Click here to subscribe to print for your office or home.

Picture him in the middle of nowhere, in Guangzhou, which back then was still a torment of factory exhaust and steel. It is 2007, and Neil Mehta is 24. He is tall, about six foot two, but looks tiny beneath the only other thing standing in the vast empty space, a giant apartment building, which is going for about $35 million. Mehta is here to purchase it at auction.

He is living in Hong Kong, in the heady expat district of Lan Kwai Fong, but he’s been dispatched here to Guangzhou by a subsidiary of D.E. Shaw, the hedge fund, to bid on this big apartment building in the middle of nowhere. He’s coming in with real heft at his back, Goldman and the like, so Mehta shows up to the auction representing the good offices of D.E. Shaw in a smart jacket and slacks, which is uncomfortable because it’s humid and hot, and he had to take a train and then a cab which followed some guy on a motorcycle who claimed to know where this building in the middle of nowhere was but couldn’t find it until the third try.

So imagine Mehta’s surprise when he gets to the auction, which is just a bunch of lawn chairs creaking wanly on the empty ground beneath the building. In front of the chairs is a wooden podium and an auctioneer handing out paddles. Mehta takes a paddle and sits next to his competition for the $35 million building, a farmer with a paunch in a wife beater smoking a cigarette. The tendrils of smoke curl slowly in the humid air, and the lawn chairs creak, and in the weird little Wes Anderson movie his life has become, Neil Mehta looks up at the big building in the middle of nowhere and smiles, probably.

Later that night he is in Shenzhen, to visit the offices of BYD. In 2007 BYD was not yet a $600 billion conglomerate vaporizing the German auto industry. It was a seemingly fraudulent goat rodeo of a company making batteries for frivolous little ‘electric cars’, in a dank warehouse in a city that was still in the process of transforming from a fishing village. When Mehta walks into BYD he notices liquid dripping down from the ceiling onto the floor, which isn’t the kind of thing you prefer to see in a place manufacturing lithium iron phosphate batteries.

The place is just a mess, but it doesn’t really bother Mehta. He loves it, in fact. He’s obsessed with this idea that electric vehicles are going to be a big thing, and he loves the energy of the place. He especially likes talking to the people there about the company’s Founder, Wang Chuanfu. Mehta loves hearing about Wang. It’s been all well and good learning about Mongolian commodities and Australian housing and apartment developments in Guangzhou at D.E. Shaw in Hong Kong, but Mehta realizes he’s got this thing about founders. He really, really likes them.

He likes them a little too much, maybe. At one point he meets the founders of this animation studio called Imagi making a Pixar-style movie about Astro Boy, the postwar Japanese manga, and he loves spending time with the founders so much he raises $3 million to keep Imagi afloat when it’s approaching bankruptcy at about 17 cents a share. The 24-year-old Mehta saves Astro Boy from certain death and when it comes out, the critical consensus is that it’s something like the worst animation movie ever made. But it’s got Nicolas Cage and Kristen Bell doing voices and enough people see it that Imagi’s stock price climbs back up, and in a few months Mehta makes over three times his money on a company staring at bankruptcy.

Which isn’t even really the point. The point is that he loved spending time with the founders and being their closest partner at the lowest point in their lives and seeing it through until their heads were back above water. It’s the kind of thing he starts doing more and more, on nights and weekends, on the margins of his job investing in distressed real estate, buying distressed banks, flying through torrential Hong Kong downpours in a single-engine helicopter to Macau to negotiate financing for luxury hotels, and all the other stuff a young associate in the special situations group at D.E. Shaw has to do. Mehta gets this idea into his nut that what he should really be doing with his life is being the best partner a founder’s ever had.

Now it’s August 2008, the Olympics, and Mehta’s in Beijing to watch Michael Phelps compete in the 4×100-meter medley relay. Mehta is sitting in the stands in the Beijing Water Cube and the lights go down, the meet is about to start.

He was here in this same spot just a week earlier, watching Phelps swim a different meet, and when the lights went down that time everyone just watched the meet. This time, though, the lights go down, and Mehta, clutching his BlackBerry Messenger, notices that the faces of everyone in the stands are illuminated and looking down at their laps, as if they’re boycotting Phelps’ dominance by refusing to look at it.

By now it’s a familiar sight—the lights go down in a movie theater, and everyone’s face is lit up blue by their iPhone—but BlackBerries didn’t do that, and back in the summer of 2008 the iPhone was only a year old, so it was still a weird thing to see. He asks a friend next to him what the hell everybody’s doing, and the guy says they’re all on QQ. Everyone in the stands has some version of an iPhone knockoff HTC smartphone, and they’re all on QQ, the precursor to WeChat.

Mehta goes back to his apartment in Hong Kong after the meet and looks it up. QQ is going from near zero to racking up more than 30 million users a quarter, the growth curve is pointing to 100% penetration. Insane! Mehta calls Benny Peretz, his friend at D.E. Shaw in New York and his little brother’s old college roommate, whom he first bonded with a few years earlier at the UPenn Spring Fling, which they spent discussing the arcana of European cruise ship financing. “This is it,” Mehta says to Benny about his Water Cube epiphany. “We don’t get to be around for many of these in life. This is the kind of thing we should be doing.”

By this point Bear Stearns had already crashed, and when Mehta went to the brass at D.E. Shaw to explain why they needed to be investing in private technology companies right now, Lehman Brothers collapsed a few days later. Among other things, there’d been too much credit going around, which is why provincial farmers were bidding on $35 million apartment buildings. Every TV at D.E. Shaw was plastered with footage of men with ties slung over their shoulders wandering around Wall Street holding their life in a box. In other words, Mehta’s superiors were not interested in hearing from a 24-year-old associate just then about how these mobile smartphone apps have zero marginal cost, you just write lines of code, you deploy it on a platform for free, there’s a network effect—it’s all so sick!

By 27 Mehta’s seen enough, and he’s left D.E. Shaw to start a firm with his friend Benny. On a whim he calls it Greenoaks, after the street in Atherton, California where he grew up. In the first deck for Greenoaks there’s a slide called ‘Finding Value in Unusual Places’, which at the time meant the internet. The idea was that these internet companies, these unbelievably cheap businesses, were going to replace a large percentage of the S&P 500. In 2012, he bets 40% of his first fund on Coupang, an ecommerce retailer in South Korea, led by a founder, Bom Kim, whom Mehta’s fallen head-over-heels in love with. Greenoaks soon owns upwards of 15% of the company, and eventually returns about $8 billion from that one investment.

Today Mehta is 40, and over its first 13 years, Greenoaks has played a legendary part in the rise of Coupang, Figma, Wiz, Carvana, Stripe, Discord, Rippling, Toast, Robinhood, and other unicorns led by N of 1 founders, generating over $13 billion in gross profits, a 33% total net internal rate of return, and only about a point of principal impairment. The firm is unusually small and concentrated: five funds of 55 core companies across nearly $15 billion of assets managed by nine investment professionals—with Mehta himself as one of the largest LPs in each fund. Henry Kravis, one of the first LPs, told me that at the top of the market between 2020–2022, Greenoaks probably returned more money to investors than anyone else. “Neil’s extremely disciplined, he’s gone against the tide many times, and he’s had exceptional timing,” Kravis said. “He’s the real deal.”

The firm has now achieved icon status among founders and investors—but casual observers more familiar with names like Sequoia and Andreessen Horowitz might have come across Greenoaks for the first time only recently. In February 2025, Bloomberg reported that Ilya Sutskever, one of the founding fathers of modern AI, raised over $1 billion for his startup, Safe Superintelligence (SSI), at a valuation of more than $30 billion—six times what it was less than six months before. Leading the deal, according to reports that neither SSI nor Greenoaks have confirmed or even acknowledged, is purportedly Mehta’s shop, with an investment of over $500 million.

SSI operates in complete secrecy, and says it doesn’t plan to release a product until it develops artificial superintelligence—the term for a machine that would far surpass human intellectual capabilities in virtually every domain—as distinct from the artificial general intelligence (which would merely match or slightly exceed human-level cognition) being developed by foundation model companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI. But Sutskever, the former Chief Scientist and Co-founder of OpenAI, recently made the tantalizing claim that he’s identified a “different mountain to climb” from the model companies.

Over several weeks of interviews, in which he opened up to a reporter for the first time, Mehta declined to comment on SSI. But a potential clue into the matter, and into our future as a species, might be gleaned by peering into the life and work of Mehta himself, who over a dozen founders and investors interviewed for this story variously compared to Warren Buffett, Masayoshi Son, and Elon Musk—often in highly emotional tones.

Bom Kim, who is normally the Bill Belichick of tech when it comes to interacting with reporters, agreed to speak at length with Colossus Review about Mehta. “From the day we met,” he said, “I’ve believed that Neil is going to be a household name.”

CAROLYN FONG

“I’m best friends with my parents,” Mehta told me on a miserably wet morning as we walked through his Pacific Heights home, where an agreeable playlist of Bob Dylan and Amy Winehouse played quietly on surround sound. His favorite part of the house are the three kids’ bedrooms, which are vestibuled like a passenger train, with double sliding doors connecting each room to the other. “I’ve never had a bad day with my parents.”

As yours might have done, my eyes rolled back into my skull when I first heard Mehta say things like this, which in this case he did as ‘Visions of Johanna’ played from the small white speakers in the ceiling of his living room. Yet as I eventually sensed, such sentiments are frank and deadly serious, and part of the key to unlocking Mehta’s unusual genius for both business and partnership—and to dissolving the cynicism one initially feels when they observe the apparently unaffected bounce in his step.

Mehta’s parents, Nitin and Meena, grew up in the slum town of Palanpur, in the state of Gujarat, and later came to America in the first great wave of Indian migration that began after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 abolished the national-origins quota system established in the 1920s, replacing it with a skills-based preference system. At the time, Gujaratis had mostly dominated the hotel, restaurant, and retail trade sectors, while IT was mainly the preserve of Telugus and Tamils. But like many Indian immigrants to America of the time, Nitin was an engineer, and came to Rapid City in 1967 to attend the South Dakota School of Mines & Technology, before spending a long career at McKinsey.

Many of Mehta’s earliest memories are of obsessively discussing business with his father, like the time they returned home from a fifth-grade classmate’s mini-golf birthday party at the Malibu Grand Prix in Redwood City. For most children, the outcome of having fun at mini-golf is that they want to play more mini-golf, perhaps even golf. But the fifth-grade Mehta had so much fun that he wanted to “get into the mini-golf business,” and so he and his dad modeled it out on Excel. “I can’t remember a day when I wasn’t talking about businesses with them,” he said.

There was also the time they visited Niagara Falls, when Mehta was 11. They woke up at the crack of dawn, and his dad piled Neil into several coats before boarding the Maid of the Mist for a freezing cold boat tour. It turned out the Maid of the Mist was basically a motorized sardine can that rides out to the Falls for a quick photo and then turns around and comes back. Aghast, Mehta checked the tour tickets and noticed they were 15 bucks a pop (this is the 90s, mind you). So the boat docks and one of the deckhands is just standing there, letting all the frozen begoretexed sardines off the tour, when a small Indian child obscured by multiple layers of down walks up to him and demands to know why no one is competing with them for prices. The apparently forbearing deckhand informed Mehta that Maid of the Mist has an exclusive concession over the port that grants them a monopoly.

The experience led Mehta to an interest in the idea of cornered resources, and he started looking into aquariums, Six Flags Magic Mountain, and Madame Tussauds (“No one’s going to build a second wax museum in London,” he remembers thinking). “I loved sports, but I had a terrible jump shot, I wasn’t that good at soccer, I’m not that fast,” he said. “I was captain of my debate team, but I wasn’t that proud of it. What motivated me was investing in companies, even back then.”

In high school, Mehta was a shiftless student who skipped class and soccer practice, and was kicked out of Spanish for refusing to speak anything other than English. He made money on the side as a top-ranked door-to-door seller of Cutco steak knives, cleaning up from stay-at-home moms with discretionary income in suburban Silicon Valley. He also tried launching a company called Zymst, an online high school yearbook catalog where students could edit their written comments on someone else’s photo from the previous year, based on whether they still liked them or not. When he graduated, he was given a card, signed by his teachers, which read, “Remember, Neil: In real life, detention is called jail.”

Mehta wasn’t motivated by money, per se. “It was more like a puzzle, like a mathematical equation,” he said. “It was deducing things down when there’s all these various opinions. And when you’re young, so much of your life is like, you’re being told, ‘this is the way the world works’. So this was one of the only ways that I knew how to express myself, that maybe I had differential insight or opinions, and maybe the world doesn’t work exactly like they say. And then when you’re right, it feels really rewarding, especially when you’re young.”

“Not exactly,” he said, when asked if his interest in founders in particular only came later. “A lot of my view of the world was formed from my grandfather,” a Jain from Ahmedabad, about a three-hour drive from Palanpur. “He was very simple, grew up dirt poor, and he owned a little gun shop. He sold old pistols and rifles from the Maharajahs. He loved art, he loved music, and guns to him were the equivalent of architectural masterpieces. He’d spend hours explaining to me a scene crafted on the husk of a gun, telling me the story of why it was crafted. It would be like an hour-long story, and I’d be captivated.” Starting when Mehta was nine, his grandfather would set up balloons and bottles outside the garage of his home in Mumbai and teach Neil and his younger brother to shoot them, to their mother’s horror.

“He cared a lot about quality, a lot about craftsmanship. He cared a lot about heritage. When you’re young, these aren’t concepts that you immediately understand. The finishings of a pistol, or the colors that were put into a rifle 120 years ago, and the relevance of why these colors were picked … I think it was imbued in me fairly early from my grandfather that producing things of value, producing craftsmanship, caring about the quality of finishings, caring about the artistic beauty of something—those are things that could bring out enormous joy in life.”

“Then if you pair that with my dad’s influence,” he continued, “I became a big believer in capitalism, really company formation, as the primary source of human progress. I’m a fervently religious believer in capitalism … So the reason I do what I do is because I want to be a small part of being in service to the people creating those companies in the capitalist structure that allows humans to progress. And the quality and the beauty and the finishings of how they do that, and how they deliver it to humanity, are really important to me. I think it all comes from my grandfather, and some of it from my dad.”

Mehta pointed me to an internal Greenoaks document called ‘Our Soul’, in which he explains the firm’s relationship to founders. “I never really made the connection until now,” he said, as we sat in a conference room at the Presidio offices of Greenoaks. “I’ve never said this out loud. My wife doesn’t even know most of this. But it does feel kind of obvious as I say it: There’s a part in ‘Our Soul’ that’s directly attributable to my grandfather. Which is that I talk about founders as artists. ‘Each one’s painting their own painting.’”

“In the document, I tell the team: It’s easy to have opinions and spend other people’s money. But that’s not our job. We’re in the business of understanding what founders are doing, and being humble and curious and empathetic about it. Our job is to figure out how and why they’re painting their painting. That’s it.”

“It’s so easy to be an art critic,” he said. “Understanding what a painter’s actually trying to do—that’s the hard part.”

Agony can be hard to spot in the bright life of Neil Mehta, but an early bout arrived during his freshman year of college, when he abruptly left California for Mumbai, where his grandfather was dying.

Mehta was 19, and the Asha Parekh public hospital in Mumbai was about as rough as you’d think. “I had a hard time digesting it,” he said. “Really, he raised me. My parents were amazing. But my dad traveled a lot, and my grandfather was the closest person. It felt like I had this person who was also my fan and always there for me, and no matter what happened in the world, I’d be able to talk to him and have his support and love … In Mumbai, that was the first time I was like, Oh. It’s just going to be me.”

To alleviate the loneliness of his grandfather’s hospital room, Mehta tried calling his girlfriend, whom he’d been dating since high school. It was 2002, and the only phone available was one of those ridiculous white hospital landlines with hundreds of buttons. They’d agreed on a time to speak, but Mehta called her something like 10 times with no answer. After several hours he finally got through to her, and while Mehta stood in the dingy hovel where he would shortly lose the most important person in his life, his girlfriend said to him, “I want you to know something, Neil. I don’t love you anymore.” And then she hung up the phone.

“Never talked to her again,” he said, like a boy whose dog ran away but is trying to be brave about it. “And I was like, well. This fucking sucks.”

It wasn’t the Siege of Leningrad, exactly. But Mehta didn’t handle it well, at least by his standards. He went home to Atherton and hung around Santa Clara University, going to class less and less, opting instead to swim ponderously at the YMCA pool, smoke a lot of weed, and read Schopenhauer and Victor Frankl, as is a heartbroken young man’s balm. “My mom was really worried about me,” he said. “My dad was like, he’ll figure it out. I would just roam around. But I enjoyed the wandering. My parents never rushed me to get out of it. They were awesome about it, in retrospect. I owe them a thank you for that. For just letting me have space to wander.”

‘Wandering’ for Mehta took all of a semester, at which point he looked in a mirror, he said, and told himself that it was the last bad day he’d ever have, as if it was his choice. “I’ve worked really hard to make every day better than the previous one since then. My grandfather would tell me that all the time. I try to live by that.”

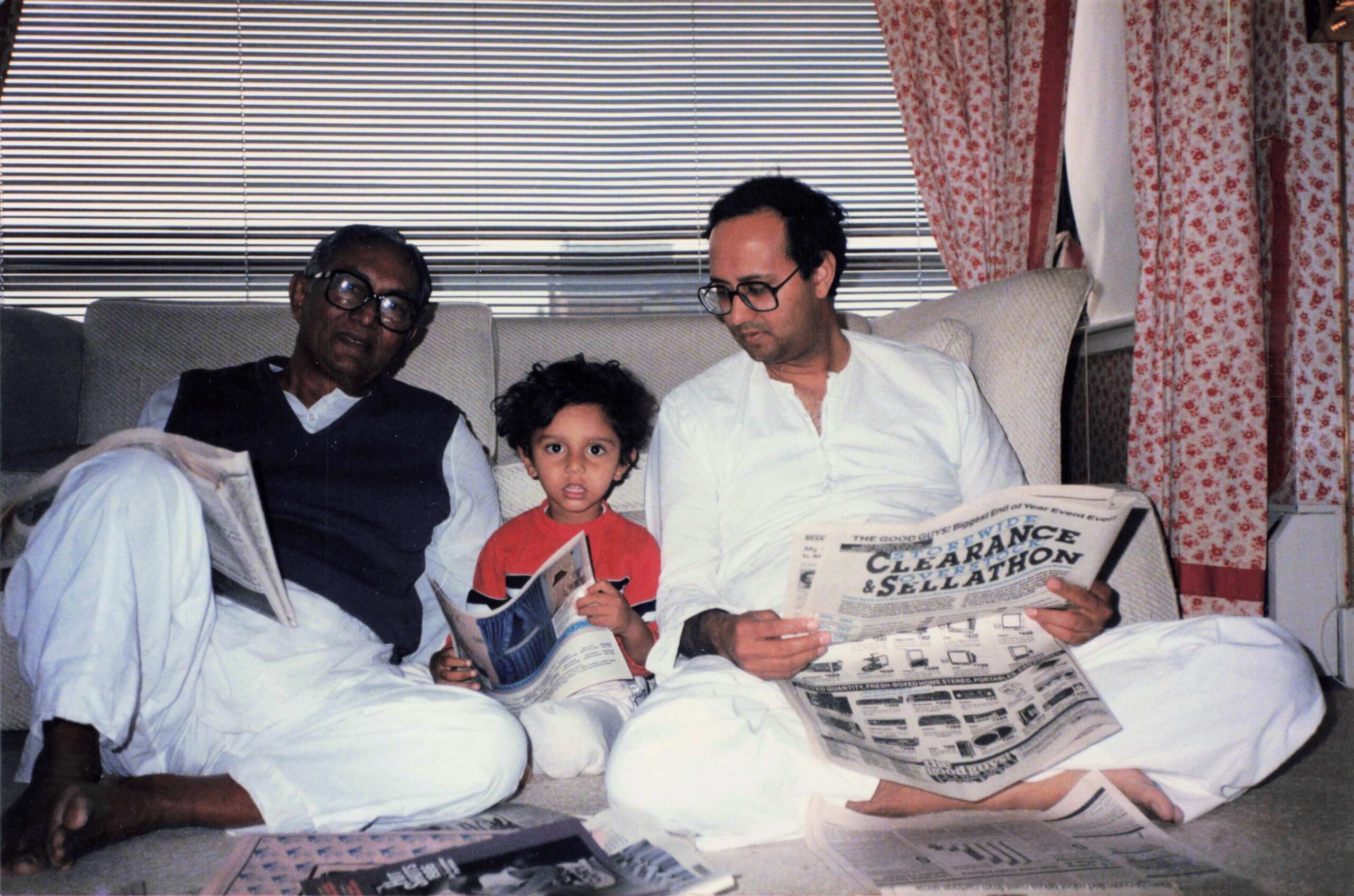

Mehta with his father and grandfather, 1986

Mehta finished college at the London School of Economics (LSE), where due to an administrative error he was assigned to live in student accommodations with four girls—an otherwise nightmarish experience redeemed by the fact that one of his roommates, Jash, became the love of his life, and later his wife and the mother of his three daughters.

After LSE, Mehta took a job as an associate at the investment firm Kayne Anderson, where one day he uncharacteristically had to be physically separated from a partner and sent home after they nearly came to blows over an investment that Mehta, who was six months out of college, thought was shit. The fact that he wasn’t fired—he was promoted, in fact, after wringing an admission from his boss that he was right about the quality of the investment—gave him confidence in his budding value as an investor, and his ability to think for himself.

That continuity between what he calls his “internal and external voice” evolved at Kayne Anderson, but only really took off once he landed the job with D.E. Shaw. “It was the most formative experience for me,” he said of his time in Hong Kong. “It took going there until I felt really alive. It woke me up in a way. At Kayne it was already happening, but I was still part of the system. In Hong Kong, the shackles came off.”

“I didn’t have anything else in Hong Kong. I had no other responsibilities. I had no obligations. I had nobody I needed to see for dinner. I couldn’t watch sports, the time zones were all screwed up. And I didn’t care to go out. I had nothing. And honestly, I turned into someone else.”

“Then when I came back here and started to build Greenoaks with Benny,” he reflected, “that’s when it really crystallized. I knew then my source of joy was going to be this. I didn’t need to complicate it. By now I’ve had enough feedback from the successes and failures of working with founders—and in the last 13 years I think we’ve captured a disproportionate percentage of great founders—that I’m like, ‘No, this is it. This is what my purpose is in life.’”

“There’s something remarkable about Neil that is so unique to the way his brain works compared to anyone else I’ve met,” I was told by a Silicon Valley source intimately familiar with Greenoaks. “Which is that Neil has an extremely high internal locus of control”—meaning the degree to which someone believes he has control over the circumstances of his life. “When you consider that everything in the world was first a thought in someone’s head, that’s an expression of how humans can impact our environment. And Neil is a force in this way. I have mental models of probably a thousand people in my brain, and Neil has the strongest internal locus of control that I’ve ever encountered. I can’t emphasize this enough. He can break reality.”

CAROLYN FONG

Bom Kim, the Founder and CEO of Coupang, contrasted this quality of Mehta’s with most other investors, who will often say to founders with crazy-seeming ideas, “‘Look, I actually think you’re right. But if all the sailboats are moving in one direction, and I’m the only sailboat moving in the other direction, if I’m right, I get promoted; if I’m wrong, I get fired.’ So think about the competitive advantage someone like Neil has when he’s not beholden to that framework. Which takes courage, by the way. So it’s not only the first principles, clear thinking, the conviction-driven thinking that he operates with. It’s also having the guts. I think from Greenoaks’ early days, Neil’s always told LPs, ‘This is who I am. This is how we operate. We don’t diversify. We concentrate, and we drive on X.’”

“Neil’s got an incredible IQ. He’s also got incredible EQ, which wins people,” Kim said. “But there are a lot of people with EQ-IQ combinations. Not that many, it’s still special. But it’s not what makes Neil rare, which is those plus conviction and courage.”

“He tries to kind of shape or bend the world, rather than bending to it.”

Mehta and Benny Peretz started Greenoaks in 2012, in a foul, borrowed backroom office of an insurance broker in San Francisco. “We started with a very clear mission,” Mehta said, “and it hasn’t changed. Find great founders building great businesses, become their single most important resource, work tirelessly to invest in them, and then become the most important partner they have. And do it over the course of decades, not years.”

It turned out that back in 2012, the world was open for business. Mehta and Peretz cold emailed hundreds of people, everyone they could think of that they wanted to meet, and pretty much everyone responded, including Patrick and John Collison, Jack Dorsey, Travis Kalanick, and Joe Lonsdale. Tom Hardy, an early Greenoaks hire, remembers some of the biggest hedge fund and private equity figures in the world gravitating toward Mehta. “It was kind of a game-recognizes-game situation,” Hardy said, “where these people who were objectively much more successful, much further on in their careers, gravitated toward Neil almost more than he did to them. Some of them practically stalked him.”

We’re only focused on two things in life: great business models and great founders. When you find them in the same situation at the same time, we go all in.

–Neil Mehta

Greenoaks’ first official investment was a $3 million secondary transaction in Palantir, which Lonsdale permitted the unknown but promising Mehta on the condition that he got his shit together, which presumably meant moving out of the broker’s office. Other early investments included Flipkart, now the largest ecommerce company in India, and OYO Rooms, another Indian unicorn.

But the investment that put Greenoaks on the map was Coupang, which technically began a couple of years earlier. Mehta came up with the name Greenoaks, in fact, in order to sound legit when he approached Bom Kim, whom he’d met through a friend, to inquire about backing him. Kim was then in the process of dropping out of business school to start the Groupon of South Korea, selling daily deals.

“What’s Greenoaks?” Kim asked. “Well,” said Mehta, “we invest in companies like yours.” “Uh, okay,” Mehta remembers Kim saying.

“I just remember meeting him and thinking to myself, this guy is a genius. He’s clearly going to be the Michael Jordan in this space,” Mehta said. “I knew I wanted to play with him for the rest of his career. The ability for him to articulate what is most jugular, go attack it and solve it, and then demonstrate how he solved it, that feedback loop, you see it once in a generation.”

Today Mehta is the Lead Independent Director of the $45 billion company, and Greenoaks has led five of its eight rounds, investing nearly $1 billion in Coupang across a decade. But while Mehta speaks often of his good fortune to have met Kim so early, the story of how they got to where they are now belies the idea of luck.

At a certain point early on, Kim realized that Coupang wasn’t going to be Korea’s Groupon but a global ecommerce juggernaut. By the time of the company’s Series B, Mehta had essentially bet all of Greenoaks on Coupang, and was de facto involved in the fundraising. Kim and Mehta invited all the biggest Bay Area and New York investment firms to visit the office and meet the team. “It was like an emperor has no clothes moment,” said Mehta. “These are all the most lauded firms I’m supposed to respect, and they’re all asking the wrong questions.”

For example, at the time Coupang had about 8% gross margins, and the firms didn’t like that. “Amazon’s gross margins are 30%,” they said. “How are you going to get to 30%?” What they should have done, Mehta explained, was look at Coupang by category. An ecommerce retailer adds product to its website in stages, and starts out with very unfavorable agreements with its wholesalers and manufacturers, which it then renegotiates over time as it builds scale. Criticizing Coupang’s margins at this juncture missed the whole point, said Mehta, which was that Kim was willing to take significant losses at the start while he built out a Jaw Dropping Customer Experience (JDCE)—which included the best overall delivery experience, and pricing Coupang’s goods to match the lowest prices in the market—understanding that with time, scale, innovation, supply chain optimization, and increasing operational efficiency, momentum in customer adoption would accelerate, and margins would eventually expand.

“Today, it’s a 30% margin business,” said Mehta. “But nobody asked about any of that stuff at the beginning. They came in and they just saw the low margin number and they walked out. They didn’t see it because they wanted the answer to be easy, rather than understanding that to build something great, it takes breaking tradeoffs that might not be obvious at the start. You have to go talk to the people involved in the business, the suppliers, the customers.”

“Back then, you could go up and down apartment buildings to talk to customers about Coupang, and they’d be crying, literally crying, from happiness. I remember watching with Bom as we saw one mother crying because the diapers she ordered were showing up at her door first thing in the morning—which meant she didn’t have to carry these giant boxes back home from the store. She was like, ‘If you took this away from me, I don’t know what I would do. Please don’t take this away from me.’ You can’t see that kind of affinity in a retention curve.”

“We had this huge transition where we had just turned profitable as a third-party marketplace, we were planning to go public,” Kim said. “And it was at this moment where a lot of people could cash out with very, very high IRRs. We were basically right before the final step of going public, and had spent months and months preparing, and I pulled the plug. Because I was convinced that there was this huge opportunity if we made a very big bet, which was to invest in not only a fulfillment network, but also a logistics network from scratch”—a process that included building a cutting-edge warehouse management system, football field-sized warehouses, delivery camps, localized distribution points, custom packaging, etc. “And we had lots of investors, even board members who were very familiar with Amazon. And they said, ‘Amazon couldn’t make that successful, therefore you can’t.’”

“That’s not clear, first principles thinking,” Kim explained. “That’s like saying, well, a bird flaps its wings, therefore an airplane has to have wings that flap, and metal doesn’t flap, therefore you can’t fly. Whereas Neil, who instead of seeking safety, really tried to get to conviction. That meant he spent hours and hours and hours with this kind of voracious hunger to understand the details and new concepts. And as much as we would open up, he was willing to spend time to get to conviction on either a yes or a no. And it hasn’t always been a yes.”

Coupang is also the investment that first gave Greenoaks its enduring reputation for being a founder’s go-to partner in an emergency. The reader may recall that in the fall of 2017, there was a wee chilly moment when the nuclear-armed totalitarian dictator of North Korea used the 14th-century, late-Middle English term ‘dotard’ not once but twice to refer to the President of the United States, himself the commander of 5,000 nuclear warheads and no great paragon of rhetorical restraint. Kim had been in the process of fundraising for months when spooked US investors pushed Korean equities off a cliff. After several rounds of discussions about how to move forward, Mehta and the Greenoaks team flew to South Korea and injected half a billion dollars into Coupang shortly thereafter. That investment returned more than tenfold in a few years.

A lot of them talk about how the secret to being a great investor is leaning in when others lean out, and vice versa. It’s very easy to say, but really terrifying to do in practice.

–Parker Conrad, Rippling

“Nobody else wanted to do it, we were the only ones,” said Mehta. “All of our alpha comes from ignoring the memetic vibes of Silicon Valley and New York and focusing on the fundamentals of a business and the founder. That’s it.”

“It takes a lot of stamina, doing that kind of deep dive, it’s physically grueling,” Kim concluded. “We have a phrase in our company, ‘You’re still on the helicopter’. You need to land the helicopter, get on the ground, you should be on your knees getting dirt in your fingernails. Most people bring the helicopter down from 10,000 feet to 8,000 feet and think they’re diving deep, but they can’t get off the helicopter. Is it because they’re not smart? No. It’s because it takes too long to get to the core of the issue when there’s a lot of ambiguity and too much information.”

“How did Greenoaks become a machine? It’s because Neil gets on the ground, gets dirt in his fingernails. And it’s unpleasant, it’s tiring. It’s physically and mentally grueling. But I’ve seen him get off planes, lock the door, and spend six hours with me or other team members, just going through all the details. How many investors do you think just send due diligence teams to do CYA [cover your ass], versus getting to conviction one way or another? That’s the thing with Neil: one way or another.”

Such virtuosic stories of being early and right, and of making more on a single investment than the returns of most other investors’ entire funds or careers, are legion at Greenoaks—including of having predicted the Silicon Valley Bank run of 2023 in a letter that saved portfolio companies with money there; and of Wiz, the Israeli agentless cloud security company, which Mehta and his partners didn’t know existed until they sussed it while diligencing the company’s competitors—at which point they called the Founder, Assaf Rappaport, talked to him for 30 minutes, dropped the competitors, and a week later led a round at a $1.7 billion valuation when the company was doing only $2 million in revenue. (In March 2025, Google acquired Wiz for $32 billion.)

There was also Rippling, which had hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of customer payroll potentially stuck in SVB as the bank was collapsing. The company’s Founder and CEO, Parker Conrad, called Mehta on that Friday to float the idea of backstopping its customers’ payroll using the company’s balance sheet. “And I sort of said, ‘Look, this only works if you can wire us the money on Monday morning,’” Conrad told me. “So we would need to negotiate the deal, sign the term sheet, and wire the funds by then … And we were like, you have to understand: We’d take this money, and there’s a decent chance we’d send it right out the door to customers to cover payroll. That was a possibility, and it was also not clear how Rippling would be viewed after this. We were talking with Greenoaks about, what if 30% of our customers leave us next month because of this issue? It was entirely possible he was putting money into a sinking business.”

“And Neil was like, ‘Great, we’re in’—right on the phone,” Conrad remembered. “And we signed a term sheet at 9pm Friday night. So this was a $500 million investment round that went from a handshake to a term sheet in 12 hours, on a day when the financial world was melting down … There were no other investors doing that. A lot of them talk about how the secret to being a great investor is leaning in when others lean out, and vice versa. It’s very easy to say, but really terrifying to do in practice.”

CAROLYN FONG

Then there was Carvana. Like the Imagi team, like the Collison brothers and Kim and Rappaport and Conrad, Mehta fell for Ernie Garcia. Garcia founded and built Carvana, the online used car retailer, in the private market without taking a dollar of venture capital, and not for lack of trying. When Garcia went out to Silicon Valley to raise money for his company, nobody would give it to him.

Carvana went public just as Greenoaks had started to get going. The price was high, but Carvana was the acme of the JDCE, which by that point was becoming the Greenoaks mantra. “We didn’t know Ernie yet,” said Mehta. “But I knew it was a Jaw Dropping Customer Experience for anyone looking to buy or sell a used car, that it was irresponsible for anyone looking to do that to go anywhere besides Carvana. It was just clearly what Amazon did for books.”

As the pandemic unfolded, Carvana’s price collapsed, so naturally Mehta wanted to buy. Several Greenoaks investors went ballistic, figuring that once COVID eased, the era of buying used cars online would be over. “This is a terrible trade, Neil, don’t invest, this company is going to go bankrupt,” that kind of thing. And they were right, in a way: Garcia did a $2.2 billion acquisition of ADESA, a physical auction business, but then the cycle turned, the country went from low to higher rates, growth slowed, people stopped buying cars, and Carvana underwent an infamous peak-to-trough drop.

Not many companies go from $60 billion to less than $1 billion in market cap unless they’re frauds, Mehta pointed out, and that’s the headline the media ran with. Every news story in those days was about Carvana approaching bankruptcy, about how Garcia had a secret deal with debt holders, that he was going to inject capital and wipe out the equity. Yet once the stock price dipped below $20, Mehta and Greenoaks got serious.

“There was an insane amount of noise,” Mehta said. “So we just rolled up our sleeves and tried to understand what was happening from first principles. We spent a lot of time talking to customers of the product, a lot of time talking to competitors of the company, a lot of time understanding the cost structure of the business—an inordinate amount of time understanding the capital structure of the business. And we started buying stock.”

It was unusual for a mostly private investment firm to buy stock, especially as Carvana went from the $20s down to the $10s and eventually to $5. By that point Greenoaks had returned something like $11 billion to investors, but the phones were still ringing off the hook with LPs saying things like, “What the hell do you know about Carvana? You don’t know anything about Carvana! How do you know more than Apollo [the lenders]?” But Greenoaks kept buying more stock until it bought about 4% of the company, which had its own recurring ‘suicide watch’ features in the business press, counting down the clock to bankruptcy.

“It was hard on all of us,” Mehta said. “If you haven’t been through something like that, which many of our younger colleagues hadn’t, it can be demoralizing. Terrifying. You start asking yourself, what’s the point of doing all of this work? We’re screwed.”

“In other times, we’ve had differentiated insight and it’s been obvious internally that we had it. That’s when you see something in the numbers that nobody else sees, and we believe we’re right and everybody else is wrong. That was happening with Carvana, too. But for some reason, because it was a public company, seeing a price you buy out go down by half the next day, and you’ve put a lot of your fund into it, and then immediately lose money on it, there’s some psychological effect. It was easy to worry about our LPs firing us.”

“But the thing is, we’re not playing the game of, ‘Is the stock going to go up or down tomorrow?’ The game we’re playing is, ‘Will this company delight consumers in the tens of millions over the fullness of time, produce real gross profit per unit, and be a free cash flow machine run by a great founder that could compound for the next 10 years? Is Ernie building a generational company that’s going to be a meaningful part of the S&P 500 over time, or isn’t he?’”

“So there was a moment where I was like, look, maybe we just need to go understand this. We have to stop talking to Ernie on Zoom; we have to go spend time with him.”

Mehta flew out to Arizona to see Garcia alone, and spent four or five hours with him over dinner. It was at the peak of rumors that Garcia had a secret debt deal with Apollo and was waiting to bankrupt the company. Mehta remembers Garcia with his soul between his teeth, “not because of what was happening, or because of the character assassination in the headlines,” he said, “but because of how he had to manage his employees. He was going through a way worse version of what I was going through with some of our own team members who were anti-Carvana. Ernie was having to explain to people that worked for him that he wasn’t a criminal, including spouses worried about their families who had until recently been so proud to work at this extremely high-performing company. He had tears in his eyes talking about how he had to explain to the families of people that worked for him that Carvana was going to be okay.”

“I remember thinking, ‘Either he’s a psychopath, or he’s going to be just fine.’ Because you can’t manufacture that level of empathy. So we just talked about the company, we talked about the strategy, how he was going to cut costs, how he was going to manage through this. It was all rational. It all made sense.”

Mehta acknowledged that Carvana was a very good investment for Greenoaks—the stock it holds is currently worth around $1.2 billion—but insisted he’s proudest of the other rewards. “First, I’m proud of the differential insight we had around the founder and the business. Ernie and his team did all the hard work, but it was rewarding being in their corner. Second, there are lots of firms that would have sold their investment the moment they were proven right about the company staving off bankruptcy. I’m proud that we were able to see through some of the worst times to understand how the company could grow into a category leader and the cognitive referent in the industry. So it’s not only getting the bankruptcy trade right and being mathematically sound—and being foundationally better than other people at the underwriting. It’s also about allowing yourself to be partners to the company as it goes and attacks something big. What I’m really proud of is that we’re the kind of firm that could do both.”

“I went to dinner with one of the most successful Silicon Valley VCs right after we had purchased the stock,” Mehta remembered, “and he was like, ‘Are you fucking insane? You’re playing the lotto. You don’t need to look at the numbers, just look at the stock price. It’s over.’ And I realized then that he didn’t actually know any of the numbers. He had just read the articles.”

Mehta confesses to some big stumbles over the first 13 years of Greenoaks, whose raison d’être, as he put it, is to capture “the very small number of the world’s founders who are going to produce a significant proportion of the value that humans enjoy.” When asked which founders he’s missed, Mehta responded, without missing a beat, “Tony Xu, Brian Armstrong, David Vélez … but no one bigger than Elon Musk.”

Mehta and Peretz had known about SpaceX early on, but some of their industry mentors warned them away from Musk. “He fires people quickly, he micromanages people like crazy, he disappears for large swaths of time, comes back in and changes everything,” Mehta remembers being told. “And we were like, well, I guess we can’t back him then.”

“We didn’t do the primary work ourselves,” Mehta ruminated, venting his spleen. “We outsourced that work. I cost our investors billions of dollars because of that. We later became small investors [in SpaceX], but I’ve had to look our investors in the eye and tell them we’ve lost them tens of billions of dollars because of the mistake we made as a firm on that. And I told myself then: I’ll never not do the work myself again.”

We can understand from the outside-in better than almost anybody else on Earth. There’s no need to explain the 101 or go through remedial background. For a founder, that makes a first meeting with us feel like a fourth or fifth.

–Neil Mehta

The machine Greenoaks has fine-tuned ever since is purpose-built to correct for that early error. “If there have been 100 billion people that have lived on Earth, and between 10,000 to 100,000 who have affected the technological progress of humankind,” he explained, “our job is to find the few hundred living now that could join the pantheon of great humans that have driven humanity forward. So first, we’re focused squarely on that. Second, where we’re differentially great partners, where we generate alpha, is by having a deep understanding of the business model.”

The process looks something like this: Greenoaks selects for people who believe that it’s really hard in the world of capitalism—which is filled with “me-too products swimming in a river of beta,” in Mehta’s phrase—to build something that delights human beings at a differential rate. The world therefore moves forward only through the products and companies built by generational founders who break tradeoffs and build competitive moats by creating a Jaw Dropping Customer Experience, which “usually starts with doing something perceived to be impossible, either technically or operationally, that gives competitors nightmares. Everything else is just a shell game,” Mehta believes.

Each year, Greenoaks identifies about 10–15 people who might be like this, and to whom the firm could be a uniquely close partner. Before any meetings, they set about preparing. “I don’t mean go on the website and use the product a little bit,” Mehta said. “We’ll talk to their customers, examine exactly what competitors are doing, understand the product in a granular way, study the underlying technology and how it’s evolving. There’s a series of things we’re testing for, depending on the company. We can understand from the outside-in better than almost anybody else on Earth. There’s no need to explain the 101 or go through remedial background. For a founder, that makes a first meeting with us feel like a fourth or fifth.”

Then there is the pace. “I think what we’ve become much better at,” he said, “is increasing the speed and velocity in our information asymmetry—getting much more information and being able to generate differential insight that matters to long-term enterprise value, and putting those three things together with a small team and building a flywheel for doing it over and over again every day. That’s been a sea change in the last couple of years.”

After preparing, Mehta and Peretz spend several hours discussing each company. While talking, they’ll call various partners, friends, and colleagues to join the conversation for an hour or two. Then they go home, put their kids to bed, and talk again on the phone, often from 9pm until 1am, nearly every night. The overwhelming majority of these conversations end in a decision not to pursue. “And then we just drop it and let go,” said Mehta. “Do you know how infuriating that would be to most people? But we love it. So we ‘wasted’ four hours. Who cares? We’re trying to find someone we want to partner with for decades who’s going to create art that changes the world. They’re painting their painting, and we want to find them. It has to be perfect.”

When it’s a yes, Greenoaks does not lard the process with advisors, large investment committees, or long, asynchronous diligence sessions. Mehta personally leads every first meeting with a founder, typically on site at the company rather than in the Greenoaks offices. “I want to be very explicit about this,” Peretz told me. “Neil joins every single investment process from the very first meeting with the founder.”

“If I walk out of a meeting and I don’t want to spend time on something that has five of the best firms in the world on the cap table,” Mehta said, “I feel totally comfortable killing it. I won’t lose a wink of sleep. And the opposite is true, too. If I find something incredibly interesting, but it’s a little crazy and a little out there, which a lot of the things we get excited about are, I’m totally comfortable pursuing an investment of $500 million or more in the next 36 hours. And I can marshal the resources and feel comfortable that if I’m wrong, we’ll live to fight another day, as long as we did the work.”

Monday mornings are for the Greenoaks pipeline meeting, and for spending time as a team talking about what they want to prosecute, what they want to drop, and how they want to organize time. Peretz in particular plays the role of extending the firm’s time horizon, according to Mehta. “Sometimes when things are moving really fast and you’re in the fog of war, you find yourself trying to make decisions that are optimal in the short term because you can only see that corner,” he said, with the gooey eyes he gets when discussing his partner. “Benny has an astonishing ability to step back and remind everyone, including me, what we’re trying to optimize for over the long term.” On Monday afternoons, Mehta occupies the ‘War Room’ (it’s just a room that connects Mehta and Peretz’s offices), where he talks to people about companies until around 8pm, at which point the team goes to dinner—the only night of the week he doesn’t see his daughters.

Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays are for calls and company meetings. Fridays are for “deep work,” which usually means Mehta sitting alone in an office writing about a company or studying it, or reading through a pile of papers on Bitcoin, childhood gaming apps, or AI labs. On his desk, Mehta also keeps a list of the S&P 500, “and I just try to figure out what companies are not on that list today that will be on that list tomorrow, and how do I become the single most important partner they have?”

CAROLYN FONG

“This is controversial,” Mehta replied, when asked if the Greenoaks machine has identified an ideal type, “but I do believe there’s an archetype for a great founder. And I think that once you see it and learn it, it’s a repeatable process. We’re looking for remarkable intellect, extreme focus, an obsession with the customer, unreasonable determination, especially in the face of adversity, clear and credible ambition, and usually a bit of divergence—people who don’t feel the need to be liked by everybody.”

“A lot of people in our industry say they want these things, but we try to be more systematic and rigorous than anyone else about how we look for it. Every business is the cumulation of a million small decisions made by the founder, and when you look really closely at a company, it’s kind of a prism that shows you much more about them than any conversation does on its own. It’s like, Buffett says you could sell 20 IQ points and still be great; our process would probably allow you to sell more than that. It’s not that complicated. It’s the discipline of only looking for those types of businesses and those types of founders. There is no secret sauce. It’s just the consistency of doing this again and again across thousands of companies.”

When told that as a writer, and not an investor or founder, I find it hard to square the brute force of Greenoaks’ research process with his analogy to “perusing an art market, looking for the future Kerry James Marshall, or David Hockney, or Rembrandt,” Mehta replied:

“If anyone sits with Benny and me for a day, I think the thing they’re probably most surprised by is how much we talk about beauty. We love the analytical work, we love spending time on a P&L. But the whole point of that kind of work is to help us find the greatest founders building the most beautiful businesses that truly delight their customers. We love beautiful relationships, we care about beauty in the world … And understanding a founder, deeply understanding a business, that’s just the process of discovering beauty. That’s why we invest in the companies we invest in.”

Which brings us back to Ilya Sutskever, and reports that Greenoaks may be investing more than $500 million in Safe Superintelligence.

Although neither Greenoaks nor SSI have acknowledged the story, and Mehta did not respond to requests for comment from Colossus Review, it is worth a modest attempt at speculation, as the 40-year-old Mehta enters what he hopes will be the beginning of Greenoaks’ prime.

The first thing to note is that Greenoaks has remained conspicuously removed from the $1 trillion stampede of investment into the companies chasing artificial general intelligence (AGI) since the release of ChatGPT at the end of 2022. Greenoaks is invested in Scale AI and Databricks, but has been only a small investor in OpenAI, and has not invested in Anthropic, Cohere, xAI, Mistral, or any of the other foundation model companies.

What Mehta was willing to discuss is why Greenoaks has largely stayed out of the model war, in which each player insists, almost daily, that AGI is around the corner. “They may evolve to become great businesses, like ChatGPT is, but in their first incarnation they are all kind of bad business models,” he said. “Huge capital investments up front to create this asset, the asset is worth some amount of money, which then depreciates over the course of 12 months, so you have to reinvest again 12 months later. It’s like the airline business in the 1980s; you invest in the best fleet, but then 12 months later the other airline has the newer models, and you don’t pay back the cost of your initial capital investment because the unit economics don’t work. That’s the AI model companies. They have no competitive advantage. If you create a brand like ChatGPT, or if you achieve so much scale that you capture all the capital and no one else can compete, maybe you can escape that. But it’s not obvious that everyone does.”

Sources sympathetic to Mehta’s viewpoint who requested anonymity explained that the business limitations are inherent in the technological ones. In their telling, the model companies are all doing more or less the same thing, which is scaling transformer models: building massive data centers, using ever more GPUs, buying huge amounts of label data to unhobble the models, and then training the models with more compute and more data, over and over and over again. In a word, they’re merely scaling the horsepower of transformer models, rather than innovating on the underlying model. Insofar as this is a fair characterization, it would explain Mehta’s skepticism of the potential for returns, competitive advantage, or anything else of classical business interest, which powers the Greenoaks machine.

It might also go some way to answering the question posed by Dwarkesh Patel in his August 2023 interview of Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei, which did not appear to receive a satisfactory answer. Patel asked why the foundation models, which have memorized the entire corpus of human knowledge, and can easily reference it within microseconds, have not been able to make a single new connection that has led to a discovery—whereas even a moderately intelligent person with that much knowledge memorized could make a connection that leads to, for example, a medical cure.

The answer, or part of it, is that the foundation models are essentially colossal word replication and regurgitation machines. This technology is in fact likely good enough to reach AGI, which could lead to trillions of dollars in productivity gains over the course of time—no small achievement, to put it mildly. But they are unlikely to ever match or exceed the possibilities of human cognition. For that, one would need to build a model that could learn a lot from very limited amounts of data, and generalize from first principles. Such is the threshold for superintelligence, which could make the kinds of connections and discoveries that would elude AGI.

What Sutskever’s claim to have found a “different mountain to climb” suggests, and what the sextupling of SSI’s valuation in a little over five months appears to imply, is that the company’s progress toward superintelligence is going quite well. At the very least, if the reports of Greenoaks’ investment are accurate, one could reasonably infer that Mehta was shown something that met every one of Greenoaks’ criteria described above—which the foundation model companies largely have not. “We’re simple people,” Mehta told me in a different context, when discussing Parker Conrad and Rippling, to which he wrote a $500 million check overnight during the SVB crisis. “We’re only focused on two things in life: great business models and great founders. When you find them in the same situation at the same time, we go all in.”

Like Conrad, like Musk—like the archetype of a founder, in other words, that Mehta says is repeatable, and which Greenoaks pursues with unusual ferocity, and is anxious never to miss out on again—Sutskever underwent a painful and controversial exit from his previous venture, and now leads a company he’s said is “very personally meaningful to him.” There is also the matter of Sutskever’s raw intellectual firepower. He authored the 2012 AlexNet paper, which catalyzed the modern AI boom, developed Recurrent Neural Networks and Sequence-to-Sequence Models at Google Brain, co-founded OpenAI, and served as Chief Scientist for GPT 1-4 and the company’s reasoning models and alignment research. His murky, convoluted, and protracted departure from OpenAI, moreover, appeared to stem from an authentic intellectual break with CEO Sam Altman, over which Sutskever was prepared to cut his umbilical connection to the company he co-founded, which at the time was soaring past a valuation of $150 billion. Taken together, Sutskever evidently possesses the type of N of 1 conviction and sedulousness that Mehta believes makes “every great founder look approximately the same.”

It is likewise reasonable to deduce the nature, if reports are accurate, of Sutskever’s interest in Mehta. Given the total secrecy in which SSI operates, and will continue to operate until the very day, it says, it unleashes superintelligence upon the world, it would likely want a lead investor who does not employ a privy council of investment committees; who does not delegate research to subordinates; who is known for hiding his plumage; who has the implicit trust of his LPs; who is among the largest LPs in his own funds; who is highly concentrated; who pooh-poohs “venture math” and “rivers of beta”; whose firm, on principle, has never invested in China; who can understand a company from the outside in better than anyone else; whose first meeting often feels to the founder like the fourth or fifth; who is “the epitome of non-zero-sum thinking,” a combination of “warm, jubilant energy and high ambition,” and “the same dude across the board,” as Figma founder Dylan Field put it; who has “lost his taste” for any other type of work; and who—once he believes he’s understood a business better than anyone else—can write a $500 million check on the spot.

Perhaps it would also be of interest to Sutskever, who may or may not be within reach of a product that could change the species, that Mehta would view him as an artist; as a painter painting his life’s work; as a creator of beauty and innovations that multiply the supply of beauty in the world; as one of the 10,000 people who’ve ever breathed air who could affect the progress of humankind; as someone that Mehta would get off the helicopter for, onto the ground, with dirt in his fingernails, as his closest partner not for years but for decades, to build a Jaw Dropping Customer Experience that will delight human beings in the millions or billions, and produce a free cash flow machine that compounds ad infinitum.

In contemplating the possibility of such a partnership, one is reminded of Neil Mehta as a tiny figure in a vast and alien place, standing beneath an enormous structure towering above him, staring into the gorge of the future—and smiling.

Jeremy Stern is the editor-in-chief of Colossus.

Click here to subscribe to print for your office or home.