process, costing a given company tens or hundreds of millions of dollars. At that point, the company could either sink millions more into fixing it, or else it could bashfully ship the customer the hunk of metal, glue, and mangled circuits they ordered for free to keep as a memento, preferably in a museum where it wouldn’t kill anyone who tried to use it.

From his nook in the Stanford CS library, Liemandt figured out that the typical US manufacturing company in 1987 was spending 40% of its noncapital budget on sales and marketing, which unlike administrative and R&D costs, still hadn’t been automated. He calculated that the computerization of the sales process, which had no good products in existence, was a potential $10 billion market.

He also learned that a company called Digital Equipment Corp. was trying to use expert systems to computerize its own sales configurator, and that Hewlett-Packard, IBM, and Bell Labs were trying something similar, and that everyone was stuck. Making a piece of software powerful enough to catalog the massive inventory of a company like IBM; smart enough to continually reconfigure the company’s offerings as products and prices changed; and easy enough for an ordinary sales rep to use, was just a really hard thing to do—too hard even for the big 16-cylinder brains at a place like Bell Labs.

So Liemandt decided to break his mother’s heart, and arouse his father’s fury, by dropping out of Stanford in the first quarter of his senior year, in order to found a startup called Trilogy, which would figure it out.

“You’re a moron,” Gregory told him.

Liemandt was joined by John Lynch, a superior programmer and software developer, who dropped out of Stanford with him, and Christina Jones, Chris Porch, and Seth Stratton, three other co-founders who stayed in school until they graduated. With their access to student housing stripped, Liemandt and Lynch offered some friends off campus $50 a month to rent their garage, where the Trilogy kids began coding day and night with the assistance of Jolt Cola and beer.

Jobs, Gates, and Dell had done it, but back in 1988, dropping out of college to build a startup in a garage was not yet fully consecrated as the herd ritual of tech billionaires. Liemandt and Lynch’s brash decision was therefore not enough to wow any venture capital firms on Sand Hill Road, who were also unimpressed by their pitch for an enterprise software company with no experienced management or technical teams, promising to build, within one year, the kind of configurator Bell Labs had been failing to produce for the previous five, and then sell it to Fortune 500 companies for millions of dollars. For one thing, the golden rule of venture capital was that Fortune 500 companies didn’t buy enterprise software from startups.

To fund Trilogy, Liemandt sold the Microsoft stock he’d bought at the company’s IPO a couple years earlier using the money he’d earned doing computer consulting. Otherwise, his mother remembered, “Outside of me slipping him $100 bills in the airport so he would eat, there was no [family] seed money.” This quickly became a problem.

The Trilogy team was in the process of figuring out how to create a system simple enough for your average sales rep to use, and also easy enough for programmers to update without the whole thing crashing. In a nutshell, their idea was to combine everything they’d learned in Feigenbaum’s classes: constraint-based equations (math that defines restrictions on the possible variables within a system) with “if/then” rule-based programming and three-dimensional object models. And it actually seemed to be working! But only very slowly, as each improvement in one part of the system would create a new problem in another. Liemandt was continually convinced the configurator was only three more months away, but it began to dawn even on him that the timeline he’d been promising was, to put it mildly, insane.

Thankfully, 1990 was a year of explosive innovation. It was the dawn of the World Wide Web, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the Human Genome Project, for example. But for Trilogy, the year’s crowning technological breakthrough was something far more sublime: the pre-approved credit card mailer.

Once something you had to apply for at your bank, by 1990 credit cards just appeared in your mailbox in an envelope with the words, “You’re Pre-Approved!” Credit scoring wasn’t too sophisticated yet, so Liemandt and his team applied for stacks of them. One would come in with a $5,000 limit, they’d take $4,000 as a cash advance, then get another one to cover the monthly payment on the other. Each new credit card form asked how many other credit cards you already had and provided a little box with enough space for a single digit. Liemandt had about 50, which he pyramided to keep funding Trilogy—still convinced that the configurator was only three more months away.

Yet by the fall of 1991, they’d been three months away for two years. While they worked 20-hour days and slept under their desks, their former classmates at Stanford had gone on to work for Steve Jobs and Bill Gates. Some of the other Trilogy founders’ parents started calling Liemandt asking him to let their children off the hook. His own friends began politely suggesting that he might not know what the hell he was doing. At one point, Lynch announced he was moving from Palo Alto to Austin, Texas, figuring he might as well live somewhere cheaper while they approached half-a-million dollars in credit card debt. Liemandt decided the rest of the team would follow Lynch to Austin, in part because his father, who lived in Dallas, was diagnosed with terminal cancer.

Then came their first break. The hot up-and-coming company at the time was the 3D graphics computer workstation maker Silicon Graphics Inc. (SGI), started by James Clark, the co-founder of Netscape. Betty Watson, an SGI executive, heard through the grapevine at Stanford that former Feigenbaum students had dropped out to build a configurator. She called Liemandt and told him they needed one. That’s great, Liemandt told her, but we’re about three months away. Ok, Watson said, keep us posted.

Two weeks later, on a Friday, she called him again to ask if it was ready yet. No, Liemandt told her, as of that Friday it was about three more months away. “Look,” she told him. “We have an executive committee meeting Monday because we had a big configuration error and it’s cost the company millions of dollars. We need to see it. This is your shot.”

“OK,” Liemandt said apprehensively. “As long as everyone knows it’s only a demo.”

Liemandt and his team stayed up the whole weekend coding. They piled into the company Hyundai and drove to ComputerWare (the old Mac Store) to purchase a Radius Rocket accelerator card, which made their Mac five times faster. When they entered ComputerWare, they checked to see if any of the sales reps who knew them were there that day. None were, which was good, because the Radius Rocket cost $3,000—almost a whole credit card—and they’d be returning it for a refund right after the demo.

By Monday morning, Trilogy’s configurator software was comprehensive but incredibly slow—on a good day, it could solve a very complex problem, but it would take 10 minutes. It would also crash about 60% of the time, which they sought to forestall by prestaging a particular configuration of a big SGI computer system for the sake of the demo. Of the six billion or so possible permutations, the Trilogy team knew of four that wouldn’t make it crash.

When they got to the executive committee meeting of SGI, Tom Carter, another Trilogy co-founder, set up their Mac with the power cord running into an outlet on the wall behind him, and set up his chair near the wall where he could keep his foot on the cord. The idea was that Liemandt would get up there and suggest oh, I don’t know, just spitballing here, the only SGI computer system configuration we know of that won’t make the program crash, Tom would hit go, and then Liemandt would spend 10 minutes regaling the executive committee with a detailed and confusing explanation of how their configurator worked and how they built it by dropping out of Stanford and living in a garage. All the while Tom would keep his eyes on the monitor, watching the little Mac icon spin incessantly, to see if it was about to crash. If he saw that it was, he’d step on the power cord and go “Oh no! The power cord!”, and Liemandt would say “TOM!”, and then turn to the committee to suggest that they, busy executives that they were, receive the demo another time.

Except before the demo even began, one of the executives announced that he’d been at HP during their failed configurator days and was not willing to see a demo; he wanted to put in real values. He walks up to Tom’s Mac and inputs real values and clicks go, and the Mac icon starts spinning. Liemandt looks at Watson like, Are you fucking kidding me?, and Watson looks back at him as if to say, Oh well!

So Liemandt starts sweating and gabbling about rule-based programming and constraint-based equations and three-dimensional object models and dropping out of college and living in a garage. It’s the longest 10 minutes of his life, it feels like 10 hours, he’s like Colonel Gaddafi giving a speech at the United Nations, when all of a sudden, Tom shouts:

“It worked!”

“Of course it worked!” said the quick-footed Liemandt. “It always works!”

The stupefied executive from HP walked up to the monitor to look at the answer the system generated. “Holy cow,” he said. “This is the right answer.” Liemandt let the committee know that it would cost $100,000.

“Of course it worked!” said the quick-footed Liemandt. “It always works!”

“I hate to do this, Joe,” another executive interjected, sucking the air out of the soufflé. “But I didn’t know coming into this that you were five guys in a garage. SGI is doing a billion dollars of orders. Every order would have to go through this system. We need to buy this from a real software company.” The golden rule of venture capital appeared to be true.

Deflated, Liemandt left SGI with the power cord between his legs and drove back to ComputerWare with the rest of the Trilogy team to return the Rocket Radius. When they regrouped in the garage, they had the tough conversation. SGI was the coolest, most innovative startup, and if they wouldn’t buy Trilogy’s product, no Fortune 500 company would. They walked to a bar across the street, began drinking heavily, and discussed accepting defeat: admitting failure and shutting Trilogy down.

But they were so close, Liemandt insisted. The product was only three more months away! Plus, there’s a peculiar quirk in US bankruptcy law, he pointed out. When you go bankrupt in America, it’s binary: You’re either bankrupt or you’re not. If you are, your credit rating gets destroyed for seven years, you lurch through a maze of legal documentation, creditor negotiations, asset liquidations, court hearings, and recriminations from your heartbroken mom, incensed dad, smug professors, and gloating friends. But the amount of money you’re in debt is irrelevant. Whether you’re down $500,000 or $1 million in pyramided credit cards doesn’t actually matter.

“What if SGI is just stupid?” he offered. “How about we get some more credit cards?”

Such was the bartop consensus when a few weeks later, Watson called Liemandt again to say they looked at all their other options and came up empty. Trilogy was their only choice, and SGI needed a configurator. Liemandt, quick on his feet again, calculated that the corollary to the rule that big companies don’t buy enterprise software from startups was probably that when they have no other choice, they’re price insensitive.

“Great,” he told Watson. “The price has tripled. It’s $300,000.”

“Done,” she told him.

Three months later, HP called. “It’s $3.5 million,” Liemandt said, understanding they’d abandoned their own configurator pursuit. They accepted.

Six months after the HP deal, AT&T called. Liemandt told them it cost $7.5 million. Done. Then IBM called, having abandoned its internal project, too. $25 million, Liemandt said, which would have been the biggest enterprise software deal in history to that point. IBM accepted. Then came Boeing, GE, Ford, and hundreds of others writing eight-figure checks.

Liemandt saw that big customers would only keep proliferating, and that being a bunch of kids in a garage would quickly go from being a sort-of-but-not-very charming quirk to an actual problem. At a certain point, he turned to his father for help.

Gregory Liemandt had spent the previous two years pleading with his son to go back to Stanford to graduate, worried he was an inveterate shirker who’d never stop quitting after scoring 89.5%. But now Gregory was dying, and while he wouldn’t live to see his son’s biggest successes, the early deals made it clear he was going to be alright. He told Joe that once he found the thing he clearly loved, and started working 20 hours a day and sleeping under his desk, it was clear he wasn’t a lazy little shit—he was anything but. With the time he had left, Gregory said, he’d teach his son everything he knew. Liemandt made his father chairman of Trilogy until he died in 1993, when Joe was 25.

Photo by Robert Daemmrich Photography Inc/Sygma via Getty Images

By 1994, Trilogy had finally perfected the configurator, which they called SalesBuilder, the world’s first commercially successful, industrial-scale expert-system technology, then synonymous with artificial intelligence. In 1995, Liemandt received 20 calls from investment bankers begging to take Trilogy public at a valuation of $1 billion. In June 1996, the Trilogy team was on the cover of Forbes under the headline, “They Keep Getting Younger!”; in October, Liemandt was on the cover of the Forbes 400.

After Gregory Liemandt died, his old boss Jack Welch told the younger Liemandt he’d be there for him if he ever needed help. Fresh off the Forbes 400, Liemandt flew from Austin to Connecticut to visit Welch at his home. In 1996, Joe Liemandt, age 27, estimated net worth $500 million, did not appear to be someone who needed help. On the flight over, he was feeling himself.

Then nearing the end of his 20 years at the helm of GE, Welch was a rock star in the business world, famous for his ability to motivate and inspire fierce loyalty in people, and generously reward winners. He was also known for implementing a Darwinian culture marked by interpersonal confrontation, fierce competition, and pitiless culling of underperformers.

“So you’re basically a good product manager,” Welch told Liemandt over lunch. “Is that how I should think about you?”

“I run a company with a billion-dollar product,” Liemandt said.

“By the way,” said Welch, “GE Medical doesn’t like your product.”

“It just won e-commerce product of the year,” Liemandt objected.

“I don’t care if it comes from heaven above,” Welch fired back. “If General Electric doesn’t get a return on its investment, your product sucks, your company sucks, and you suck.”

“You could be doing 10 times more, Joe,” Welch said. “Don’t be such a wuss.”

“Krug can’t say exactly what’s bugging him,” Rolling Stone reported in an October 1998 feature titled “Wooing the Geeks,” in which a reporter followed Byron Krug, a senior at Carnegie Mellon, as he weighed the increasingly elaborate pitches tech companies were making to top software engineering recruits.

“Maybe it’s the stories about Joe Liemandt, Trilogy’s charismatic 29-year-old co-founder and CEO, who drinks with the gang on Friday evenings and has been known to gather up those left at the bar at midnight and fly them out to Vegas for a weekend of Blackjack. Maybe it’s the fact that half the people who work at Trilogy look as though they’ve just wandered in from the H.O.R.D.E. tour. Maybe Krug can’t bend his mind around the fact that everything about Trilogy, from its company ski boat moored at a nearby marina to its 24-7 work ethic, shrieks a single message: Live fast or die.” (The article went on to note the prevalence of lemon drops and tequila shooters at Trilogy parties, and the femaleness of its attractive recruiters. Readers may be surprised to learn that after receiving offers from several companies, the article ends with Krug accepting Trilogy’s.)

The magnitude of the dot-com bubble in late 1998 is suggested by Rolling Stone’s decision to exhaustively chronicle the courtship of a Pennsylvania computer nerd by a sales configurator company in an issue that also featured the Wu-Tang Clan, Tom Wolfe, and “A Journey to the Heart of Marilyn Manson: Love, Drugs, and Redemption in the Hollywood Hills.” Yet it is also a cultural artifact of the Welch-sized imprint Liemandt was starting to cast on tech culture, which has since been both underestimated and skewed.

Take Liemandt’s innovations in recruiting and training. As Trilogy’s annual revenues started to exceed $100 million, its employee base was growing about 35% a year. But in the 1990s, there were not many software engineers in Austin, Texas. Rather than poach experienced engineers, managers, or business developers from companies in Silicon Valley, Liemandt started aggressively targeting promising students with no prior work history, developing close ties to every top-20 computer science department, blitzing their campuses with recruiting events, taking recruits out to fancy dinners, flying them out to Austin, and seducing them with gifts of CDs, laptops, and (in a few cases) cars. In 1998, Trilogy spent $10,000 per head on recruiting about 300 new hires.

It sounds almost quaint now, but Liemandt’s preference for latent talent, potential, and ambition rather than proven experience (based, one imagines, on his own personal trajectory) was unique in tech. “Microsoft is the most aggressive recruiter we have on campus,” said the dean of undergraduates at Carnegie Mellon at the time. “But Trilogy is the savviest.”

The same was true of Trilogy University (TU), the almost mythological 100-day, 100-hour-a-week gauntlet through which new hires passed, which later inspired similar boot camps at Google and Facebook. At TU, new hires were assigned to a section (about 20 kids), a section leader (a top Trilogy executive), and an instruction track designed to mimic real technical challenges and customer engagements at the company. Next, they were divided into smaller teams to come up with a product idea, build a prototype, create a business model, and develop a marketing plan. Liemandt would then play VC and judge whether to fund and launch each project, which he did about 15% of the time—in turn using TU as one of the company’s primary R&D engines. (Between 1995–2001, TU projects produced $25 million in revenue and formed the basis for $100 million in new business). During all 100 days, each new hire’s work was continuously monitored, measured, assessed, ranked.

Coverage of TU was unrelenting in the The Wall Street Journal, Fast Company, Forbes, and the Harvard Business Review, which crowned it the most effective corporate boot camp in history. The business and tech press likewise couldn’t get enough of Liemandt himself, who seemingly every reporter noted drove a beat-up Saturn, ate at Wendy’s, patronized Supercuts, and rented an apartment with no TV in it, despite a net worth soaring past $600 million.

Harvard Business Review largely refrained, but the press also couldn’t get enough of the more idiosyncratic aspects of the culture Liemandt, his recruiting strategy, and TU inculcated. Recruits and employees alike worked from 8am–12am, often seven days a week and almost always on holidays (“competitive advantage days”), and wore whatever they liked (also somewhat new at the time). There were also, indeed, Friday night Parties on the Patio (POP), which were sometimes followed by buses to a beach several hours away, or chartered planes to Hawaii or Las Vegas, where Liemandt would put up cash at the tables to encourage employees to place five-figure bets: If they won, they kept the winnings; if they lost, he’d deduct it from their paycheck.

Taken together, the culture Liemandt cultivated of limitless potential, grueling work ethic, meticulously measured results, hard-partying, and audacious risk-taking resulted in an intensely devoted, almost cultlike bond at Trilogy, as evidenced by the large number of people hired there in the 1990s who still work for Liemandt today. It wasn’t for everyone, but then again, the company made no secret about it, and no one was forced to work there.

In the popular 2018 book Brotopia: Breaking Up the Boys’ Club of Silicon Valley, there is a chapter called “How Trilogy Wrote The Bro Code,” which holds Liemandt partially responsible for seeding the tech industry’s later reputation for sexism: “Trilogy pioneered new recruiting strategies in the tech industry, selected a different type of computer programmer, and encouraged an insane amount of risk … all while helping to trademark the work-hard, party-harder brogrammer culture we’ve come to know, complete with Dom Pérignon, strippers, and high-stakes gambling.” The book does not allege any wrongdoing, misconduct, or unethical behavior, but does cite “peer-reviewed social science” on topics like male narcissism and high-achieving female imposter syndrome to argue that “Liemandt’s bro style—his volatile mixture of entitlement, hubris, and risk taking” created “an even chillier climate for women in technology.”

To be fair, as a former jock, I share Brotopia’s more general horror at the colossal power, wealth, and social wattage of nerds over the last 30 years, whose accession to the American aristocracy via mastery over technologies and logistics nodes now key to the operation of advanced societies I blame for basically everything that’s gone wrong since the end of the Cold War. Nevertheless, if Liemandt made a major cultural mark in the 1990s, it was not the predictable domination of a major new industry by men; it was the reclamation of various masculine-coded traits and lifestyles by male types previously coded as sissies.

Which isn’t to say that Liemandt was not responsible for more genuinely controversial innovations in tech. After the internet bubble popped, he would spearhead two.

In the wake of the dot-com crash in 2000, Trilogy retained many of its biggest customers like Ford, IBM, and AT&T, but began cutting staff and costs, and its light in the tech firmament appeared to fade. Liemandt had always owned more than half of Trilogy and never took it public, but now he bought out the other shareholders to achieve 100% control. He also got married and planned to have kids, whom he wanted to give a normal life. After a decade in the limelight, he stopped giving interviews or talking to reporters, and vanished from public attention. At one point, he fell off the Forbes 400.

While the rest would remain true for the better part of three decades, his disappearance from the list of the 400 wealthiest Americans didn’t last long.

In 2001, Liemandt started ESW Capital (named for “enterprise software”), an investment firm and separate legal entity from Trilogy but which in practice is one and the same. Liemandt’s insight that led to ESW was that some software companies are growth companies (meaning they’re focused on new prospects and customers), while others are installed-base companies (focused on retaining existing customers). “There’s a cycle in a company where it’s built to last,” he said, “and there’s a cycle in a company where it’s built to die.” (Unsolicited advice, not from Liemandt: If a company has a name like “Ensequence” or “Compressus,” it is built to die.)

In the early aughts, there were a lot of private credit guys with billions of dollars in underwater debt, and a lot of software companies that were built to die. ESW began acquiring them, collecting tax breaks on net operating losses, putting a stop to any growth plays, slashing personnel and R&D costs, installing commando Trilogy operators to make them ruthlessly efficient, focusing on delivering business value to the companies’ existing customers, and generally keeping the melting cube cold as long as possible while sucking out the cashflow.

ESW has since acquired hundreds of these companies. Unlike private equity, it doesn’t flip them but keeps them running and bundles them together in a subscription-service library, like Netflix. ESW’s offers are known for being friendly to founders and investors looking to get out, but otherwise, the day Liemandt shows interest in your company can be an unsettling one, akin to the moment an activist hedge fund shows up in your stock price.

In addition to the Trilogy team’s prowess as operators, Liemandt was able to collect dying companies and bale them into a massive cash machine by once again being among the first to identify strategies that would eventually become widespread—both having to do with his early intuition about the viability of remote work.

First, for both Trilogy and the companies ESW acquired, Liemandt began buying out, laying off, or seeking voluntary exits from US employees and replacing them with overseas contractors, meaning 1099 contracts with no bonuses or equity. For a time, Trilogy/ESW was the No. 1 US-based recruiter at the Indian Institutes of Technology, and also did a lot of hiring in Ukraine, Venezuela, and Hangzhou, China. Later on, Liemandt started Crossover, a LinkedIn account, which eventually became the world’s largest recruiter of remote full-time jobs, and puts recruits through remote tests for intelligence and competence similar to those pioneered at Trilogy University.

Second, on every contractor’s device, Liemandt implemented a system called WorkSmart, described as a “Fitbit for how you work.” The germ for WorkSmart started at Trilogy, which recorded overseas workers’ screens in order to prevent fraud. In essence, it’s a webcam tracking feature that takes screenshots every few minutes, and spyware that tracks mouse clicks and keyboard strokes, allowing Crossover to collect workflow data and track the productivity of each worker. While every Crossover contractor agrees in advance to have WorkSmart installed on their device, Liemandt’s innovation in employee monitoring and measurement, combined with his preference for a high turnover workforce of easily hirable and fireable contractors in predominately developing countries, led Forbes to accuse him in 2018 of running a “global software sweatshop.”

Such concerns would seem offset, at least to a significant degree, by the fact that Crossover sets pay “based on global value, not the local market,” in tiers of $60,000, $100,000, $200,000, and $400,000, always in US dollars. For an independent contractor in Venezuela, or for that matter in Randolph County, Georgia, concerns about tracking tools or the lack of benefits would seem more or less beside the point.

The bigger point is the way in which Liemandt’s evolution from Stanford to Trilogy to ESW and Crossover solidified his worldview: record, capture, and minutely measure all the data possible; feed it into a system which operates and compounds on logic and predictability; continually abstract people from the system; precisely define what should and shouldn’t be done by the people that remain; promote and pay the overachievers well; and cut or replace the rest.

It’s a worldview that is many things. It’s one that Jack Welch would approve of. It’s one with a conspicuous absence of any spiritual element. It’s one that requires deep disagreeableness, indifference to social mores, and comfort with living for decades in the shadows, quarantined from public attention. It’s one that has made Liemandt, now 56, worth more than 10 times what he was when he appeared on the Forbes 400 nearly 30 years ago. It’s the kind of worldview that is likely required to one day, seemingly on a dime, pivot from the difficult problem of configuration to the even more impossible problem of education.

“When GenAI hit, I thought, ‘Oh, neural nets, it’s finally here,’” Liemandt said as we rode in his Cybertruck across Lady Bird Lake to MacKenzie Price’s Alpha School, where for the last three years he’s been able to capture an enormous amount of data. “So I went to my Trilogy team, who’ve all been with me for decades. And I’m like, ‘For 25 years you guys have been telling me you could run this place better than me. Let’s see. Good luck. I’m out. I’m going to go be a school principal.’”

Liemandt was the best man at MacKenzie’s wedding to Andy Price in 2004, and they stayed close as the Liemandts and Prices each had two daughters, who grew up together. When the girls were small, he started to think seriously about the contribution he wanted to make with his fortune. As someone who’d hated school and wanted something different for his own kids, he decided on education.

One early project he and Price collaborated on was funding a randomized control trial by the Harvard economist Roland Fryer, who experimented with paying fifth-graders at bottom-ranked schools in Houston to complete their homework and get good grades, and parents to attend parent-teacher conferences. Fryer found that the payments affected effort but not results. “It’s like telling a random person you’ll pay them $10 million to win Wimbledon,” Price explained. “It’s hard to incentivize outcomes, but you can incentivize the work itself.” (Told their finding was scientifically replicated by a software tycoon and a Harvard economist, Taco John’s could not be reached for comment.)

Like many philanthropic billionaires, Liemandt also spent years sinking money into nonprofit education reform efforts that went nowhere. And like many parents, Liemandt and Price both initially decided to give their children the schooling experience they themselves hated: Liemandt put his in a Catholic school, while Price put hers in public. Both schools were highly ranked in Austin. Both drove Liemandt and Price insane.

Liemandt, for example, would go with his wife to a parent-teacher conference and ask how his daughter was doing. “We’re so excited to have her in class,” the teacher would say. “She’s so sweet.”

“Right but how’s she doing?” Liemandt would ask. “I’m not a domain expert here, you’ve gotta give me something.” His kid, every bit her father’s daughter, liked reading math textbooks from a young age.

“She’s just great,” the teacher would say, “we love having her.” Liemandt would see red until his wife asked him to stop attending parent-teacher conferences, which he did.

At the same time, Price would volunteer at her daughter’s school, and visited one day at lunchtime. She sat down with her daughter in the cafeteria, where each student was assigned a particular seat. Across the table from them, a boy raised his hand at no one in particular.

“What do you need, honey?” Price asked the boy.

“Ketchup,” he said. The ketchup bottle, Price noticed, was standing on the table inches away, closer to him than she was.

“Well, there it is, buddy,” she said. “Go ahead and take it.” But the boy just kept his arm extended in the air and looked around nervously.

“He has to get permission from the cafeteria monitor,” Price’s daughter informed her.

“I’m an adult,” Price said to the boy, “and I’m telling you you can take the ketchup,” which in the Eanes Independent School District, the highest ranked in Austin, was like telling a North Korean border guard to cross the 38th parallel and promising he’d be fine.

Like Liemandt’s eldest daughter, Price’s was also a precocious reader. By kindergarten she was reading chapter books, but would come home from school with worksheets that said things like A is for Apple, B is for Ball, etc. By second grade, when Price attended a parent-teacher conference, her daughter’s teacher delivered the good news that she was reading at a second-grade level.

“That’s strange,” Price said. “At home she’s reading Harry Potter.”

“Oh she’s way past second-grade level,” the teacher said. “We’re just not allowed to teach beyond grade level.” Price went to the school’s principal and asked what could be done about this. “I understand your frustration,” the principal said. “But we’re steering the Titanic here. It just can’t be changed.” When her daughter woke up one morning and asked if she could stop going to school because it was boring, Price, too, saw red.

“That was when I knew I couldn’t watch another 10 years of this,” she told me. “I knew at that point that it wasn’t about going to another public or private school. It was about the model of a teacher in front of the classroom, teaching in a time-based model where they have a certain curriculum they have to stick to and the kids, regardless of their different interests and capabilities, are stuck in it no matter what. So I’m thinking, okay, we gotta start something else.”

In 2014, Price started Alpha School (initially called Emergent Academy) with Brian Holtz, then a parent at Acton Academy, another experimental microschool in Austin. They began in Holtz’s house with 16 kids, including the Price girls. The idea was for students to self-direct learning at their own pace using the EdTech tools of the time—Khan Academy, ALEKS, Math Academy, Newsela, DreamBox, EGUMPP, etc.—with Holtz in the role of motivating coach and guide. Each day, once students completed their coursework on the apps, they would do things like girls v. boys neighborhood lemonade stand wars, or Hero’s Journey performances, in which they’d each study a famous figure, dress up like them, and answer questions in character. Price’s belief in every kid’s idiosyncratic interests and the freedom to follow them appeared vindicated by the fact that one of her daughters chose Malala Yousafzai, while the other chose Tory Burch.

Over the first two years, Price kept encouraging Liemandt to send his daughters to Alpha School, not least because she could have used his help. After moving the students from Holtz’s house into a rental property, they were served an eviction notice due to neighbor complaints about the abrupt appearance of a school in their midst. They then moved the students into another parent’s house for two weeks before using a parking garage. At one point Price was closing on a deal to obtain space in a real building when the real estate agent in charge of selling the property pulled up outside of school one day and asked Price to get in her car. “I have the Holy Spirit gift of discernment,” the centrally cast Texas realtor told Price, who sat in her passenger seat with all the windows closed and doors shut. “I am very good at seeing and understanding evil spirits. And I believe that you are of the devil.”

Nevertheless, Alpha students were starting to approach the 2x in 2 hours target by self-directing coursework on apps. More importantly, despite the lack of an actual schoolhouse to occupy, they had started to plead with Price and Holtz to keep Alpha running during winter, spring, and summer breaks, preferring to stay in school rather than go on vacation. The signs were good that Price was onto something.

Still, at that point, Liemandt was unimpressed. “I was like, MacKenzie, I’m not sending my kids to your weird, janky school,” he told me. “It was in a dude’s garage. I was like, no way. I went to Catholic school and my kids are going to Catholic school. I didn’t want to do it.”

Two things eventually changed his mind. The first happened one night when Liemandt and Andy Price took their daughters out to dinner. The Liemandt girls had gotten into an argument, and their father mentioned that it was kind of fun to hear both of their perspectives. Confident in his own kids’ literacy, Liemandt turned to the Price girls and asked if they understood what he meant when he used the word “perspective.”

“Yeah,” said the younger Price sister, then in first grade. “It’s kind of like the way the Japanese look at World War II compared to Americans, or the Italians versus the French.”

The second one happened at the end of the school year. The Liemandts’ Catholic school got out in May, and the girls had a couple weeks before summer camp began in June. The Price girls convinced them to come shadow at Alpha School for a week before camp. “If you want to go to a school instead of vacation,” Liemandt told them, “that’s crazy, but go ahead. It’s your break.”

After their shadow week, they sat their parents down for a talk. “We’ve decided we’re not going to summer camp this year,” they informed Liemandt and his wife. “We want to go back to Alpha.” That summer, he grudgingly took his kids out of Catholic school and put them in Price’s weird, janky school.

Liemandt decided that Holtz’s central idea—‘kids must love school so much they don’t want to go on vacation’—was not the platitude of a principal but an achievable outcome that could be broken up into component parts and systematized, and which in turn could change the lives of his kids and possibly others.

“What are the things I’m not understanding here?” Liemandt asked Holtz during his first parent-teacher conference at Alpha School.

“Your kids must love school,” Holtz said. “I mean really love school.”

“Right, like spinach,” said Liemandt. “I get it. What else?”

“Your kids can do much more than you think,” said Holtz. “Your standards are too low.”

“Oh, my standards for them are pretty extreme,” said Liemandt.

“No, they’re not,” said Holtz. “They can learn twice as much as they were learning at your old school, and they can do it in two hours a day. Talk to me in 100 days.”

The EdTech apps were fairly primitive at the time, Alpha School wasn’t quite hitting its two-hour target yet, and Price and Holtz were continually in search of a space that wasn’t someone’s living room or parking lot. But the fragments of the idea were there, and in the case of Liemandt’s daughters, after 100 days, it seemed to be working. They didn’t want to go on vacation or to camp anymore, and they were learning a lot more than they had been in Catholic school. At a certain point, Liemandt decided that Holtz’s central idea—“kids must love school so much they don’t want to go on vacation”—was not the platitude of a principal but an achievable outcome that could be broken up into component parts and systematized, and which in turn could change the lives of his kids and possibly others.

As a result, Liemandt did what he’d always done: He huddled in a nook and tore through books and research papers. He calculated that education, which had no good products in existence, was a potential trillion-dollar market. And he made himself into an expert—this time, on “learning science.”

Unlike the problem of configuration, the findings of learning science are pretty intuitive.

Think of it like this: Way back when, it was understood that human beings between the ages of five and 18 were capable of a lot. Mozart was composing symphonies at age five, Alexander was plundering the Maedi at 16, etc. True, many billions more human beings were farming dirt and strangling each other in smoky windowless huts, or whatever people did. But many of the great geniuses of history had in common a childhood spent in “aristocratic tutoring”: dedicated adult experts who provided one-on-one instruction across a range of subjects to their young pupils. Marcus Aurelius, John Stuart Mill, Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein, and many other eventual geniuses enjoyed some version of this.

It was never, of course, an educational model that could scale to every member of a society. In the Industrial era, the “factory‐model” classroom arose as a way not to produce more Alexanders, but to mass-produce basic literacy and civic conformity. Inspired by Prussian schooling and favored by American industrialists, the factory-model classroom consisted of an 800-square-foot room in which one teacher lectured to 20–30 similarly aged students, who were herded into rows of fixed desks for six hours a day, for 13 years. The type of student that excelled in this environment was not a Mozart or a Mill but a child in possession of copious amounts of what the Germans called Sitzfleisch (literally, “sit-meat”), the ability to sit still, perform tasks, receive standardized information, and do other things Germans admire for excruciating periods of time.

You might have noticed that between Bismarck and Friedrich Merz (the current German chancellor; it’s a good thing we don’t have to know their names anymore), not much has changed about school. And not just in the West. Whether you’re at Horace Mann or from a slum in Mumbai, “school” looks something like 20–30 same-age students seated in fixed rows receiving standardized information from a teacher in a classroom. When people talk about “hating school,” this tends to be the image etched underneath their eyelids.

To be fair, as Liemandt and Price both told me repeatedly, “Good schools have always been good teachers, and good teachers are awesome; it’s the model of ‘a teacher in front of a classroom’ that’s the problem.” For a long time, moreover, the industrial classroom clearly did not inhibit millions of people from achieving the American dream, and in many cases was primarily responsible for making it possible. It was also fantastically effective at assimilating vast numbers of human beings from owner-occupied farms into manufacturing and clerical work, and more generally from 18th-century agrarianism into the mass urban political societies of the 19th and 20th centuries.

But in the 21st century—to put it so mildly as to risk trivializing the scale of the crisis in plummeting outcomes—its returns have diminished. Learning science is the academic field that attempts to explain why.

Its seminal findings and theories include Bloom’s 2-sigma problem (1984), which posits that average students who receive one-on-one tutoring in subjects to “mastery level” (i.e., requiring a minimum of 90% rather than 72% to advance) score roughly two standard deviations higher than students in conventional classrooms; Cognitive Load Theory (1988), positing that instruction works best when it manages a student’s “limited working memory” by eliminating extraneous information and directing mental effort toward concepts useful over the long term; the “zone of proximal development,” meaning the optimal point between material that’s not too easy and not too hard for a given student, where they’re scoring about 80–85% at any given point (a principle best understood by video game designers); and the inferiority of inquiry learning (in which students “discover” concepts through “exploration”) compared with direct instruction (Just tell us what we need to know!).

There is also spaced repetition, dual coding, metacognitive reflection, interleaving, and various other techniques with names I learned in the last few weeks but about which I have no point to make (other than that it takes a learning scientist to refer to any pothead’s favorite pastime—thinking about how you’re thinking about the thoughts you’re thinking about—as “metacognitive reflection”). If the consensus of learning science could be summed up in a sentence, it would be that “a teacher in front of a classroom” is one of the least effective ways to teach kids anything.

If many of the findings of learning science sound obvious, it’s because most of it was also obvious in the 4th-century BC, and perhaps even in the 1980s at Taco John’s. The problem is that a teacher cannot simultaneously manage the “cognitive load” or “zone of proximal development” of 25 kids at a time, any more than a state can aristocratically tutor an entire continent of them. Which is why, for its first eight years, Alpha School came in for some harsh criticism.

As its students really were starting to achieve “mastery-level” test scores at twice the speed of their peers in conventional private schools in something approaching two hours a day, people pointed out that the kinds of parents who send their kids to an expensive, teacherless, app-based private school are probably the kinds of parents who reproduce fast-learning, high-scoring offspring. In a word, Price and Holtz were accused of propping up impressive results with what academics refer to as “selection effects” (“cherrynugging,” in pothead): They had a school full of rich kids and were getting rich-kid results. (There is a catch: Like other private schools, Alpha School is expensive at $40,000 per year at the Austin location; unlike other private schools, however, it does not screen for academics or test scores in admissions.)

Even Liemandt, whose daughters were thriving there, remained skeptical. “It’s really great what you’ve got here,” he told Price. “But it’s like everything in education: It’s not scalable. You can’t scale this to the world.”

Making Alpha School planetary hadn’t necessarily been Price’s ambition at first; she’d just started a weird, janky school for her kids and made it available to other families in Austin—maybe with the intention of expanding it elsewhere in Texas, and perhaps one day to other states.

But it never would have occurred to Liemandt to think about it that way. How could he? He’d been thinking in massive, intricate systems, and Jack Welch-sized business possibilities, for 40 years, with few experiences that would have furnished him with a feel for limits. “Joe is 98% the most normal guy ever, and 2% the craziest freaking dude,” said a collaborator who asked to remain anonymous. “His sense of scale, how bold his vision is, his ability to overcome friction. When you’re in his presence, you can feel the waves of time and space bending to his vision. Things just seem possible with him that aren’t true in normal life.”

During his 25 years of solitude, when he became a father and started weighing the ends to which his abilities and resources might be put, Liemandt also felt the shape of his own vocation changing. He was still married to the game of business success, but began to see his prior life—both his misery as a student and his achievements as an entrepreneur—as simply a preparation for the challenge of making “school” something every kid loves, and of making the immediate future, in his words, “the best time in human history to be a five-year-old.”

Joe is 98% the most normal guy ever, and 2% the craziest freaking dude. His sense of scale, how bold his vision is, his ability to overcome friction. When you’re in his presence, you can feel the waves of time and space bending to his vision. Things just seem possible with him that aren’t true in normal life.

“There is always an instrument invention that causes the inflection of a science,” Liemandt said, as we sat in a lunchroom at Alpha School’s elementary campus, an electric-blue modernist schoolhouse that looks equal parts art studio, tech company, and treehouse, tucked away in the dappled shadows of Hill Country live oaks off the MoPac expressway. “Biology, chemistry, physics, they all had their days of wandering in the wilderness. Doctors were bloodletting, chemists were blowing themselves up. But then there was the microscope for biology, and the analytical balance for chemistry, the telescope for physics. The instrument invention allows a more precise measurement, and that precise measurement is what allowed those sciences to take off.”

“Learning science has sort of been that way. It’s in this wilderness period for 40 years where we have 10,000 papers, but you run an experiment in a classroom, and you have no idea what the teacher’s going to teach. You have no idea about the students. Are they motivated? Are they spinning in their chairs? Are they even paying attention? Do they have the prereqs? Do they know the algebra they need to learn chemistry? And so the data is dirty. The environment is like pre-analytical balance. You don’t have the resolution.”

“AI is the instrument inflection for learning science,” he said. “Not chatbots. If you deploy ChatGPT to every student in America, we will become the dumbest country on the planet. Rather it’s the learning engine GenAI’s allowed me to build that can generate personalized lesson plans for every kid that are 100% engaging. It can track their knowledge graph [what they know and don’t know] and their interest graph, and dynamically teach curriculum by analogy to the things they care about.”

“And with our vision model, you can monitor it all—the anti-patterns, the habits slowing them down, the mistakes they make, the time they’re wasting. You have precise instruction, precise data that you can feed back into the generation engine. So now we have this closed loop that no one else has. That’s how we get these crazy results—kids learning 2x, 5x, 10x more in two hours. People think it’s witchcraft, but it’s literally just science. That’s how we have third graders doing seventh-grade math; it’s how we can take a kid who the conventional school system considers ‘two years behind’ and catch them up in 40–60 hours. It’s how we give kids their time back.”

“That’s why when GenAI hit in 2022, I took a billion dollars out of my software company. I said, ‘Okay, we’re going to be able to take MacKenzie’s 2x in 2 hours groundwork and get it out to a billion kids.’ It’s going to cost more than that, but I could start to figure it out. It’s going to happen. There’s going to be a tablet that costs less than $1,000 that is going to teach every kid on this planet everything they need to know in two hours a day and they’re going to love it. I really do think we can transform education for everybody in the world.”

“So that’s my next 20 years,” he said. “I literally wake up now and I’m like, I’m the luckiest guy in the world. I will work 7 by 24 for the next 20 years to fricking do this. The greatest 20 years of my life are right ahead of me. I don’t think I’m going to lose. We’re going to win.”

“I’ve never had anything like Timeback. Never had a product that’s so much better, 10x better than the competition. Ever. In my entire career.”

While certain details remain secret, and the product is not yet ready to ship, the demo I was shown in August from Liemandt’s lab in downtown Austin lent credibility to his claim.

The lab is staffed by about 300 people, consisting of longtime Trilogy programmers and what Liemandt calls “probably the biggest, best team of learning scientists in the world.” Like past Liemandt ventures, the project suffers a bit from too-many-brands disease. But it can be summarized, roughly, as follows:

Liemandt’s core generation engine is called Incept, which is like a custom-tailored large language model. At the heart of Incept are third-party, general purpose LLMs (OpenAI’s GPT-5, Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4, Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro, etc.), each of which is best at a particular function, like generating math problems or learning videos. The core, off-the-shelf LLM is then wrapped in various proprietary tools to ensure curriculum alignment, generate the correct images and feedback, and inject strong points of view about learning science, including direct instruction, spaced repetition, eliminating extraneous information, mastery-level advancement requirements, and teaching by analogy. With continual tweaking by the Trilogy programmers and learning scientists, it also, over time, has driven hallucinations down close to zero. (It’s important that in the World War II curriculum, for example, the Nazis are not Black.)

Incept also maintains a unique data structure for every user—what they know and don’t know, what they’re passionate about, their cognitive load profile, their zone of proximate development—which enables it to generate personalized lesson plans for each individual student. The “minimum” plans Incept generates teach state-mandated curriculum and required material for standardized tests, though depending on a student’s progress and success in achieving mastery-level on their “minimums,” it can also generate personalized lessons on anything from James Joyce to quantum gravity.

The name itself has a double meaning: In medieval Oxford and Cambridge, “inception” was the term for formal admission to the degree of Master of Arts, which granted the right to teach. In the related jargon of the Christopher Nolan movie, “inception” is the act of starting an idea inside someone’s mind. “The name comes from both parts,” Liemandt says. “It’s putting a mind virus into a kid’s head, which is what education is. And it’s being done by a teacher you trust.”

The layer above Incept is Timeback, the operating system that replicates in software the experience of having a one-on-one human tutor. Timeback’s primary tool is the vision model that monitors and records a student’s “anti-patterns,” meaning habits that make learning less effective, like rushing through problems, spinning in your chair, socializing, checking Instagram, or “topic-shopping” (abandoning a subject and switching to another when it gets hard, which is a primary shortcoming of all legacy EdTech apps).

The data generated by the vision model (literally, a raw video stream of the user) is then fed into an ever-present “waste meter” that shows the student how much potential free time they’re losing by not completing their lessons in the target two hours. It also generates coaching and feedback based on both the individual student’s data structure and the data collected from all other users, the way Tesla aggregates data from all car trips to make over-the-air software updates that improve each vehicle long after it’s left the factory. Together with Incept, the Timeback vision model is able to tell whether a student is struggling to reach mastery-level because they’re screwing around, or because they haven’t reached or retained mastery of prerequisite material (like not knowing the algebra required to learn chemistry). If it’s neither, Incept will regenerate the lesson plan to teach the material in a different way or via different analogies. (The vision model also works as a proctor during test-taking and, of course, ensures that students—and their parents—aren’t cheating.)

Timeback additionally serves as an app store that hosts various third-party apps (Khan Academy, Duolingo, Math Academy, etc.) and the proprietary apps Liemandt’s team has built on Incept, including AlphaWrite (using AI to teach you to write rather than cheat), Athena (learning videos and multiple-choice problems for every subject under the sun), TeachTales (dynamically generated stories for reading comprehension), TrashCat (a Subway Surfers-like video game focused on learning speed), and TeachTap (essentially a clone of the TikTok interface and scrolling experience, but with Incept-generated educational content).

It’s putting a mind virus into a kid’s head, which is what education is. And it’s being done by a teacher you trust.

–Joe Liemandt